It was a lovely spring day in 2000, around May, I think, that I decided to fire up the jeep and drive to work in it for a change. The jeep (I don’t have pictures, unfortunately) was a 1976 CJ-5 with a V-8 engine, a moderate lift, big tires, and steel I-beam front and rear bumpers. I bought it for $2500 off Norm L., who had owned it for a decade or so and wanted to get rid of it because he never drove it. It was a great thing to pull stumps with, or put the wheel locks in, and go 4x4ing around the yard in when the snow got deep. Since it had no top, it just filled with snow in the winter, but you could climb in, sit in the snow, and start right up.

It was around 6:00pm that I headed home, so I was in my neighborhood around 6:30pm. I always took back roads on the way to my place, and the ground was rolling fields, mostly, with trees and banks. I never drove the jeep particularly fast, so I was doodling along at about 35 when I had the trolley problem.

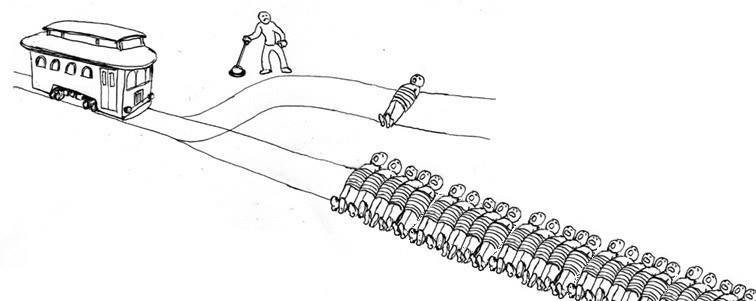

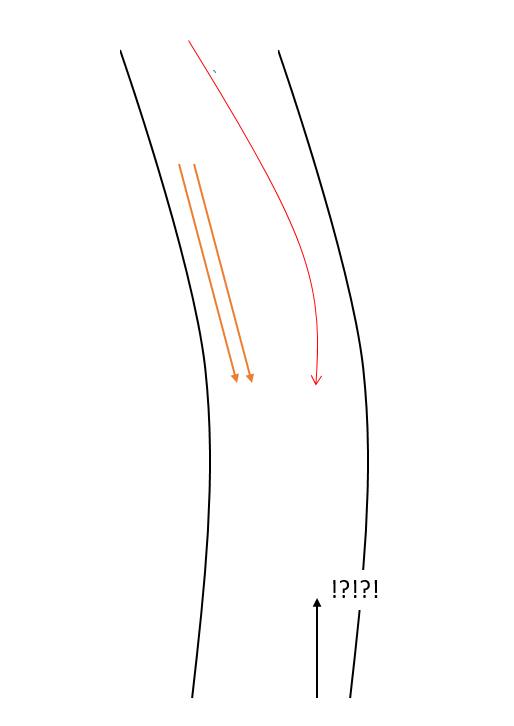

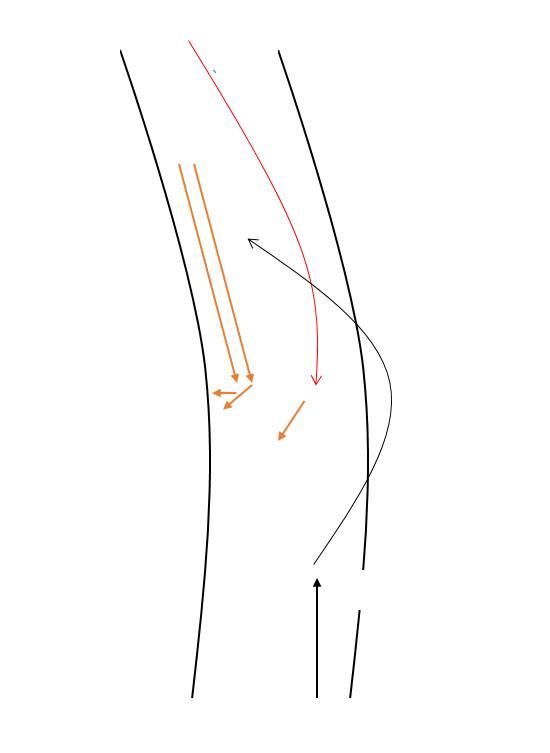

Coming up over a small incline, I discovered there were two bicyclists riding side-by-side in the opposite lane, and a Lexus something-or-other was passing them. The road in front of me was completely filled with stuff, coming at me at about the same speed as I was going.

That’s the trolley car scenario, sort of. A consequentialist philosopher would expect you to be able to coolly and rationally make the best decision, taking into account the possible outcomes and pros and cons.

That’s the trolley car scenario, sort of. A consequentialist philosopher would expect you to be able to coolly and rationally make the best decision, taking into account the possible outcomes and pros and cons.

And that’s why I hate trolleyology: even the classical formulation of the trolley problem assumes you haven’t got a whole lot of time to think about it – in fact the problem is contradictory because it assumes you’ve got time to think about the problem but not time to think in the scenario. You can’t get an accurate perception of a person’s response – reflexive or moral – unless they’ve got 1/10 of a second to answer. Or less. It is a completely phony situation, so we should assume that questioning people about how they’d behave is going to produce a completely phony set of answers.

If I’d had enough time to be thinking about it, I’d have been wearing my seat belt – in which case I’d probably be dead or mangled.

If I’d had enough time to be thinking about it, I’d have been wearing my seat belt – in which case I’d probably be dead or mangled.

Here’s another annoying thing about the trolley problem: it assumes everyone else is completely passive. What happened in my trolley situation was the guy in the Lexus stood on his brakes, the bicyclists swerved and crashed into eachother, heading for the bank on the side of the road. I swerved right and braked, aiming for the empty field on the right hand side. Then, the front bumper of my jeep buried itself in the dirt of the bank on the side of the road (I had hoped the jeep would go up it) and spun violently sideways, then flipped on its side, sliding right past the Lexus.

As the Jeep flipped, suddenly I was in a huge cloud of dust and I remember seeing my briefcase (a nice aluminum Halliburton Zero) zip through the passenger door (the jeep had the doors off for reasons of cool), I bounced off the steering wheel, and when the jeep started to roll I put my foot on the roll cage (which was now to my left) and jumped into the passenger side, grabbing the opposite roll cage and hanging on like it was pull up bar, which it kind of was. Everything stopped moving and got really quiet, then I came storming out of the cloud of dust surrounding my jeep and yelled at the guy in the Lexus, “THAT IS WHY YOU ARE NOT SUPPOSED TO PASS ON A HILL!”

I had a small abrasion on the side of my left elbow that went down to some tendony-looking stuff, and the sleeve of my hoodie was completely shredded and covered with blood. My briefcase was embedded in the bank, and I went and picked it up and dug my cellphone out and called my mechanic to come with the flatbed (I was not thinking clearly). Meanwhile the bicyclists called the police. The guy in the Lexus came over and started babbling something about “at least you weren’t hurt.”

I had a small abrasion on the side of my left elbow that went down to some tendony-looking stuff, and the sleeve of my hoodie was completely shredded and covered with blood. My briefcase was embedded in the bank, and I went and picked it up and dug my cellphone out and called my mechanic to come with the flatbed (I was not thinking clearly). Meanwhile the bicyclists called the police. The guy in the Lexus came over and started babbling something about “at least you weren’t hurt.”

Somehow I had managed to, by sheer luck combined with a consequence of my maneuver, bounce around the Lexus and nobody hit anybody.

I’m pretty sure that if I’d had time to sit in an armchair and think about it, I would have chosen to ram the Lexus, which might have killed somebody (I-beam bumpers, remember? me, no seatbelt, remember?)

Cops came and wrote up a report and I was so happy to just be in one piece that I declined to press charges against the guy in the Lexus, who left. My mechanic showed up with a flatbed and winched the jeep up, and I just walked home. It was 5 miles and my day was over. I was glad to be alive and my jeep was tough, I’d have the mechanic replace that side mirror and check it out and it’d be fine.

Trolley car problems are real, but I don’t believe we think about them; sometimes you don’t have time to be a consequentialist. To me, that amounts to a refutation of consequentialism, right there: you cannot know what’s going to happen to you anyway – you’re making your choices based on an imaginary model of how things may or may not work out, but you have no idea what is going to actually happen. I won’t say “my instinct was to aim for the field” because I don’t think we have driving instincts. My aiming for the field was probably a reflex from decades of bicycling and motorcycling: aim for where the awful stuff isn’t. If the bumper hadn’t caught on the berm I probably would have flown up over the bank and it would have been a whole lot worse.

Part of my nihilism comes from having, several times, had the experience where physics just takes over and my will is completely irrelevant. Intentionality, free will, whatever – all that stuff goes out the window once momentum (or combustion, or cancer, or whatever) has decided to interrupt the happy little imaginary scenario in which you’re in control of your life.

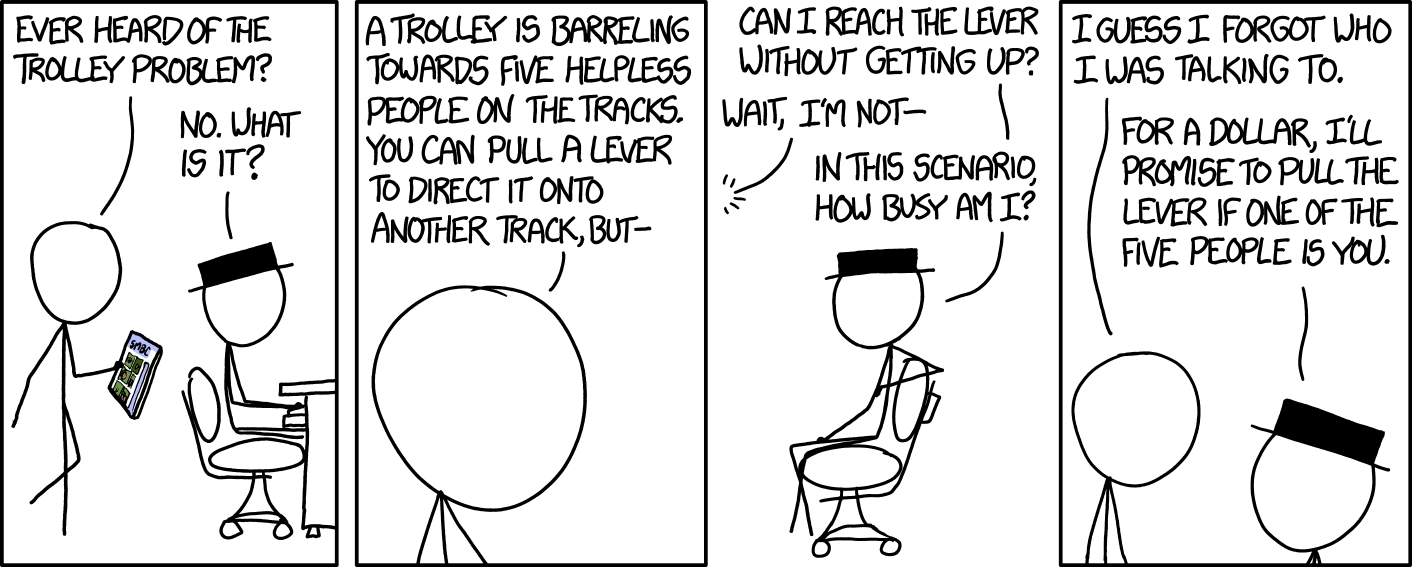

[source of course]

A week or so later, I went to the mechanic to pester him about the jeep and he said “come around back let me show you something.” My jeep was parked there and 3 of the wheels were on the ground, and the other was about 4″ off the pavement. Apparently the wrenching impact from the bumper hitting torqued the frame so hard it bent badly. So that was the end of my jeep. Back to consequentialism: if I had realized that I’d totalled my jeep in order to get around the guy in the Lexus, I’d have at least stuck him for the bill for the jeep.

A few years after that, I spectacularly rolled my Honda Del Sol, and lucked out again. That time, the only injury I suffered was a piece of glass from the windshield stuck in the same exact spot where my elbow hit the road in the jeep incident. I don’t even see any trace of a mark anymore. The “big Norwegian fisher-guy” body genomic options-package I was born with is pretty solid and comes with optional mighty healing.

Your [source of course] is not a link. As a result, how on Earth is anyone ever supposed to know where you got that Randall Munroe drawing with Blackhat and Cueball?

@

That’s one thing that baffles me about the American justice system. I’m pretty sure the onus isn’t on the victim to initiate prosecution proceedings in countries that still practice post-British common law.

No, it isn’t – in fact, the state may well choose to prosecute even if the victim doesn’t want to. There have been a number of cases involving stings against BDSM practitioners where people have been charged with assault over entirely consensual activities.

The time factor is one big problem with trolleyology. The other major problem is that, in real life, the options and the outcomes are never so clearly defined – instead of one trolley, two tracks with known numbers of people who aren’t moving, and one lever, you are normally faced with a complex network of tracks (only part of which you can actually see) with an unknown number of trolleys on them and unknown numbers of people wandering across them, and a large bank of unlabelled levers which many other people are also yanking on more-or-less at random.

The fundamental problem with consequentialism is that it’s extremely difficult to know what the consequences of any given action are, even after the fact. But you have to make choices anyway…

In this scenario, who did each of the six other people vote for?

That’s sort of a cheat. Many real trolley problems aren’t done under tight time constraints. In fact, I’d argue that if there is a time constraint tight enough you can’t make a reasoned decision, then it’s not really a trolley problem; the trolley problem is intended to be a moral dilemma of sorts, so it presumes you have the time to choose your decision rather than going with whatever your reflexes can do quickly.

Johnny Vector@#1:

Thanks – good catch!

I don’t want anyone to think I’m trying to pass Randall’s work off as mine! That’d be quite a plagiarism fail.

Shiv@#2:

That’s one thing that baffles me about the American justice system. I’m pretty sure the onus isn’t on the victim to initiate prosecution proceedings in countries that still practice post-British common law

Traffic laws are one of those “state’s rights” issues, so it’s semi-random. In Maryland, for example, you’re always at fault if you rear-end anyone (even if they decided to just stand on the brakes unexpectedly) In Pennsylvania, they don’t try to assign fault for anything that’s not a crime – giving cops a lot of leeway. It’s a mess.

We have the best justice system money can buy!

Jessie Harban@#5:

That’s sort of a cheat. Many real trolley problems aren’t done under tight time constraints. In fact, I’d argue that if there is a time constraint tight enough you can’t make a reasoned decision, then it’s not really a trolley problem; the trolley problem is intended to be a moral dilemma of sorts, so it presumes you have the time to choose your decision rather than going with whatever your reflexes can do quickly.

Yeah, but if someone gives me the classical trolley problem, why can’t I answer, “hey, if you’re giving me 2 minutes to think about it, that’s enough time for me to switch the trolley to the left side and run down and cut the ropes and rescue the damsels and be a heeeeero!”

My reason for telling this story (other than a good glass of Merlot with my thai dinner…) was that trolley problems are not credible because they are fictionalized constructs, so we’re able to lie with impunity about what we’d do. I see no reason to believe anyone’s answer to a trolley problem because of its abstraction. The flip/downside is that the other option is to measure how people actually behave in actual situations. My situation that day was a close to a real-life trolley problem as I want to ever get, and I acted with no strategic or moral thought. (Although someone could argue I was following my own internal ethics by choosing an option that placed me mostly at risk, to protect the others on the road)

And the last point, of course, is “it’s all random” so I got to take a poke at consequentialism.

Pierce R. Butler:

In this scenario, who did each of the six other people vote for?

There was yuge voter fraud. 3 million!

@Marcus Ranum

I’m not appreciating this hostile environment. I’m going to summon the fascist SJW cultural marxists to no platform you.

/extreme sarcasm

Similar to Pierce Butler

Do we know anything about about the people? There are a lot of people I’d let die to save, say, Linus Torvalds.

An excellent critique of moral philosophy. I eagerly await your critique of quantum physics where you tell us that the Schrodinger’s cat scenario is useless because it’s hard to seal an unwilling cat inside a box.

(This post is written with snark, but it’s not intended maliciously, I promise.)

colinday@#11:

Do we know anything about about the people? There are a lot of people I’d let die to save, say, Linus Torvalds.

When something happens fast, we don’t know. If you’d been sitting next to me and screamed, “That’s Linus!” I wouldn’t have had time to process it and do anything different. So, I acted with an immediate model of consequence but I certainly wasn’t able to make any more complicated long-term judgement, like consequentialists like to think we can do.

I will say for the record, I attended the 1st USENIX C++ symposium in Denver CO (I was a cfront 1.0 victim!) and Andy Koenig and I were crossing the street, deep in conversation with Bjarne Stroustrup, who stepped in front of a bus. I pulled him back by the collar of his jacket just in time. Again, I did it completely without thinking. If I had a better understanding of the long-term consequences of C++’ success, I…. ah, I still would have pulled him back. But maybe I’d have extracted a promise from him to propagate variable typing down at link-time so that overloading would be based on the parameters passed into a function, not on syntax. But, I digress.

I think you’re totally missing the point with Trolleyology, or whatever it is.

I briefly was enrolled in a Philosophy degree, and trolley questions came up. I state that not to claim expertise, I have none. :)

The point of the thought experiment wasn’t to judge how’d you’d act in such a situation, it was to justify your proposed response to a situation.

For example, there’s an evil dude on one line and 6 kittens on the other, you have to decide who dies. You choose evil dude, how do you justify that? Consequentialism? Deontology? Natural Law? Justify? What’s that, I just do what’s right! And so on.

Hopefully it would make you think deeper about second order ethics questions and ethics in general.

Oh, and why wouldn’t you have got Stroustrup to have syntactic sugar like properties, a la c#? What a waste of an opportunity? :)

@Ranum, 8

Because the point of the trolley problem is to illustrate a dilemma: To what extent is it acceptable to inflict harm on a nonconsenting third party in order to achieve a greater good outcome overall?

The example with the trolley is just an analogy to illustrate the problem. Objecting to pieces of the analogy doesn’t answer the underlying problem.

Trolley problems come up in the real world and we are expected to make decisions. That some people might lie about what they’d do in hypothetical scenarios doesn’t change the underlying facts. Trolley problems happen and any moral system that can’t at least offer a guide to reasoning through them is fatally flawed.

Except that the whole point of morality is to provide a guide for how we should act. How people actually act is irrelevant unless you want to argue morality itself is meaningless.

Except if I’m reading it correctly, your scenario wasn’t actually a trolley problem and had nothing to do with the trolley problem.

An essential aspect of the trolley problem is that the cost of the lesser evil is borne by a third party— the dilemma is the extent to which it is justified to harm someone else in the name of the lesser evi/greater good outcome overall. In your case, there wasn’t any third party you were inflicting the costs on.

Another essential aspect is that it’s a moral choice. Split-second decisions that come down to reflex really aren’t the domain of morality; since you don’t have much control, let alone time to reason, it’s kind of meaningless to evaluate it in terms of the choices you should have made.

Mmmm.

Best as I can tell, trolley problems outside the “spherical cow” formulation aren’t true trolley problems.

Anyway.

IRL, nobody is disputing that the answer is “it depends”.

And it kinda meta-depends on the concepts of lives being fungible, presumably they being all strangers.

—

Me, I’d value my wife over some strangers. Fact.

(Minimise suffering, with weighing. Somewhat subjective, but hey)

Brian English:

Given the appropriate premises, any proposed response can be justified.

Arguably, the point may be to see whether the ethical reasoning towards the conclusion is valid given the (meta-ethical) premises and the proposition at hand.

Yes.

Jessie Harban:

Such a simplistic synopsis!

How is it not just as important towards the same goal to prevent harm on a nonconsenting third party.

(As Catholicism has it, there are sins of commission, and sins of omission. Something to be grokked)

—

Ahem.

Trolley problems are definitionally set up as a dilemma (action xor inaction), as you yourself have noted — a no-win scenario. One must sin either by commission or by omission, but one must sin.

(“Kobayashi Maru”)

In the real world, dilemmas of such consequence are hardly to be expected. And they’d have antecedent causes which themselves would be the result of moral conundrums.

(In the real world, there are no spherical cows)

#13

@Marcus Ranum

I was thinking more of the case where you have time to think, as reflex actions are outside the purview of ethics. But thanks for saving Stroustrup.

#13

@Marcus Ranum

I will second (third? fourth?) thanking you for saving Bjarne Stroustrup. I know that C++ is an absolute bastard for compiler writers but I love the language, it is my favorite compiled language.

As for trolleyology, I think I agree that in situation where you are dependent on reflex, there is no time for morality, you start to respond, without thinking, and then physics will take over. I sort of get what some people are saying that the point of the trolley problem is the justification of your choice, but I feel like if anything even a little similar happened IRL, where I had the time to think long and hard, I would probably spend that time thinking up a way to force a third option. Maybe jam the lever in such a way that the track split mechanism goes awry and the trolly jumps the tracks?

Interestingly, what they would actually do in a real situation can change depending on their prior experience. Such as deliberated thinking, training, and so on.

Wait, you think what and what?

Oh… that’s some Plans level stuff right there :(

Maybe you’ve got issues, like those chrisitans who believe they were saved by jesus from their suicidal thoughts. Bit of a conversation stopper, usually.

Brian Pansky@#21:

Wait, you think what and what?

Consequentialism is basing your ethical system on considering the consequences of your actions. If you’re not given time to consider the consequences, then you’d have had to pre-consider all options, or you’re going to act ‘instinctively’ – unless you forklift instinct into being an ethical system, I don’t see how it works. I suppose one could argue that unconsidered consequences are also an ethical system but then so is rolling 2d20.

Oh… that’s some Plans level stuff right there

That’s not much of an argument. What, “argumentum ad obscure musical reference”

Maybe you’ve got issues, like those chrisitans who believe they were saved by jesus from their suicidal thoughts. Bit of a conversation stopper, usually.

Uh, questioning someone’s sanity is probably all kinds of foul. Yellow card, OK? I don’t know if you think you were being clever with your comment but it really was pretty substance-less. I expect better of you.

James Matta@#20:

As for trolleyology, I think I agree that in situation where you are dependent on reflex, there is no time for morality, you start to respond, without thinking, and then physics will take over. I sort of get what some people are saying that the point of the trolley problem is the justification of your choice, but I feel like if anything even a little similar happened IRL, where I had the time to think long and hard, I would probably spend that time thinking up a way to force a third option.

I agree. If we had time to think about it, we’d probably have time to realize that it’s a highly unusual situation. For one thing, there’s some guilty party who tied a bunch of people to trolley tracks – clearly we’re dealing with a psychotic philosopher. It would be risky to proceed without neutralizing them, first, perhaps by throwing them in front of the trolley, first.

I suppose someone could say that we’ve pre-considered certain attitudes, like a preference for helping people, and that we then act quickly in accordance with our ethics which are – shall we say – “broadly consequential” I’m not sure that works because what if one group of the track are CIA torturers and I don’t know that? I am unconvinced of our ability to understand the possible consequences of our actions to a significant degree in general. So “do whatever the F- appears to be the whole of the law” I will note that consequentialist reasoning is remarkably easy to graft onto an ethical problem after the fact.