The Probability Broach, chapter 15

This chapter opens with another of Smith’s fictional quotes put in the mouths of real historical figures. This one is attributed to Sequoyah (who in real life was the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary, but wasn’t an anarchist political theorist as Smith labels him).

“Are two people healthier than one person? Are two wiser? Then why believe they have more rights? History’s sadness is that sanity, wisdom, justice—the very qualities that make us human—are not additive, while one’s brute animal ability to do another injury, is. Two people are, tragically, stronger than one. Stripped to naked truth, that is the basis for all government, dictatorial or democratic. Can we not do better?”

—Sequoyah Guess

Anarchism Understood

Can two people be wiser than one? Yes! Was that even controversial?

It can go either way, to be fair. There’s such a thing as mob mentality, but there’s also such a thing as the wisdom of crowds. As a libertarian, you’d think Smith would be in favor of that: it’s always been proposed as an explanation for why free markets work, how it can be true that individual ignorance combines to produce a collectively rational result.

The wisdom of crowds is also why nations are governed by legislative bodies rather than kings, and criminal trials have a jury rather than leaving the verdict in the hands of a single random individual. There’s always a risk that one person will make a bad decision because of bias, ignorance or some other idiosyncratic reason. With a larger group, it’s more likely that individual prejudices and whims cancel each other out to produce a reliable result.

Back to the plot: Ed, Win and Lucy have assembled at Lucy’s house (“I’d counted eight cats so far, one sleeping in Lucy’s bony lap, another making his way up the difficult north face of Ed’s shoulder. I was trying to keep a kitten from perching on my head”) to discuss their meeting with John Jay Madison, a.k.a. Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. It turns out Lucy remembers him from the Prussian war—they fought on opposite sides:

“The Red Knight of Prussia himself,” Lucy declared. “‘Twas his Flying Circus put me afoot back in thirty-eight. Never forget it—there we were: The Pensacola an’ the Boise flankin’ my Fresno Lady, bearin’ northeast outa Cologne. They—”

“But that’d make him at least—”

“Ninety-six,” Ed said.

(Lucy, meanwhile, is 136. The North American Confederacy has life-extension technology, so no one finds this odd.)

Win wants to know why Madison was addressing Lucy as “Your Honor”. She admits that she helps mediate an argument now and then for “catfood money”:

“Pay attention,” Ed warned, “she’s being modest. Lucy’s a highly respected adjudicator and member of the Continental Congress.”

… “A distinction,” Lucy intoned, “utterly without distinction. Congress hasn’t met in thirty years, and I’m hopin’ like crazy it won’t ever have to again.”

Ed and Win are hatching a plan to break into Madison’s place and search for concrete proof of his world-domination scheme. Since Lucy holds an official position with the NAC, Win asks if she could get them a search warrant, so they can do this in an above-board way. But, of course, she can’t:

“Winnie, I got no official capacity. Nobody does, not even the president of the Confederacy. She only rides herd on the Continental Congress, if and when… What you and Ed are planning is unethical, immoral, and—”

“Fattening?”

“I was about to say, illegal—if we were the legislatin’ kind, which we ain’t. You two get shot up in there, nobody’s gonna say a thing. Madison’ll be within his rights. Or, he could sue you right down to your bellybutton lint.”

“Well, what are we supposed to do while he’s taking over the planet?”

“Son, we gave up preventive law enforcement long before we gave up law.”

What Lucy is saying is that in the NAC, even if you have knowledge that someone is plotting a crime, there’s nothing you can do but stand by and watch until they actually commit it. Attempted murder isn’t an offense; only murder is. (This world runs on Sideshow Bob logic.)

In our world, if you’re shot and narrowly survive, there’d be a police report. You could describe the vehicle that the shots were fired from, testify that one of the attackers named someone named Madison as the ringleader. Detectives would collect forensic evidence from the scene. All of this would provide probable cause for a judge to grant a search warrant, which could either turn up further evidence or clear the suspect’s name.

Also, if the police find evidence that someone is planning a serious crime—let’s say, holding secret meetings where they discuss a plot to kidnap and kill a sitting governor—they can be arrested for that. (That’s called criminal conspiracy.)

You don’t have to sit on your hands and wait for a would-be criminal to actually hurt someone before anyone takes any action. Smith denigrates this as “preventive law enforcement”, but isn’t that what we should want? Police who prevent crime from happening, rather than just punishing the perpetrators after the fact?

Meanwhile, in the NAC, the protagonists can’t legally do anything at all. A criminal can plot their crime in exacting detail without having to fear any consequences. Even to investigate a serious crime that’s already occurred, you have to break the law by trespassing in the suspect’s home. (When police are outlawed, only outlaws will be police!)

Their only chance, as Ed explains, is to break in to Madison’s house and find something that retroactively justifies their doing so. He can sue them for burglary, but they can countersue for a bigger crime. He’ll end up owing them way more money, and potentially getting exiled if he can’t pay. Win describes this as, “The end justifies the means”—all things considered, a frightening attitude for a cop to hold.

This goes to show that “total freedom” isn’t a political position that benefits everyone equally. It’s a much bigger advantage for those with evil intentions.

The way that L. Neil Smith writes his anarcho-capitalist world, it’s not just that they don’t have police or law enforcement; it’s that the legal system actively forbids these activities, even if carried out by private parties. The ordinary evidence-gathering and investigating that law enforcement would normally engage in are against the law here. Anyone who attempts them is risking death or a punishing lawsuit.

Meanwhile, activities that would be serious felonies in our world are perfectly legal and allowable. You can recruit conspirators, plot crimes, threaten people, stockpile weapons—and nobody can do anything to stop you.

This is a good argument for the importance of the Hobbesian social contract. We all agree to surrender some freedoms, in exchange for the protection of a state that’s supposed to keep us safe from those who’d do us harm. Ironically, the plot Smith wrote furnishes a good illustration of why this bargain of civilization is worth making.

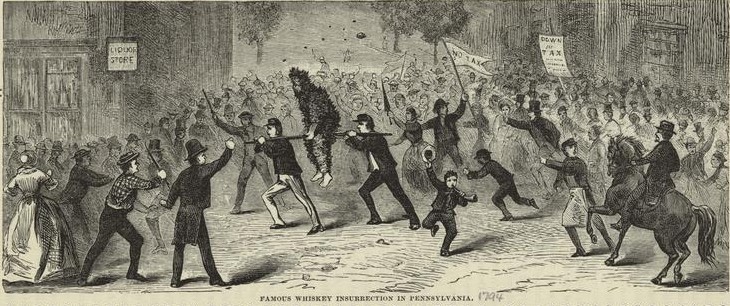

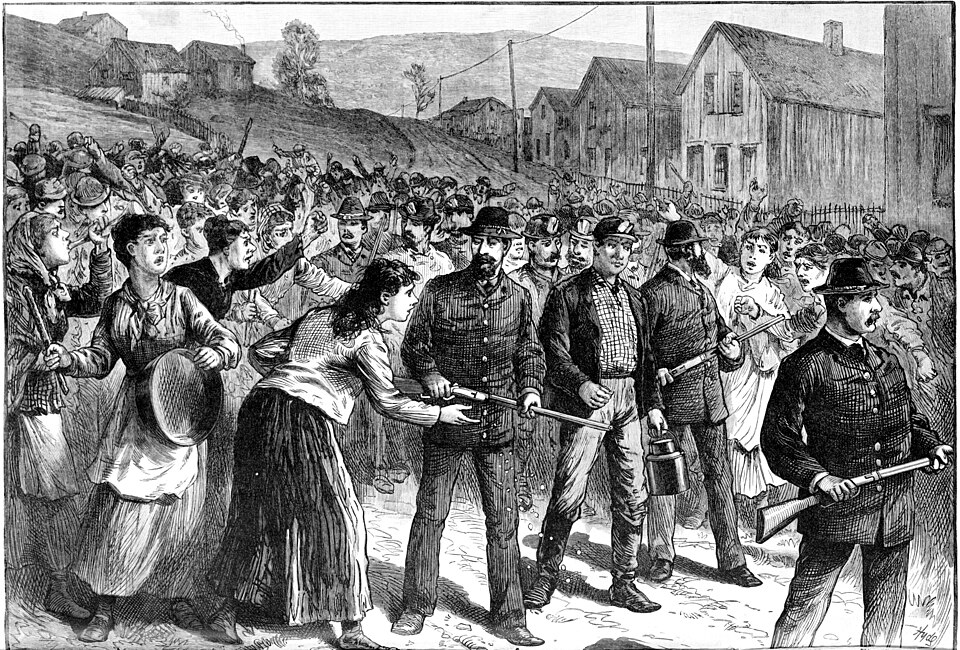

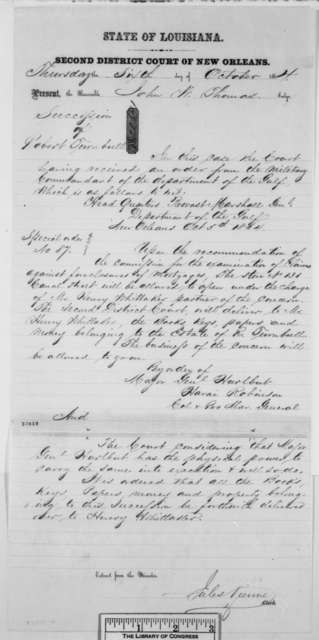

Image credit: Library of Congress

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: