I learned a surprising thing about Japanese swords the other day.

Some of the swords that are on display are replicas. [att-japan] I was swapping txt messages with a friend, regarding my favorite sword, Kanemitsu’s Sanchomo. (circa 1500) These are standard pictures of the thing:

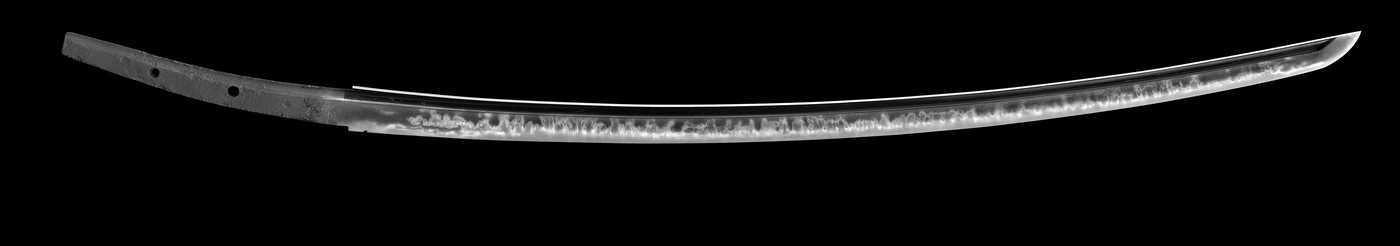

The nickname “Sanchomo” means something like “forest on fire” and it’s obviously a reference to that insane temper-line. Here’s a closer look:

Look at that chip in the edge, right before where the habaki (blade collar) would sit. Someone shed bitter tears when that happened! But, that’s the sort of thing that happens to swords when they are carried and used. Often, the history of a blade gets obscured – we have notes about its origin, and then its current condition, and other than that, a sequence of samurai lords hauled it around. Was it someone’s “daily driver”? We don’t know about the chip. Or, perhaps there are accounts in the many Japanese books of period sword-evaluation and registry, which haven’t been decoded. Markus Sesko has a write-up about what we know about the sword, mostly surrounding its nickname [sesko] “Famous National Treasure Sword” is a very real thing.

As someone who has tried to lay out a hamon (temper-line ) many times, that thing is absolutely gob-smacking. When the blade is quenched, you glob on clay leaving the edge clear, or with very thin coatings, and graduate the thickness along the flats and spine of the blade. The water used for the quench, the temperature of the blade, the thickness of the clay in spots, the metallurgy of the blade, the relative humidity of the time, the temperature of the quench bath, the composition of the clay and how dry it is, and god knows what all else are all factors. The smith who did that was able to visualize how it would turn out, and then hit it just right. Look at the temper-line near where the guard would be, and the kissaki (tip) – the temper line is less pronounced there, and is low to the edge to give it maximum strength, while the fancy stuff is in the central parts of the blade. Not only did the smith somehow plan out the hamon with that crazy pattern, he would have factored in how the expansion of the edge would curve the blade. Before being quenched it would have been close to straight; the curve results from inner tension between the larger martensite crystals in the edge and the smaller pearlite and cementite in the spine. An amateur like myself just clays up a blade and punts. If I were making blades every day for 30 or 40 years I’d probably understand the variables well enough to be able to control most of them, but blade-making was never my “day job.”

Now, it gets interesting.

Bizen Osafune (prefecture) is the home of a lot of traditional Japanese sword-making, and is where The Sanchomo was made. They are doing some fund-raisers to collect the 500 million yen (about $3.5 mil) it will take to buy the blade from its current owner, and put it in a museum. The “homecoming project” [att-japan] discusses the plans to add it to a sword history museum that would be on my “bucket list.” But there are pictures:

Wait, what?! The pictures are clearly labeled: “replica of Sanchomo”

Well, obviously it’s not the original. The original has a chip, and the tang shows oxidation like you’d expect in a 400+ year-old object made of steel.

See the problem? To make a replica of a legendary masterpiece, someone had to have the same mastery over their materials as the original bladesmith, then with cool passion and precision copied it. I can’t compare in detail the pattern of the hamon, but whoever was able to replicate the original just a little bit, probably replicated it all the way. Obviously there are going to be a few visible differences including the missing chip, but – “holy crap!” comes to mind. One does not simply 3D print a copy of a masterpiece, and the materials are pretty variable. Imagine that you were trying to replicate Michaelangelo’s David and got 90% of the way into it and the marble wasn’t right. Oops.

So, I started asking around and got back an answer that I thought was so quintessentially Japanese that I had to laugh. If you’re a bladesmith and you are starting to feel like you’ve really got a handle on what you’re doing (no pun intended) you probably wouldn’t call yourself a “master bladesmith” but, also, there’s no official organization that comes along and taps you on the head with an uchiko and says “you are now a master” in some solemn ritual. What you do is quintessentially Japanese craftsmanship: you make a replica of some other master’s work. Because if you can do that, you’re pretty masterly yourself. I mean, seriously, that “replica” of Sanchomo is a perfectly fine sword, a masterpiece in its own right, and whoever made it saw it go straight (probably with considerable ceremony) into a museum.

The Japanese Government has a status of “Living National Treasure” (the US should, but then we’d have jerkwads like Elon Musk trying to lobby to get on the list) which is conferred on a small number of people that are recognized as important achievers of Japanese culture. Basically, it’s like getting a form of super duper cool tenure for life. Gassan Sadaichi, the current master of the Gassan line of swordsmiths, is a Living National Treasure and one of the things that pretty much means is that his entire output of blades for the rest of his life is going to go straight to a museum, somewhere. And, for good reason. He has not produced a clunker for a very long time.

I thought that the whole “replicate a legendary masterpiece” maneuver was so quintessentially subtle and Japanese that I just had to laugh with joy. I’m grinning like a fool, just thinking of it.

That is, indeed, quite the test. Thank you for sharing this.

I don’t understand why the att-japan article is dated June 2023, talking about a fundraising effort from 2018. Even the schedule at the end shows a closing date of 12/31/19 at the latest.

.

There is a trading card online game called Touken Ranbu in which famous swords are depicted as bishounen (this is what Sanchoumou looks like in the game :D). According to the fan wiki, the crowdfunding was successful by 2020 and the sword now resides in the Bizen Osafune museum. Since the fandom has raised considerable funds for the preservation of other popular swords in the game, I believe they probably are right in this claim.

.

Here’s another shot of the blade, showing off the beautiful hamon on the left (I think the right side is the same as you included above).

Wow, that is some impressive polishing too. Amazing work all around

Borges’ Pierre Menard story comes to mind… though unlike the fictional Menard and his Quijote, here the swordsmith intentionally set out to create a faithful replica of a sword he knew well. What strikes me as similar is that, as you point out, the modern master had to stand very much in the proverbial shoes of the original 16th-century master, in this case because the sheer physicality of the medium (i.e. the steel) required it.

2,200-year-old bronze artifacts — including 7 swords — unearthed in China