(Also, my parents’ manyth anniversary! Congratulations!)

Today’s the anniversary of the day that the French stormed La Bastille, the prison that had become a symbol of the power of the monarchy.

The French Revolution, which turned into The Terror, is the best known of about 9 revolutions that took place in France – some more, some less successful. [stderr] [stderr] It was a tumultuous time, to put it mildly. And it was a long time – 1645 to 1848 or thereabouts.

The hussar’s style tunic with the sleeves cut off is a giveaway: 1832 (Les Miserables) [source]

“this is how we take vengeance on traitors”

Anyway, I thought I’d decorate this page with some picture illustrating the topic, but when I do a google search, it comes back with a lot of mish-mosh. There are people using pictures of the revolution of 1848 on articles about the revolution of 1789. Or the “Liberty leading the people” painting (because: breasts! shaved armpit!) which is from the revolution of 1832! Les Miserables is set in the 1832 revolution, which was a notable affair because of the way in which the French had professionalized mob rioting to the point where the standing army was not safe entering Paris. That’s when the “Aux Barricades!” cry dates from.

So, if you want to organize your French revolutions, think (roughly) this:

1645: The Fronde (Turenne and the Grand Conde)

1789: The French Revolution (July 14, storming of La Bastille, La Guillotine, Tricoteuses)

1799: Napoleon’s Coup (18 Brumaire, beginning of the 1st Empire)

1834: Aux Barricades! (Les Miserables)

There are layers of fractal detail around and between. Even the storming of La Bastille was not exactly a watershed; there were many events prior to then, which would have counted as the beginning of the revolution, such as the Women’s March on Versailles. [women march]

Uppity? You want Uppity? That’s a cannon!

La Bastille was stormed and the mayor’s head was paraded through the street stuck on a pike (did I mention, the French are hardcore?) and the explosion of violence began.

The collapse of France, from the greatest power in the world, under an absolutist monarch, Louis “L’etat c’est moi” XIV, tells us many things about the inertia of global power. When the USSR collapsed, many American ‘policy thinkers’ announced that Russia was no longer a power to be concerned with, and that history was at an end. One might have said as well about France in 1789. Stick a fork in it, it’s done. Hardly.

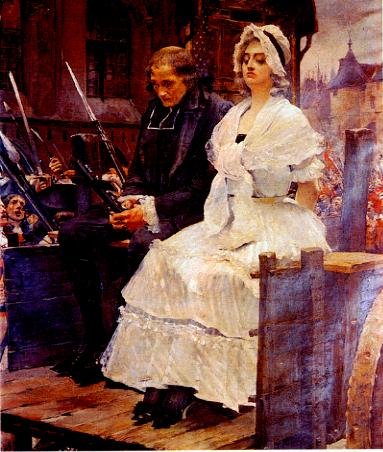

Marie Antoinette: dignity at the end

I despise the Santayana quote (“those the do not understand history are doomed to repeat it”) because it’s so facile; there are lessons, to be sure, but there’s also a fractal infinity of detail. The lessons, other than that history is not at an end, are that revolutions are never pretty and they aren’t a quickly resolved matter – it’s never the case that there’s a revolution and presto-chango, there’s a functioning republic a few years later. What there are are horrible times, more horrible times, more horrible times still, moments of hope, and more horrible times. When I encounter people who talk “we need another revolution” they have forgotten what happened to the loyalists in the colonies after 1776, they have forgotten the Whisky Rebellion and Shay’s rebellion and the civil war. Because, if you take a step back and look at the arc of US revolutionary history, and you’re Chou Enlai, you might see the revolutionary war and the civil war as being connected in the same way as the fronde and Napoleon’s rise to power. Or World War I and World War II. These massive disturbances have knock-on effects that are long-lasting and cause generations of pain.

Do not wish for revolution! Wish for the product of revolution: civil society in which the government is beholden to the people. The trick is to get the establishment, which always wants to accrue and cling to power, to understand that if they don’t negotiate in good faith with the people, they are also choosing revolution. The many French revolutions owe as much of their origin to the political mistakes of nobles, rulers, kings, and soldiers as they do to the passion and anger of the mobs.

Bastille Day usually meant one thing to me: fireworks! At the village near my parents’ house, Marcillac, the sapeurs-pompiers (firemen) would put on a fireworks display which usually ended with a weird ritual where a guy would climb under a wooden frame of a bull, covered in wet hide and fireworks all chained together, then run at the crowd with roman candles and whirligigs and bottle rockets shooting in all directions. I don’t recall anyone ever being hurt, though I’m sure there were some drunken skinned knees and holes burned in clothes.

(Sapeurs Pompiers is literally “sappers” and “pumpers” – the old military term ‘sapper’ is “the guy with a pickaxe who builds entrenchments or who digs mines under enemy fortifications. Basically, the grunt-worker who do what the “engineers” tell them. I love that the term is still in use.)

(Sapeurs Pompiers is literally “sappers” and “pumpers” – the old military term ‘sapper’ is “the guy with a pickaxe who builds entrenchments or who digs mines under enemy fortifications. Basically, the grunt-worker who do what the “engineers” tell them. I love that the term is still in use.)

I wish I had planned ahead and been able to go to some of the women’s rallies with a ton of Phrygian caps and tricolor rosettes and yarn and knitting needles to hand out.

At least Pompier is linguistically like pumper. What about Bomber? In Spain los bombers save you from bombers. Probably creating work for themselves. ;)

I don’t get Bastille day. It’s not a watershed moment, just a moment which is remembered. That makes no sense.

Shit, In Catalan (Valencian) its els bombers. In Spanish is los bomberos!.

The Roman “revolution” – i.e. the collapse of the Republican system and rise of the Principate – was a similarly drawn-out and extended process. Roman historians themselves often traced it back to the Gracchan unrest of the 130s and 120s BC, over a century before the final victory of Augustus at Actium. Between the agitations of the Gracchi for land reform and the Age of Augustus there was the Social War of the late 90s BC, the conflicts of Sulla and Marius, the Sertorian War in Spain, Sulla’s coup at the end of the 80s, the Catilinarian Conspiracy in 63BC and then the long series of wars between Caesar and Pompey, the Senatorial party and Antony, the Second Triumvirate and Caesar’s assassins, and finally between Octavian and Antony. And then it took Augustus 40 odd years to settle everything down to some degree.

It would not be going too far to suggest that a major factor in Augustus’s success was the utter weariness and misery of the Roman people after such an extended period of war and tribulation. I suspect a similar feeling may have been responsible for the support behind Napoleon in France.

Brian English@#1:

I don’t know if there was a watershed moment – the whole thing was kind of a slow-motion fall.

The Jeu de Paume probably was closer to the American declaration. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tennis_Court_Oath

But if you look at them, it’s similar: did the revolution start with the tea party? Or shots at Concord? Or the declaration?

I do think it’s off that they celebrate with a military parade. Because for the first part of the affair the military was the other side.

cartomancer@#3:

I hadn’t thought of that. I always sort of assumed the watershed moments were Marius and Sulla in the first civil war. And Caesar crossing the Rubicon, of course.

In a broad sense history repeats itself but in close it’s all fractal.

I do suspect historians of the future (if there are any) will see the US revolution and civil war as closely connected revolution/federalism/counterrevolution like in France, Russia, Rome

Seigneur:

My scattershot mind vaguely recalls you implying the revolution began when an English judge outlawed slavery and the proto-USian oligarchs smelt the wind and farted a great revolution….

Le maitre/Magister:

Your summary, that I’ve not quoted is a concise precis (is that possible?), but still magisterial. I want to say something clever and apposite, but no, you’re the expert and I think your summary captures revolutions, not a moment, but a drawn out saga where in the end the winning side stood up a bit longer than the losing one.

me too. Some sort of Whigish, great man of history formulation…

Ah yes, but we shouldn’t speak of such things. Really? Palm game? Tennis? Not at Wimbledon! In polite company we’d call that handball. In not so polite company, manual relief.

Brian English@#7:

Aaaaand you neatly busted me! If you noticed, I try to avoid the Great Man Theory. Except when I walk right into it.

To cartomancer @#3

This sounds interesting. Can you suggest me any books about this topic (the collapse of the Roman Republican system and rise of the Principate)?

A thoroughly delightful post. Happy Anniversary to the Ranums!

I hesitate to touch the topic in cartomancer’s corner of the woods but Tom Holland’s Rubicon was really good.

Self-similarity is what fractals do, n’est-ce pas?

Oh, and this is my nod to Bastille Day: Am I Paris?

Ieva Skrebele, #10

The standard work on the subject would probably still be H.H. Scullard’s From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133BC to AD68, though it is over thirty years old by now. More modern is Catherine Steel’s The End of the Roman Republic 146 to 44 BC: Conquest and Crisis (2013), and for the Augustan period J.S. Richardson’s Augustan Rome 44BC to AD14: The Restoration of the Republic and the Establishment of the Empire (2012). Or if you’d prefer something for a general rather than an academic audience you can’t go too far wrong with the relevant chapters in Mary Beard’s SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome (2015), for a general outline that fits into a much broader narrative of Roman history as a whole from the earliest times to the beginning of the 3rd century AD.

One of my daughter’s assignments in history last year was to write something about whether the French Revolution was ultimately worthwhile or a failure. She thought it was a failure, so I was contrarian and argued that it succeeded because it showed the oligarchs that there is only so far they can push. Every time a legislature votes to screw the poor yet again, every time a factory boss sits down across from a union rep, when they look over at the workers they’re going to see the shadow of Robespierre standing behind them. Sometimes that’s the only thing that could give them pause. That’s a success in my book.

I’ll echo Caine above with a Happy anniversary to the Ranums.

7/14 is a big day for us too, its my daughters bday, and she’s in France. (her bday is one of the few times i dont get an earful from her mother for calling her.)

A V Sandi Nack@#17:

Happy birthday to your daughter! It’s pretty impressive when a whole country has fireworks for your birthday.

…. I ought to know because my birthday is November 5 and I always wondered why the British acted unusually to celebrate it.

Well totally late but “Vive la France”.

An almost tolerable republic.

:) Remember, remember!

The fifth of November,

The Gunpowder treason and plot;