The paramilitaries in Portland enjoy freedom of maneuver as well as local fire superiority. In that circumstance, they have “won” because they are able to leverage their superior force wherever and however they want it.

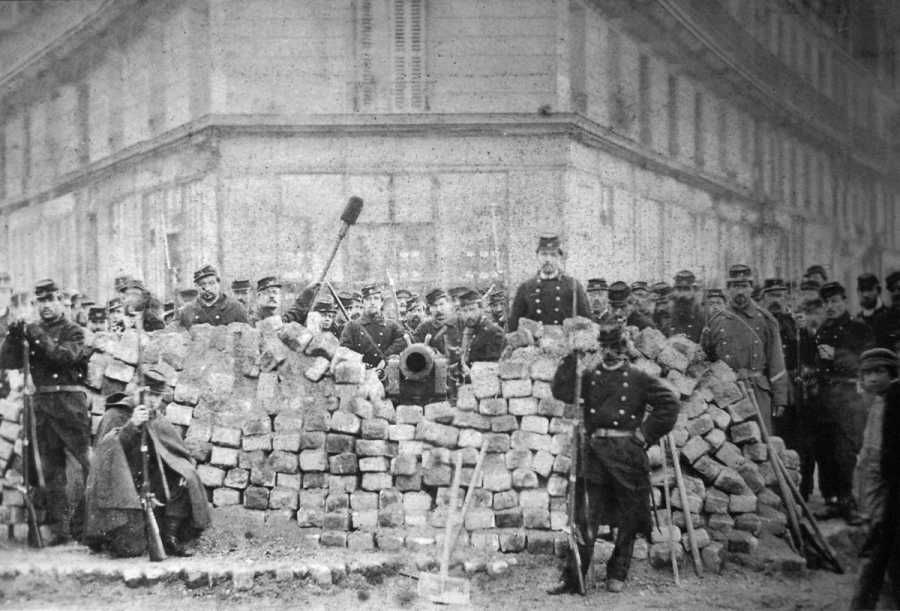

This is a barricade that was built on the Rue Voltaire (one block over from the hotel I prefer to stay in) during the events of 1871. France had serious political unrest, having just lost the Franco/Prussian War in a particularly humiliating defeat that also resulted in the capture and death of much of its political superstructure. Paris was garrisoned by militias, or national guard, whose loyalty to the state – which had just collapsed – was tenuous. There was a blip in which governance was gone and armed groups got to decide who owned the street. The French leaned back on the barricade-building skills that they had honed in 1830 and 1848.

The men behind this barricade are uniformed; they are regular military troops who displaced the insurgents. None of this was accomplished without loss of life; on various sides in the highly fluid situation were nearly 200,000 men under arms for some reason or another. It’s probably a testament to French level-headedness (<- that is sarcasm) that the casualties were not higher. At that time in French politics, casualties were not a big deal – they had just seen their standing military clubbed down like baby seals by the Germans, and were enduring a siege that included starvation and German artillery firing randomly into the city. I mention these things so that nobody mistakes what is happening in Portland for being similar to a real insurgency. If Portland dissolves into semi-formed military units roving the streets shooting at each other while being shot at by civilians, then that’ll be more like it.

The barricades in the 1871 revolution were impressive but we don’t have photos of the barricades from 1830.

To help you position these things in time: the barricades after the revolution (the first successful one) that overthrew the ancien regime in 1789-1799. Napoleon Bonaparte led a successful reactionary counter-revolution and made himself emperor, based on demonstrating remarkable ruthlessness when he used artillery against protesters on the 13th Vendemaire – the fabled “whiff of grapeshot”

Grapeshot was the original cluster-bomb: a leather cannister packed with thumb-sized metal balls, fired out of a cannon carrying a double powder-charge. In a stone city, with granite cobblestone streets, the shot would have howled through the crowd like demons from hell, obliterating whoever they hit into sprays of pink and white mist. Bonaparte demonstrated a ruthless political resolve that, fortunately, Donald Trump lacks and would run from with urine squirting down his golf slacks.

The next big revolution was 1830. Following Napoleon’s failure of politics by other means, France had a lot of angry veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, and opposing them was war-fatigue and the fear of a France supine at the feet of the victorious allies. The monarchy was briefly re-established, if only long enough for them to demonstrate that the Bourbons had not become more competent in the interregnum. The revolution of 1830 was fast, probably because of there being so many people with military training on all sides. You’re probably familiar with Delacroix’ great painting of Liberty leading The People. [wik] This has always been my favorite painting of the July revolution:

Scenes of July, 1830 by Coignet. The revolution was 3 days. It starts with the intact flag of the Bourbon monarchy, and ends in bloody shambles.

The revolutionaries organized effectively and developed the technique of building massive – and by “massive” I mean two story high, with parapets on top for sharpshooters – barricades, very quickly. Military units sent to knock down the barricades would march down the street in formation and, when they found themselves up against a veritable castle wall, being pelted by roof tiles dropped from 4 storeys up, they would turn to withdraw and find that another 2 story barricade had sprung up behind them. Then, the military unit would disintegrate into small mobs running through the buildings “sauve qui peut!” (save yourself if you can!)

Once rioters realize that they can mousetrap the forces of law and order, make them run, and take their weapons, then it’s all over. Mao and Stalin knew this. The military units garrisoned in public offices realized that they were cut off and surrounded, and began to disintegrate. It was over, soon.

The revolution of 1871, where we started, was the one that resulted in “La Commune” – the commune – a proto-communist semi-anarchic state that was like Seattle’s CHAZ except without croissants. (nobody had food because of the siege but they would have had croissants if there was any flour and butter) like CHAZ, the commune was crushed by the forces of reaction. But in the meantime it served as an interesting experiment – and warning – regarding popular governance. It turns out that people who find themselves unexpectedly in power don’t do a very good job of it because they have not spent their lives in the pursuit of power. Or; in the more unfortunate cases, there is a Bonaparte or Stalin in the crowd who does understand how to gain power, and then hell’s hounds are loose in the streets. That’s my round-about way of saying that I’m very happy that CHAZ was dismantled without the massive loss of life that would have resulted if an ethno-fascist with some charisma had managed to grab a microphone and create a disaster out of an incident. In the commune, they managed to create a disaster: the forces of the state had learned a lesson from the barricades of 1830 and they weren’t having any of that. They slaughtered the insurgents.

Bonaparte statue at place Vendome

The military, which was located at Versailles (the official seat of power in France until after 1871 when it shifted to Paris) slowly crushed the insurgents in often brutal house-to-house combat with 100,000 formed troops against – whatever. The military were a lot better at war a l’outrance, and better supplied and commanded, so it was a foregone conclusion. They began grinding the national guard (the rebels) to pieces slowly, and the national guard began disintegrating quickly. Then, came the shootings and executions and the unmarked mass graves.

Maximilien Luce – Paris street, 1871

The “boogaloo boys” are currently auditioning for the role of the national guard insurgents: idiots who thought to provoke a war against the government and who found themselves hopelessly outclassed and outnumbered, then in shallow graves.

Revolutions do not succeed unless the military join in (then it’s a coup) or declare they will sit on the sidelines.

The hotel de ville in ruins after 1871 (the headquarters of the commune)

I find that burned out buildings have a depressing similarity; I suppose its due to the physics of fire and stone – but that photo could have been Atlanta after Sherman was done with it, or Berlin, or Idlib. Builders rebuild, blood washes off, and business continues as usual.

The hotel de ville today

All of this is to say that Portland is nowhere near as bad as it could get, but I don’t think it will get worse because the parties involved haven’t built up enough of a head of despair and hatred to take the battle that far. Even today’s proto-fascist goons from DHS are probably not as dangerous as they wish they were – after all, they’re cowards that avoided actual military service in order to strut around beating on defenseless migrants. Militarily, they are cannon-fodder who cluster up in the street like they’re at a barbecue for tactical-wear models. Remember how the Dallas cops freaked out and pissed all over themselves when one not-very skilled sharpshooter started killing a few of them? The DHS goons would melt like butter if they were in a cross-fire from two sharpshooters. The good news is that the protesters have still not built up enough hate and anger that they’d cheer.

I guess I find this all comforting, because it reminds me that the situation has much, much, worse to get before the shit really hits the fan. Some of the people involved would probably not mind having the feces fly, but those people are the kind of cowards who hide in a bunker to give their orders. Bonaparte was sitting on his horse, staring right in the eyes of the mob, when he ordered the grapeshot to work. He would not have flinched from the sight, he had seen worse, would cause worse again and again. I find all of this comforting because it makes me believe that there is no Bonaparte or Stalin on the scene, and there’s no sign of one. The popular ground-swell of anger is justified anger, not deep hatred – it’s not too late for the state to fob them off with empty promises of reform from Nancy Pelosi and Joe Biden. The bitterness that engenders may be enough.

Next time, it’ll be the fire.

I have written elsewhere about Peter Watkins’ film Threads [Edit: this is incorrect] and why everyone should see it. But Watkins has done other brilliant and fascinating stuff, including Culloden – a sort of faux-reality journalism take on the famous battle – and he did a faux-reality documentary on the commune. It’s long and weird and dark and brilliant. If you’ve got the time, it’s really quite a thing. I’ll do a review of it someday if we all survive.

It is important to understand the French revolutions and, particularly, the commune in context. The Communist Manifesto was written in 1848 and the commune leaned heavily on marxist tropes. Reactionary governments and their industrial magnate and banker masters were profoundly terrified of marxism as a threat because they mistook the marxist ideology as the motivation behind the commune and the Russian revolution of 1923. These events may be seen as a political cri de cœur of the unhappiness of the working class. I believe all the communist ideology was an unfortunate smoke-screen for just “we are mad as hell and we’re not going to take it any more!” but a population that is being screwed by inequality masterminded by oligarchs needs a framework into which to contextualize their pain. The marxist framework made sense in a time when industrialization and industrial capitalism were driving massive inequality and brutal repression. Today, in the US, it’s baked-in USain racism and brutal policing. Between the Russian revolution and the commune, the UK/US governments became absolutely terrified of worker revolts, as they should have been. They managed to keep the people in line – in the US using a racist “divide and rule” strategy, coupled with brutal crackdowns on anarchists and communists by the secret police.

If the US establishment has any sense, they will defuse BLM by foisting Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi over top of us, to wring their hands and explain that “it’s hard” – i.e.: Obama 2.0 – and giving just enough to get people to sit back down again. It’ll push the clock back another 8 years. I’m happy to see that most of the protesters are not reaching for anarchist or marxist tropes for their framing. As much as I appreciate anarchism as an ideology, I wish that the anarchists currently in the situation would shut the fuck up about anarchy and start talking about corporate greed and racism; but it’s too late. Besides, the forces of reaction were going to find someone to demonize, even if they just made up their Immanuel Goldstein; truth is no obstacle to the power-hungry.

Do you have a second favorite hotel to stay in during the events of 1871?

I think that one disadvantage that the commune had in fighting the French army in 1871 was that in the preceding decades, Napoleon III had rebuilt large parts of Paris with wider streets. This may have been aesthetically pleasing, but the real point was to make it easier for troops with artillery to maneuver through the streets, and more difficult for insurgents to quickly build barricades and trap those troops. It turned out that this didn’t help Napoleon III at all, but it made it easier for the Third Republic that succeeded him to defeat the communard uprising.

CHAZ turned into CHOP, CHOP turned into Altamont 2020.

These are the good old days.

starskeptic@#1:

My other favorite hotel is on Place Nation. In the first revolution, that’s where the guillotine was set up. It was a quiet part of town in 1871.

“Hotel with view of guillotine: 5 star view.”

Watkins did not make Threads.

I, too, at one point a few decades back spent a lot of time reading up on the revolutions of 1830 and 1848. I even wrote a pair of live-action role-playing games based around them.

Part of what I got about the course of those revolutions is that they start off when the middle classes start accumulating a lot of financial clout without any of the political power that they feel should go along with it. So they (particularly the younger ones) start agitating for “rights” (by which they mean privileges) that they feel they deserve.

Then the lower classes start to rumble and stretch and say “Yeah, how about those rights, hunh? And say, why do we even need private property, anyway?” And the middle classes say “Revolution? What revolution?” and go running back to the aristocracy.

I am just as glad that CHAZ didn’t persist, though. If (hopefully when) trump loses, I worry that the boogie boys are going to start mushrooming up a bunch of little Bundie compounds around the country, and we don’t want to be accused of hypocrisy when we say that no, you can’t just declare autonomous zones where federal laws don’t apply.

You do mean the cops, right? I’m honestly not clear… (and not paying close enough attention to the developing situation in Portland).

@sonofrojblake:

Except that a lot of the problems aren’t due to the local cops so much as Border Patrol agents, trained to deal with people who aren’t necessarily American citizens which makes it easier to ‘Other’ people. ‘Paramilitary’ is about the right word.

Though, of course, they also give the local cops excuses to fall back on bad habits.

@Rob Grigjanis:

You are correct. I had it confused with The War Game.

I discovered and watched Watkins at around the same time as Threads and everything got all mushed together in my memory.

sonofrojblake@#7:

You do mean the cops, right?

I mean the federal marshals/DHS. They look like a bunch of amateurs cosplaying soldiers. But I refer to them as “paramilitaries” because they are not in military uniform but are trying to look it. They are also not carrying US gov’t issued weapons.

Very informative. It makes me realize how lucky the U.S. has been up to now. Whenever we’ve faced an existential crisis, we’ve had a great man to lead us. In the Revolution, we had Washington; the Civil War, Lincoln. In World War II we had FDR. Seems like our luck has run out.

“I find all of this comforting because it makes me believe that there is no Bonaparte or Stalin on the scene, and there’s no sign of one.”

Until Lenin died, Stalin was content to be one of his lieutentants while setting himself up as the successor. Now there’s no comparing Trump and Lenin, but some of the characters Trump has dredged up and elevated are in it for the power, much like Stalin. Competence may vary, but it’s easy to imagine that at least some of them – e.g. Bannon – might fancy following in the footsteps of Stalin or Bonaparte.

Mind you, the career paths are very different these days, which will shape these people to some degree. Stalin did work his way up the revolutionary hierarchy and got his hands dirty with not-so-petty banditry and raids. These days characters like Miller or Kushner engage in different kinds of banditry and their personal risks are limited to drawn-out litigation and bad press.

—

Re: Publicola (#11):

Would you mind terribly if we swapped “great man” out for “competent leader”? I think it’s the latter people really want in a crisis and the former label usually doesn’t survive closer scrutiny.

And I will concede that even “competent” is more of an after-the-fact assessment that depends on context. Washington? Won the revolution. Lincoln, handled the secession thing sort of okay if you like the idea of a big, hulking US.* FDR? WW2. Stalin? Uh, WW2 and … other … stuff? Good at what he did (make Stalin more powerful) but definitely not a great man.

*Deeply flawed, courtesy of, among many, Washington.

@Jenora Feuer/mjr –

“a lot of the problems aren’t due to the local cops so much as Border Patrol agents”

“I mean the federal marshals/DHS”

I hadn’t appreciated the distinction, but I do now, thanks.

I appreciate the perspective it’s somewhat reassuring, but now that Trump has decided it’s fine to use a secret police on US citizens for reasons other than that they look hispanic, it wouldn’t surprise me to find them active in any swing state city close enough to 100 miles from the border on November 3rd.

The US military does, really, understand how to counter an insurgency without resorting to classic Roman methodologies of massacre and punitive expeditions. The later is messy buy effective, at least for a time. The newer understanding centers around one undeniable fact; happy people don’t create insurgencies. It took a couple of hundred years for a significant number of military thinkers to accept the immediately obvious but we can’t say they can’t learn. Unfortunately the political side often prefers to go for the short term gains of strong-arm tactics.

Along those lines: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTNqT6LcW1o

IMHO he gets the basic idea right. My list: Listen to what the people feel. Differentiate between need and want. Focus on making life better for the majority of the people. Select a few issues and show progress. Maintain presence and progress long term. Build relationships and respect by being a reliable partner. Give locals control. Get buy-in and build institutions.

The way to prevent bloody insurgency and revolution is to make make sure that peaceful change moving toward justice is easier than the alternative.

@Publicola #11 & @komarov #12:

I think komarov brought up most of what I’d say about the idea of “the great man” but there’s on more very poignant and practical bit that wasn’t mentioned: Great Men are in the past. They’re dead. They aren’t fixing any of our problems because they don’t have problems now.

We’ll need to fix things ourselves this time around just like they did.

As a minor addition it’s also rather annoying how Great Men who think they’re Great Men in their own time tend to take this as license to be greatly disappointing and get away with it. It tends to make one think that with outsized virtues one gets to have equivalently outsized flaws.

And for what it’s worth it’s never one Great Man. It’s one person standing at the head of a movement.

I’m sure everyone knows all these things, they’re just worth remembering anytime this concept comes up.