Warning: I get a bit ranty.

A surrealist is walking down the street, and sees a banana peel in his path; he says, “Mon Dieu! I am going to fall down again!” and keeps walking.

The Senate Intelligence Committee is having meetings about “Worldwide Threats” – an elaborate simulation of thought, in which they pretend that the United States is not the biggest worldwide threat, even to itself. But we cannot take our share of blame because then some rocket surgeon genius would say “well, then stop.” That way we can talk oh, so seriously, about what to do about those threats, especially if that means employing America’s multi-purpose crisis response: dropping bombs on people.

The chair of the meetings is apparently Senator Obvious, because the carefully-chosen topics are mighty Obvious, indeed. I’m going to focus on two of them, because they touch on my professional expertise, namely Information Security.

1: Lies

The first topic is pretty easy: [business insider]

The first topic is pretty easy: [business insider]

Sen. Mark Warner, the ranking member, told the panel that the US was “caught off guard” by the way Russia weaponized social media during the 2016 election to push pro-Trump propaganda and sow discord within the country.

In addition to using Twitter and Facebook to spread fake news, Russia-linked Facebook accounts also bought ads focused on exploiting American divisions over issues like race and immigration.

The accounts’ activity did not stop at posting controversial memes and hashtags — many even organized events, rallies and protests, some of which galvanized dozens of people.

The US Senate, then, is now up to date with the idea that “propaganda works” – all of them having gotten their jobs through relentless propaganda; the revelation that social media can be used to affect US politics (and other nations’ politics, too!) dates back to around 2004 when Facebook was founded and took over for MySpace, and 2006 when Twitter was founded. Immediately, those platforms became channels for “astroturfing” (what politicians call their propaganda) and outright propaganda (the other guys’ propaganda).

What, O what can we do about this? Are we doomed to walk forward and slip and fall on the banana peel?

There is an answer, and it’s scarily obvious. The two party system has almost stumbled on it several times, but they recoil in horror: return to valuing authenticity. That’s a polite way of saying ‘stop lying so much.’ Basically, they have two options:

- Lie more

- Lie less

My prediction is that, since they depend overmuch on lying already, they will find themselves unable to return to authenticity as a value, so social media will continue as it began: a trading-ground for marketing (lies), political positioning (lies), and disinformation (lies). After all, it’s exactly what happened to television. How can anyone complain about social media being full of fake news, when Fox News and The New York Times are putting on such a great demonstration of old-school social media manipulation via lies?

2: Interfering With Elections And Sacred Democracy

Coats warned that Kremlin influence operations would continue for the foreseeable future, and that Russia’s next target is the 2018 midterm elections.

“We need to inform the American public that this is real … We are not going to allow some Russian to tell us how we’re going to vote,” Coats said. “There needs to be a national cry for that.”

Collins told Coats it was “frustrating” that Congress has not yet passed legislation to help states combat Russian cyber attacks on critical election infrastructure. She then asked the DNI about NATO’s assessment of Russia’s influence operations.

“Mon Dieu! I am going to fall down again!”

It’s also a bit of a lie, to protect someone’s incompetence. Let me explain: back in around 1995 when the internet was starting to be a Big Thing and the Soviet Union had collapsed, there was this idea that there was going to be a “Peace Dividend.” People in the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community were, frankly, scared that there were going to be budget cuts. Then, Winn Schwartau wrote a book called Information Warfare [amazn] that was, frankly, a lot of bullshit about then-nonexistent cyberwar capabilities that have since come into existence. Suddenly, the intelligence community and DoD were excited: here was a new “battlefield domain” to spend lots of money on! And spend money, they did. The NSA established an “information assurance” program (and an offensive program for dirty tricks) the CIA established an “open source intelligence collection” program (and an offensive program for dirty tricks) the Army’s Defense Information Systems Agency established a cyberwar defense operation, the National Institute for Standards and Technology started writing security policies, the NSA started writing security policies, various federal agencies started writing security policies, and the FBI got AOL accounts and thought they were on the internet. There was a tremendous amount of money spent on computer security from 1995 on; even if you accept my guesstimate that 90% of it was spend on offense, the 10% spent on defense would have amounted to billions of dollars. There was a time, and I was in the thick of it, when NIST and NSA were actively competing to see who could set standards for federal agency security. Meanwhile, the federal agencies more or less did their own thing – some competently, some not so competently. US Government attempts at actually doing computer security floundered and sank without a trace – mostly because of policy enforcement problems: it turned out to be difficult for the NSA to tell the State Department how to run their computers, because that meant (effectively) letting the NSA control part of their budget, which is bureaucratic death for an agency.

I was a participant in some of those meetings (in my capacity as a consultant to a consulting firm that was consulting to NSA) and I remember Very senior people from NSA telling equally senior people from CIA “if you want to send us your telemetry, we can help you guys defend” and the CIA responding, “if you want to send us your telemetry, we can help you defend.” Then, they both did a little tap-dance to the tune of an old Broadway chorus line, and belted out in harmony, “no way in hell will we ever let you see our data, but we’d love to see yours!” Meanwhile, those jokers were building parallel offensive stacks and not sharing them at all – this was going on in every agency that was part of the vast intelligence apparatus. (I’m not going to get into what SPAWAR, AFWIC, NPIC and NRO and DEA and everyone else was doing except it all involved spending money like Wall Street investment bankers tunneling into a mountain of Mexican flake cocaine, nose-first)

I was a participant in some of those meetings (in my capacity as a consultant to a consulting firm that was consulting to NSA) and I remember Very senior people from NSA telling equally senior people from CIA “if you want to send us your telemetry, we can help you guys defend” and the CIA responding, “if you want to send us your telemetry, we can help you defend.” Then, they both did a little tap-dance to the tune of an old Broadway chorus line, and belted out in harmony, “no way in hell will we ever let you see our data, but we’d love to see yours!” Meanwhile, those jokers were building parallel offensive stacks and not sharing them at all – this was going on in every agency that was part of the vast intelligence apparatus. (I’m not going to get into what SPAWAR, AFWIC, NPIC and NRO and DEA and everyone else was doing except it all involved spending money like Wall Street investment bankers tunneling into a mountain of Mexican flake cocaine, nose-first)

Somewhere around then, the FBI got an internet connection.

From 1995 to 2016, there was a gigantic game of “hot potato” while various federal agencies announced that “We are responsible for cybersecurity!” so they could try to grab a big chunk of budget, spend it on offensive tools, and fail to improve federal agency security at all.

Then 9/11 happened, and the Department of Homeland Security was created. “We are responsible for cybersecurity!” they cried. “They are responsible for cybersecurity!” Congress yelled. DHS’ budget was huge and they had top-level in the org chart over several of the sub-agencies, and what did they do? Mostly, they hired contractors. They hired gigantic numbers of contractors, and outsourced a lot of stuff. Some of it worked pretty well – the US Marine Corps’ network, for example, was outsourced to General Dynamics, who also run security for them, and it’s not as horrible as it could be. Some of it didn’t, like the FBI’s multiple “virtual case file” projects that cost over 1 billion dollars in three attempts to produce something like a Wiki. DHS began issuing alerts and starting educational programs (those weren’t bad) – the alerts were written for them by computer security trend-tracking firms, and were pushed out with DHS’ logo dropped on top; I know because I wrote some of them but didn’t have the clearances to look at them after they had the DHS logo added.

Following that, the next big event was the great US/China cyberwar of 2010-2012, which … didn’t happen. Basically, the US complained a tremendous about about Chinese hackers being all over US networks. And, they probably were! Why wouldn’t they be? Around 2010, anyone with basic hacking skills who wanted to be in any US agency network could be, especially if they had the support of a nation-state. Given the rate at which information security was being outsourced, any intelligence officer worth their weight in warm spit would have been placing pigeons at beltway bandits. The reason the US Government is so pissed off at Edward Snowden is only partly because of what he stole: Snowden and Manning demonstrated conclusively that the US Government (including the overrated NSA and CIA) had learned nothing since the Walker spy ring had gutted NSA security, Aldrich Ames had sold the CIA’s biggest secrets for the price of a motorboat and a house in Potomac, and Robert Hanssen had humiliated the FBI. These profoundly important “wake up calls” resulted in a flurry of activity, most of which was finger-pointing, and screeching to Congress for “More Money!”

Following that, the next big event was the great US/China cyberwar of 2010-2012, which … didn’t happen. Basically, the US complained a tremendous about about Chinese hackers being all over US networks. And, they probably were! Why wouldn’t they be? Around 2010, anyone with basic hacking skills who wanted to be in any US agency network could be, especially if they had the support of a nation-state. Given the rate at which information security was being outsourced, any intelligence officer worth their weight in warm spit would have been placing pigeons at beltway bandits. The reason the US Government is so pissed off at Edward Snowden is only partly because of what he stole: Snowden and Manning demonstrated conclusively that the US Government (including the overrated NSA and CIA) had learned nothing since the Walker spy ring had gutted NSA security, Aldrich Ames had sold the CIA’s biggest secrets for the price of a motorboat and a house in Potomac, and Robert Hanssen had humiliated the FBI. These profoundly important “wake up calls” resulted in a flurry of activity, most of which was finger-pointing, and screeching to Congress for “More Money!”

What never did happen was a consistent push toward securing government systems. The great cyberwar of 2010 resulted in a bunch of talking-points about the Great Chinese Peril (“ohmygod the Chinese are going to be in all our routers!”) (Ha, joke’s on you, that was NSA that was in your router!) but what should have happened is for someone to realize that, yes, system integrity is paramount, and secure supply-chain management is a thing, and started designing a security-centric technology sourcing program. Around about the time I am describing, Cisco Systems did start building a secure supply-chain program and thinking about where their code and components come from. Several other businesses did that, as well. But their huge customer, the US Government, did nothing except complain about how thoroughly the Chinese owned all their systems. OK, that’s not fair: the NSA responded by developing a ton of attack tools, which they subsequently lost control of. So did the CIA. So it’s not as if the US Government did nothing; they did nothing effective on the defensive side of the equation. The great cyberwar of 2010 was when the US Government first spotted the banana peel, off in the distance, and thought, “oh, look, a banana peel.”

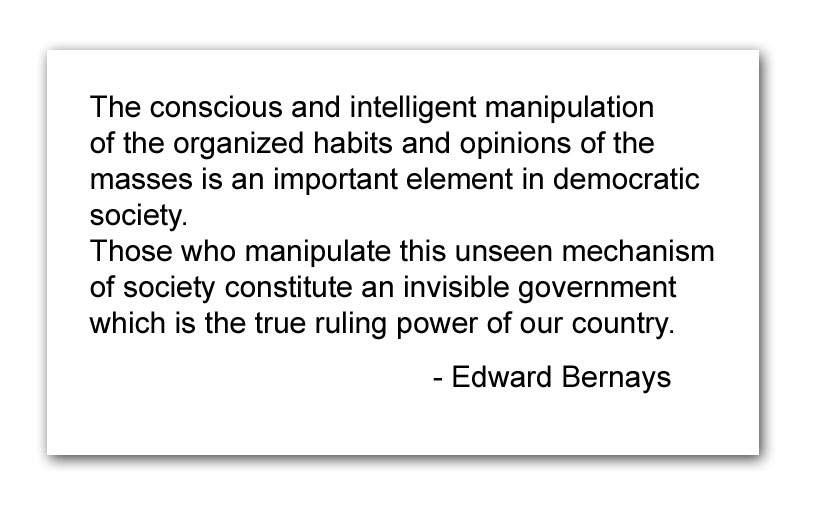

Now we get to 2016. Something that the US was completely unprepared for, except for that it was predicted in Winn Schwartau’s lousy book (if not in Edward Bernays’ Propaganda) – it was the entire reason why the whole edifice of computer security for the US Government, post 1995, had been erected.

Meanwhile, in the commercial sector: businesses had to deal with hackers, industrial espionage, insiders stealing data, vulnerable systems, and so forth. I sat in on many of those meetings, too. Sometimes someone from the FBI would come and say something helpful like “we’re here to help” and then, when asked for traces or information about what they were saying hackers were doing, “sorry we can’t give you that.” Having sat in all sides of those meetings, I got a bit skeptical when the FBI (and later the NSA) started saying “give us your data and we’ll look at it and tell you what’s going on.” I had been in that meeting before, so I asked them if they would share information about blackhole nodes and ports to monitor.

I’m digressing; you need to picture me ranting this at the screen, with flecks of foam flying across the intervening space and sticking to the panel. This is serious business. I devoted my life to making this problem better. And what I hear is the intelligence community saying, basically:

“Mon Dieu! I am going to fall down again!”

This is a banana peel that has been ineluctably sneaking up on them since 1995.

This is the consequence of failure.

This is because the agencies “responsible for cybersecurity” spent 90% of their effort on offense and never tackled the very difficult problem of implementing a national cybersecurity strategy. Obama’s national cybersecurity strategy tsar, Howard Schmidt was an old acquaintance of mine and when I asked him how things were going he’d just shake his head and say, “it’s political.” In a brilliant attempt at revenge he threw my name into the hat when they were looking for his successor, but I was saved by the anarchist logo on the front page of my personal website.

So, gaze upon the spectacle of the US intelligence community, which spends between $25bn (declassified cumulative budget in 1995) and $60bn (2016) per year for 21 years – and says:

The intelligence chiefs unanimously agreed, when asked, that they had seen no decrease in Russia’s influence operations and that the Kremlin would continue targeting US elections, beginning with the 2018 midterms.

I mentioned the commercial world, earlier, because one of the other things I have done a lot of since 1995 is incident response. I’ve never done incident response for a Federal Agency because I am afraid I would just start screaming and hitting people and they’d have had to tase me. I have, however, been involved in technical analysis and designing reaction plans for two incidents that I am pretty sure that you’ve heard of and a third you probably haven’t. What is fascinating about how companies respond to a security breach (the good ones, anyhow) is: They change things. Sure, there are some, like Equifax, that just realize they don’t owe their customers even an apology, and keep plodding along – but others have dropped millions of dollars, quickly and effectively, into dramatic large-scale changes in enterprise infrastructure and practices. I have seen FORTUNE 500 companies go from sprawling badly-designed WANs to tightly laid-out virtualized infrastructure with layer 7 firewall segregation between zones, common authentication and logging architecture, performance metrics, and 24/7 security operations centers staffed with top-notch analysts. I have seen large companies suddenly decide to take security seriously and tell their users how to behave and make it stick (failure to do that is the root of 99% of US Government IT security disasters) – and I have seen large companies sensibly spend their security investment on solid defense because, well, offense is not an option for them, and they were smart enough to realize that you cannot defend yourself by attacking the whole world. I have seen Chief Security Officers (CSOs) of large companies tell the CEO “really, we need to change how we do this and here is why” and see change happen. Yes, I’ve seen incipient disasters like Equifax coming a long way off, but most businesses recognize them as examples of “how not to do it.”

So, look at the Federal Government’s response to the 2016 election hacking:

“Mon Dieu, I am going to fall down again.”

There are practical things that should be done, and could be done very quickly in any well-run business. First off, the election machines:

– It is an utterly stupid idea for each state to have its own election machines, which report in a state-dependent way, have no audit trail, no high integrity design, and are purchased at tremendously inflated prices from the lowest bidder.

The US Government needs to accept that election machines are critical national infrastructure and have NSA design and build a networked vote collection system that cross-records votes using hashes so voters can verify their votes were tallied and that there are no ‘additional’ votes; these systems should run atop a trusted operating system designed to TCSEC A1 target, with mandatory access control and a Ring0 kernel running on trusted hardware. Those systems should use a completely private network with point to point encryption over an open core that is closely monitored. Does that sound hard? It’s basically how the NSA’s Secure Telephone Unit (STU-III) worked except hopefully not so slowly. That system needs to be evaluated not just by the builders, but by outside experts as well. Last, but not least, it needs a design target life-span of 20 years; a new system refresh to be begun in 15 but the overall system design is to not require patching or upgrades for at least 2 decades. This is not rocket science. Well, actually, it is – it’s how NASA used to build systems. And it works.

The voting machines at DEFCON’s voting machine hack village usually survive a few hours. Hours.

The US Government needs to accept that having a massive swamp network that is classified “system high” but which has over a million users is not just “a disaster waiting to happen” it’s a “disaster in progress.” The entire system by which access is granted needs to drop back to a “need to know” not “need to share” model, and – at a minimum – there need to be strong audit controls so that in the event of a leak, it can be narrowed down to within a reasonable time-period. Yes, it means that more work needs to be done, to manage secret data effectively. Here is one suggestion: reduce the amount of secret data to 1/1000th of what there currently is.

Lastly, government networks need to be designed in the manner of state of the art business networks: data centers firewalled off from zoned networks with access controls and audit between the zones. Desktops (which get malware because people click on naughty things) should not be populating the same networks as servers, database servers, mail servers, and infrastructure platforms. Administrative access must be restricted and systems must be under configuration management; the cost of individually managing desktops is absurdly high and it’s wasted money.

Those are basic recommendations that I know every CSO in corporate America is pushing toward (except for the few, like Equifax… hey, I hear they’re looking for a gig) Those are the basics. There are more advanced things that government IT absolutely should be looking at, such as repeatable/manageable/recoverable private enclaves that can be instantiated, used, and destroyed on demand. That’s basically what you can do with Amazon AWS or other cloud servers: have a system image that represents a correctly-configured well-managed email server, or a correctly-configured well-managed web server. You build those and then people stop using the old, broken stuff. If they complain, tell them they need to look for a job elsewhere; I hear the Russians are hiring. I have described this before; it is utterly absurd that the US Government is sitting there watching the banana peel creeping closer and closer and nobody has thought to offer a cloud-based secure communications+VPN+recovery enclave for political campaigns while they are in progress. I know the CSO at a major Hollywood movie studio whose organization can and does offer exactly that sort of “temporary secure enclave” set-up for short-term or long-term use by directors that need to set up sharing and communications with outsourcers or vendors, but who want to tightly control where their data is. Some entrepreneur ought to be offering “political campaign office communications system in a box” cloud services except – as far as I can tell – the people who run political campaigns are the most IT-incompetent self-important imbecile users that there have ever been. They would just continue using Exchange servers on Windows 2000 with SMB file-sharing on Windows XP boxes connected to the internet behind a bargain-basement ‘stateful firewall’ with NSA and Chinese holes in it.

None of this is easy, but it’s a lot easier than watching that banana peel creeping down the sidewalk toward you, and having to tell Congress, “we have no fucking idea what we’re going to do in 2018 except we know the Russians are going to fuck us up.” I would commit hara-kiri in the hearing-room rather than have to admit that I was involved in such a massive, systemic failure to respond effectively to something so bloody obvious.

When these useless, corrupt, hacks start asking Congress for more money – hand them a sharp knife and say, “expiate your shame.”

Beating Around the Bush Administration

All of the technical kerfuffle, fuss, and bother I described above is irrelevant, should the US, Russia, and others pursue the only course that makes any sense at all – the one approach that is guaranteed to be effective, inexpensive, and ethical: de-escalate and negotiate. The US, UK, Russia, and China have proven in the past that they are capable of sitting down, establishing a legal and obligational framework, and (mostly) behaving themselves. They did it with biological weapons (almost completely) and nuclear weapons (kind of) – they could do it with cyberweapons.

You may find this hard to believe but it’s true: during the apex of the great China/US cyberwar of 2010 (which didn’t happen) China was proposing diplomatically to the US that there be joint talks with Russia, the UK, and others, to establish international standards defining the dividing-line between “international cybercrime” and “state-sponsored cyberwar” – basically scoping out the battlefield and deciding what’s off limits and what’s acceptable. The US, naturally, said it wasn’t interested.

The US, naturally, wasn’t interested because the US intelligence community believes (probably correctly) that it is ahead of everyone else in the game – in spite of its constant poor-mouthing and complaining. It’s the “cyberwar gap” scenario from 1957 and 1962, all over again. An international framework that said things like “let us all agree not to put trojan horses in anyone’s critical infrastructure” amounts to taking away their shiny new toys. It’s that simple.

International agreed-upon frameworks work, and work all over the place. Is there cheating? Of course there is cheating, but the framework does the all-important thing of defining what “cheating” is and providing a set of options (economic or retaliatory) that allow a cost-benefit analysis for the potential cheater.

The US is perfectly capable of turning to Russia and saying, “listen up, we won’t crater your economy by bottoming the price of oil with the help of our Saudi friends – like we did in 2015 – if you promise to stop messing with our pseduo-democracy like you did in 2016.” And, “let’s establish an international standard for attributing cyberattacks to nation-states, and place determination of fact in the International Criminal Court so that if someone misbehaves we don’t get into an escalating cycle of retaliation.”

Shocking, but it could just work. And implementing it involves no massive infrastructure or technology shifts – though, once there was a cybercease-fire in place, everyone would do well to take a deep breath and look to their defenses, anyway. Everyone still needs to keep the run-of-the-mill hackers and cybercriminals out of their systems and it’s never a bad idea to level up one’s IT expertise.

Buried in all of this is the main point: the US is not interested in negotiating about cyberwar, or doing anything more than complaining about the Russians “Mon Dieu! I am going to fall down again!” because any kind of systematic approach to de-weaponizing and de-escalating is seen as removing one of the US’ most entertaining weapons of privilege: its colonial control over the internet, and core internet technologies.

With that nasty, bitter truth on the table, I have said enough. We can resume watching the cyberkabuki performance coming from the US intelligence community and the corrupt US Congress. They dance beautifully, don’t they? They were supposed to defend this mess, and look at them now, begging for money, ye mortals, despair.

The joke was originally a “blonde” joke; it was one of my favorites back when we still used to tell them. I reformatted it and turned it into a joke about surrealism, rather than a joke about people being stupid. This is not to imply that surrealists are stupid; I could have just as easily used a taoist sage. It’s interesting to try to re-factor humor so that it’s not making fun of someone so much as making fun of the human condition.

OK, maybe I got a bit ranty there. It just really drives me nuts to have to watch these gomers in Washington act like they never had enough money to fix systems to be able to keep the Russians out and whining that they are going to get spanked again. Yeah, so now you know what I sound like when I’m pissed off.

I interview Fred Cohen (another old-school security guy) about “strategic security” for my column at Searchsecurity [ranum] Fred does a very good job of breaking the problem down from the top: start with your requirements, then your assumptions, then – and only then – think how to build a system that meets your criteria. Sounds simple. It’s not.

The election machines: it did not escape my attention that the states want to retain control over “their” election machines so that they can control “democracy” in case the outcome looks like the voters didn’t choose the candidate they were supposed to. That’s why George Bush beat Al Gore, isn’t it? Let’s accept that the two parties are both crooked vote-rigging bastards and let them do gerrymandering and voter suppression and all that stuff but for dog’s sake build some voting machines that don’t get demolished instantly at hacker convention hack-a-thons. [engadget]

I read “cyberkabuki” as “cyberbukakke”. I am not sure whether this says more about the situation or about me…

So. Still waiting for Gibson’s black ice.

cartomancer@#1:

I read “cyberkabuki” as “cyberbukakke”. I am not sure whether this says more about the situation or about me…

It says entirely good things about you, dear cartomancer.

John Morales@#2:

Still waiting for Gibson’s black ice.

Robert Graham referenced Gibson’s brilliant work in a rather crass commercial attempt to market it, circa 2000. Network Ice/BlackIce Defender.

It was actually not a bad product, except for the smell of credibility burning.

“Coats warned that Kremlin influence operations would continue for the foreseeable future, and that Russia’s next target is the 2018 midterm elections.”

So if the Republicans lose the elections they can blame Russian influence and try to get the results cancelled? And if they win they got what they want?

Anything to improve the US “democracy” is only going to hurt those in government, and especially the Republicans.

Australia’s elections still work via a pencil applied to paper, counted manually. Seems to work.

Yeah, that’s what we do in the UK too. Nobody (well, nobody worth listening too) seriously questions the integrity of of ballots cast at polling stations here, although there are some valid questions around postal voting… So, instead of “a networked vote collection system that cross-records votes using hashes so voters can verify their votes were tallied and that there are no ‘additional’ votes […] run[ning] atop a trusted operating system designed to TCSEC A1 target, with mandatory access control and a Ring0 kernel running on trusted hardware”, what you actually need are a lot of pencils and a bunch of civic-minded volunteers. Keep It Simple, Stupid.

Of course, here in the UK (and I believe in Australia too) the administration of elections is a non-partisan matter, which also helps.

@#5 and @#6

It’s the same in Latvia, paper ballots, counted manually. Except that voters must make their markings on ballots with a pen, pencils aren’t used. There are plenty of observers, so it’s not possible to stuff the ballot boxes with additional votes or to count the ballots incorrectly. So, yeah, it’s simple and secure.

I have heard some people asking for the possibility to vote online. In Estonia it has been possible to vote over the Internet since 2005, and some people in Latvia have said that we need this option as well. I’m not sure how secure Estonian voting system is though. During last Estonian parliament elections a third of all voters chose to vote over the Internet. If some hackers wanted to change the election results, tempering with one third of all votes could be enough to do the trick.

Dunc@ #7

It’s not civic minded volunteers, it’s local authority employees or bank tellers of sufficient standing who get a nice bonus for doing it. Back in the days when I worked for an LA it was considered a plum role even though being at a polling station was a very long day and counting the votes could be a very long night, a day off from your normal work, extra pay and at some polling stations, especially at local elections, nothing to do all day. People would read, knit, etc and essentially have a day off from the normal pressures of their jobs, but without having to do anything at home either.

Thanks for the correction, jazzlet. I don’t where I got the idea they were volunteers from…

Holms@#6:

Australia’s elections still work via a pencil applied to paper, counted manually.

Dunc@#7:

Yeah, that’s what we do in the UK too.

Ieva Skrebele@#8:

It’s the same in Latvia, paper ballots, counted manually.

I was specifically thinking (and referenced) a geniune American Voting Disaster in which voting machine ‘flaws’ threw the election from Gore to Bush. The US southern voter suppression strategy has long relied on throwing out votes that are ‘suspicious’ based on regions (code for: race) or names (code for: race) or gerrymandering. Having bad voting systems is a part of the southern strategy and has been since just after the civil war – prior to that, they had easier techniques.

Perhaps Latvia, Australia, and the UK don’t have this problem, or prefer to imagine they don’t. To a certain degree I suspect it depends on the balance of power – if things get close enough in votes that it’s worth “losing” or “finding” a few here and there, it’s going to happen.

Further, I am not recommending that improved voting machines are the solution to right now’s problem but we’re going to have problems with an election being outright manipulated, like it was in Florida, using the crappy voting machines that the states already have in place. We need to deal with that, and voter suppression and gerrymandering at a systemic level and it’d optimistically take a decade to get there. The US’ strategy seems to be “slip on banana peel, fall down, cry a lot” and that’s what they’re setting up for for 2018 and 2020.

jazzlet@#9:

It’s not civic minded volunteers, it’s local authority employees or bank tellers of sufficient standing who get a nice bonus for doing it.

And, in the south…

Of course, where I live there are no non-white people, so it is no suprise to go to the polling place and see nothing but Whitey McWhiteface working the polls. Unfortunately, that can be how it plays out in Georgia and Mississippi, too.

Marcus, @ #11:

Well, one of the other things our system has going for it is transparency – votes are counted in public, and the count can be observed both by representatives of all parties and by members of the public. Our ballot papers are simple, and since they’re counted by hand, we don’t have many of the issues that arise from using counting machines (of the “partially-filled bubbles” or “hanging chad” varieties). The process for throwing out or contesting any paper is open, and since the ballots themselves are simple, there are very few contested ballots – almost all “spoilt papers” are very clearly deliberately spoilt. We do occasionally run into issues when there are multiple different ballots using different electoral systems happening on the same day, but even so, the number of spoilt papers usually remains quite low. And since the whole process is watched intently at all stages by both partisan and neutral observers, it’s very difficult to lose any ballots, never mind enough to throw an election.

Oh, and we don’t have people waiting in line for hours to vote, either…

Moving away from the question of voting, this may be of interest, and more relevant to the wider point you’re making in the OP:

In other words, most federal agencies have IT security that makes a sieve look watertight…

Dunc @#12:

Oh, and we don’t have people waiting in line for hours to vote, either…

And, not so much with the KKK standing around polling places with guns. Nowadays, we have ICE, and they don’t wear those goofy white hats. But it’s the same shit, different day.

In other words, most federal agencies have IT security that makes a sieve look watertight…

“You have a sieve!?!?! Oh, maaaaaan, I wish we had a sieve! We could use it for a boat!”

Terrifying, isn’t it?

48.5 per cent report employees jailbreaking their work devices.

It’s like a distributed Edward Snowden, for every desktop…

The other thing I wonder is: how many people answered those questions with “I have no friggin’ idea…”

Dunc@#14:

The other thing I wonder is: how many people answered those questions with “I have no friggin’ idea…”

“I trust Apple. They have a good story on security. And I trust the cloud, right? I mean, it’s all OK, right? It’s in the cloud. And it has encryption. See the little lock icon?”

I have voted in the US and in Sweden. (In Sweden, long-term non-citizen residents can vote in local and regional elections.) Here in Sweden we vote on paper, and my experience here might transfer to Latvia, Australia, and the UK.

In the US there may be several elections each year. In addition to presidents, governors, state and federal senators and representatives, mayor, etc. we also vote for judges (or vote to keep judges), auditor, secretary of state, members of the Public Regulation Commission, and more. We also vote to issues bonds, modify the state constitution, and much more. A ballot can be several pages long. And I never understood why we in New Mexico vote for the county surveyor, nor felt competent enough to decide.

In Sweden we vote once every few years, for the party to represent us in the local, state, and (though not for me) national elections. There are three envelopes, one for each race. In each one goes a ballot for the party I am voting for. On the ballot is a list of names, ordered by how the party would like them to be in office. If they only get one member elected then the first one goes in, if two members are elected then the first two. I can leave the ballot blank, or vote for specific people, which the party may affect how the party chooses who gets the position.

This is far easier than the US. I think part of the reason for machines in the US is a response to the complexity of our ballots.

The US system resulted in effectively only two political parties. In Sweden there are 8 political parties in the national parliament.

Perhaps Latvia, Australia, and the UK don’t have this problem, or prefer to imagine they don’t. To a certain degree I suspect it depends on the balance of power – if things get close enough in votes that it’s worth “losing” or “finding” a few here and there, it’s going to happen.

No, I’m not imagining that there isn’t a problem, I know that. Here cops don’t shoot people, healthcare is affordable and election fraud doesn’t exist. Not every country is as shitty as USA.

-Anything similar to gerrymandering cannot exist, because election winners are decided based on who gets more votes. It’s irrelevant where each voter lives.

-In Latvia most people don’t have a driver’s license; instead every citizen is required by law to have a passport. Everybody has one and passports are what gets used as identification in the polling stations.

-Voter coercion is impossible. Voters choose and mark their ballots behind a curtain. All forms of advertising are illegal on the election day. If somebody even attempted to stand in the vicinity of a polling station and pester voters, they would get arrested.

-Ballot box stuffing is pointless. When people enter the polling station, they are counted. The number of envelopes in the ballot box must match the number of voters who showed up.

-There are a lot of observers everywhere at each step of the election process.

-Any member of the public who happens to be paranoid (or bored or curious) can show up and observe the election and vote counting process. In my first debate club we had a guy who had done that. I discussed the vote counting process with him years ago, so I have forgotten the details from that conversation, but his conclusion was that it would be impossible to fake the results.

-We have approximately 20 political parties participating in each election (at the moment we have 6 parties in the parliament). The probability that all those people who are in the room where votes are counted will all conspire to promote one and the same party is pretty small. Besides, if any suspicions arose, other political parties could just send their members as observers.

-Ballots are simple, straightforward and foolproof. It’s impossible for a voter to accidentally spoil their ballot. All ballots that don’t get counted are spoiled intentionally.

-Elections are on Saturday, there are a lot of polling stations, so no voter needs to travel far to cast their vote, waiting in lines never takes longer than a couple minutes (I think my record for the longest waiting time was about 5 minutes, usually there is no line at all).

-We have elections once every two years. And occasionally we also get referenda. So it’s not obnoxiously often.

No; in Australia the process is independent of the Government of the day.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Electoral_Commission

http://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/counting/index.htm

Ieva Skrebele@#8:

Do these answer your question?

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2017/09/security_flaw_i.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infineon_Technologies#Security_flaw

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ROCA_vulnerability

To be fair, voter fraud is probably as old as voting. Classical Athens had its share of attempts to game the democratic system, although since it was a direct democracy they aren’t directly comparable to what happens now. Athens relied not on election for the vast majority of its public magistrates but on sortition – citizens’ names were selected randomly, by lot, for the ten Archonships, the 500 council positions on the Boule and various other civic offices. For one year only, of course, then completely different people were chosen. And for most of the roles you couldn’t serve more than twice in a lifetime, and not within a certain number of years either. We still use a similar system for juries today. The Athenians selected their jurors by sortition as well, but their juries were vast – at least 200 people, sometimes as many as 1500 – and the jury was the final arbiter of all legal matters, there were no judges in the Athenian Dikasterion.

The only positions the Athenians felt there should be actual elections for were the strategoi – the generals – and the heads of the boards of treasurers, the apodectai and colacretae, because military and financial skills were considered a specialism that not everyone would have. Everything else in the government and civil service was thought to be the common share of every citizen. Ostracisms were also conducted by ballot – you wrote the name of the guy you wanted gone on a potsherd and dropped it in an urn. The guy with the most downvotes, assuming the quorum of 6000 had been reached, was kicked out of Athens for ten years, no questions asked.

Voting in Athens was generally done by a show of hands, and there were special tellers appointed to adjudicate the result (which could be challenged and the vote re-done if someone complained). The general trick was to have all your supporters stand close together in clumps, so their show of hands looks more impressive amid the crowd on the Pnyx where votes against will be spread evenly throughout.

When they used ballots, however, – in the form of potsherds on which the candidate’s name was written – then the fraud could really begin. We have a collection of custom-made mass-produced potsherds, ready-inscribed with the name of the controversial general Themistocles, that were found at the bottom of a well on the Acropolis. They were presumably produced in readiness for his ostracism vote (472/1 BC), all 200 or so written in only 14 hands. Of course, it may just have been that they were produced for illiterate citizens so they could still cast a vote, or as a practical measure because Themistocles was very unpopular in certain circles and they didn’t want a queue forming round the voting urns as people scratched his name into their bits of broken pot. We have anecdotes from historians telling us that getting someone else to write the name on your sherd was quite common if you couldn’t write – in one case a man turned to his neighbour and asked him to write the name of Aristides, because he was sick and tired of Aristides being hailed as the most just and upright man in the city. His neighbour turned out to be Aristides himself, who dutifully wrote what the man asked and handed it back, proving his claim to the reputation.

I think we’ve improve a bit in terms of voting technology by now. Though I do think we ought to bring back ostracism.

# 6 Holms

Same in Canada. Ballot + pencil. But I think the US votes for everyone from president to dog catcher on the same ballot.

@ 7 Dunc

here in the UK (and I believe in Australia too) the administration of elections is a non-partisan matter, which also helps

Same here in Canada. Federally the Chief Electoral Officer is a Parliamentary Appointment not government appointee.

@9 jazzlet

I am not sure what country you are from but in Canada we have official staff and (assuming the party can muster the bodies) certified party representatives who may observe the vote and the count and may challenge a vote if they disagree with the official’s determination.

One would almost never use local authority employees as it would seriously annoy the local authorities if you poached them.

An awful lot of senior election staff at the poll level look like seniors. Which may explain how efficiently elections work. These women are good. Apologies, there may be some men too at the senior level.

Concerning the media. My quick scan suggests that your reporting on a corporate product. Do you ever watch RT.com? Aljazeera? Examine campaign financing? (I think the purchase of congress was described in chapter nine , “The Rich and the Super Rich” by Ferdinand Lundberg. )

jack16

My quick scan suggests that your reporting on a corporate product. Do you ever watch RT.com? Aljazeera? Examine campaign financing?

With regards to internet security, I was reporting off the top of my head from memory. My main daily news sources are The Guardian, Al Jazeera , RT, and The Washington Post. I still watch the New York Times but I consider it more like a “scope onto a certain part of the partisan process.”

I have not read Lundberg; I don’t think that congress was ever purchased, really – it was constructed as an oligarchy all along.