This post almost certainly will not be as well-organized as I wish it could be. I feel that the topic is of great importance, but I am unconfident of my ability to organize an argument, and I am painfully aware that I know far less about the topic than I ought to. Consequently, I welcome dismissive comments as well as substantive ones – part of what I need/want to do is learn more about the topic, and I’m having trouble even figuring out where to start. This will all become clear in a bit, I hope.

I absorb a lot of documentaries and such on youtube and in audiobooks, and have recently discovered that some part of my subconscious seems to be listening even when I am not fully awake. Time unspools, but my brain is still picking up and ordering signals and sometimes something triggers some alert mechanism (“boss, you’re really going to want to hear about this!“) and then I am wide awake. Other times, I encounter new things thanks to podcasts like the amazing “In Our Time” (BBC) with the amazing Melvyn Bragg. For example, I learned about Doggerland thanks to [BBC] and spent several weeks reading up on the topic and enjoying the feeling of having my mind blown. [stderr on Doggerland] So, what woke me up was something coming across on youtube auto-play, and suddenly I was awake because there was discussion of a mesolithic temple, the earliest temple ever identified. Normally, I do not give a shit about temples – they are just monuments to stupidity – in this case there was something else going on.

(Stable diffusion and mjr)

The show I had stumbled across was a piece on a place I had never heard of, and what triggered my wakefulness was something like “(mumble) 11,000 years old, that’s, uh, older than Sumer…” I think that my subconscious thought that someone had found a temple in Doggerland (16,000 – 9,000BCE) or something like that. But, no, it was about a place called Göbekli Tepe and the title was “The First Temple on Earth, 6000BC”. I have a link to the documentary at the bottom of the post, along with some of my other sources that I have ingested since then. [And if any of you have a reference do a definitive/canonical source on the topic, please share it in the comment section!] The description of the place, and the pictures I saw later, are fantastic. The description is of “huge carved megaliths” which resonates in my mind with Stonehenge and the many dolmen in France that I played on as a kid. This is amazing stuff:

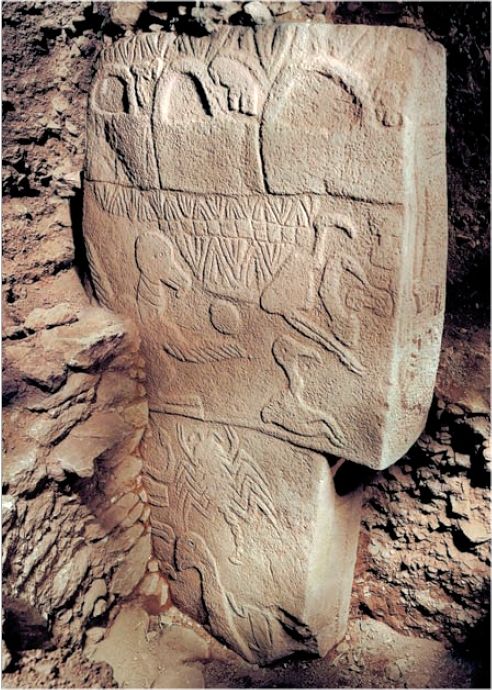

[source: researchnet]

The world’s oldest monuments may soon get an image makeover. A new project will promote and preserve Göbekli Tepe, home to the most ancient temple structures ever discovered.

I was still 1/4 asleep, started bookmarking things, then slipped back off into lala land, my mind whirling with fragmentary ideas.

[source]

[Sci News]

“The layout of the complex is characterized by spatial and symbolic hierarchies that reflect changes in the spiritual world and in the social structure,” Haklay said.

So the next day I started reading that sort of stuff, and the National Geographic piece and something started nagging at me, bigly. First off, there’s the bit about there being some inherent geometric relationship in the buildings, which didn’t seem like an argument. If you build 3 circular things that are together and more or less the same size, they will form an equilateral triangle. No big deal. Also, the structures are built on and partly into bedrock, so the geometry of the place is going to be somewhat limited by its size and the ease of constructing what, where. I don’t see this to be a huge big deal, though – there are lots of circular forms in the ancient world because roughly circular things are …

Wait, what’s all this stuff about temples and spirituality?

Alright, so there’s a lot of carving and so forth on the rocks that formed the interior. And I have to say I am quite amazed by it. What amazes me is that the stones and carving pre-date the propagation of flint (AKA: “hard rock”) so the carving and stone-work would have to have been done with the same limestone that was being cut. I.e.: the carving was mostly a matter of “bashing two rocks together.” But this place was occupied for thousands of years. Or, more precisely, “in use” for thousands of years. Here’s more completely mind-blowing stuff about Göbekli Tepe in case bashing rocks with other rocks for thousands of years doesn’t blow your mind: apparently it exists at the juncture between hunter/gatherer lifestyle and agriculture. I’m not entirely sure how this is determined, yet, but apparently Göbekli Tepe went out of use and was buried by shifting dirt (possibly also deliberately) and there aren’t signs of things like animal pens, etc. Apparently archeologists are pretty sure that the region was rich enough in wild crops and animals that a small civilization could live off the land, sending hunting and gathering expeditions forth from their encampment on the hill, to collect stuff and store it for a while…

… Which brings up what may be the most mind-blowing part (for me) about Göbekli Tepe: it could be that the transition to agriculture didn’t happen because some wise-ass realized that you could re-seed wild plants, or breed goats – it could be that the transition to agriculture was a result of the invention of storage. What if a tribe of hunter/gatherers began to realize that they could set aside enough stuff to comfortably provide for them over a winter? Well, it would be too much stuff to carry around from place to place – you want to set it down and leave it somewhere. Then you go forth and collect more goat meat, or whatever. And eventually you notice that the natural grains do grow in the same place year after year as long as you don’t tromp all over them. It’s an interesting idea. I don’t know how we’d be able to determine if that was what happened, or not. What if there was a trail down to where a wet area was, and 16,000 years later there was still a worn pathway? I can see the tremendous difficulty in figuring this sort of thing out without evidence in the form of artifacts stacked conveniently in strata in a garbage dump (I won’t call it a “midden” because that reminds me of my storage closet) That all comes from [GÖBEKLI TEPE – what happened in the 10,000 years before? | Göbekli Tepe to Stonehenge podcast #1] [There is an audio version and a video version linked below] I was like a happy dog rolling on my back in the sun, listening to this stuff as my belly fur heated – there are so many amazingly cool ideas in it that had simply never occurred to me.

For example, they go into an aside about flint and the flint trade. It hadn’t occurred to me (duh!) but of course flint was the valuable military and social technology of its day. According to them, there are relatively few examples of flint cutting implements prior to 12,000BCE but by 10,000BCE flint was everywhere. Like, literally, flint from one place was found 750 miles away from its origin – obvious signs that a flint trade had emerged relatively quickly, in a mere 1,000 years or so. They also argue that (“Hey, Thag say you haul that pile of rocks now.”) flint trading implies sea-based trade, i.e.: the invention of boats, and that is bolstered by tuna bones starting to appear in middens around 11,000BCE. Since you pretty much can’t catch tuna without a boat, we have a pretty good rough estimate of when sea trade kicked in, and it’s suddenly a lot easier to haul flint around. One of them also mentioned an idea I found hilarious, which was that there were some flint stashes found – obviously some flint merchant, or flint-hoarder, or napper had a pile of valuable flint which suddenly dropped in value (like any tech stock would!) when bronze started to appear. Bronze is such superior stuff that it would have spread rapidly along the trade routes because of its military value. I wonder if it’s possible to identify the onset of bronze by the increased sharpness in stone carvings that can be achieved with a bronze chisel instead of bashing rocks together? Bronze may have been too valuable for a while, for such a quotidien purpose; it’s for carving up your neighbors, not rocks.

Now, I start to get a frisson of concern: [archeology.org]

In 2006, after a decade of work at Göbekli Tepe, a team led by German Archaeological Institute (DAI) archaeologist Klaus Schmidt reached a stunning conclusion: The buildings and their multiton pillars, along with smaller, rectangular structures higher on the slope of the hill, were monumental communal buildings erected by people at a time before they had established permanent settlements, engaged in agriculture, or bred domesticated animals. Schmidt did not believe that anyone had ever lived at the site. He suggested that, in the Neolithic period between 9500 and 8200 B.C., bands of nomads had come together regularly to set up stone circles and carve pillars, and then deliberately covered them up with the rocks, gravel, and other rubble he found filling in the various enclosures.

I’m sorry, professor, but that is just daft. Schmidt, by the way, is the archeologist responsible for the meme that Göbekli Tepe is a temple or some kind of “monumental communal building.” I agree that is a stunning conclusion, though. Now, I feel like I have to go way out of my depth and propose a completely different set of hypotheticals. I know, I know, this is a great example of “arrogant software engineer way outside of his field” but it’s not like I can hurt my reputation significantly more than I normally do. So let’s go there.

From my 2004 vacation in Ireland:

[mjr, 2004] Loher Fort (cashel) Kerry

(mjr, 2004)

That’s … a parapet. It’s a simple and clever design, too, since it allows a defender to choose how much of themself they want sticking up over the wall at any time, and it also serves to make the base of the walls triple thickness compared to the thinner points which (if someone managed to pull one down) have a defensive parapet right behind them. In the case of Loher fort, it’s pre-firearm so the fact that there are hills looming over it is not a big deal – the locals did not expect to be attacked by Romans and, if they were, they’d just lose quickly. Loher is a fort that a dispersed clan of farmers can run to in time of need, because they were living in a raiding culture and raiding is what happened. The fort being made of stone means its upkeep is negligible, it doesn’t need to be enclosed since it’s not intended for long-term inhabitation, etc., etc.

By now, you see where I am going. It is impossible for me to look at Gobekli Tepe and see anything but a fort. I’m going to hammer on that point for a bit, though I think it’s hardly necessary. It’s hard to imagine a hunter/gatherer civilization, but … what would that work like? Well, you’d want a place to store stuff and a place to come in out of the rain. You’d want to be able to keep an eye out for raiders – other hunter/gatherers who want to gather your gatherings. So, you’d build your fort on the top of a large hill, so you could see in all directions but – equally importantly – your people could see it. I’m imagining that if a large group appeared in the distance heading toward the fort, you’d holler or blow a horn or bang a drum and everyone would come running for the defensive perimeter. That would, generally, do the trick – I would not expect a typical hunting party to see a stone fort with people on its walls and decide that attacking was an appealing proposition. For a hunter/gatherer party, a severe injury almost certainly means death or a long, painful limp back to wherever the hunting party is camping.

When I was listening to the “First Temple on Earth?” video, one of the things they mentioned as impressive, aside from the “megaliths” was the “large bench around the interior of the central chamber.” That’s not a bench, that’s a parapet. And the “megaliths” are, in fact megaliths, but they are also “roof supports.” I feel I’m going a bit out on a limb here, because none of the archeology podcasts I have consumed so far appear to have figured out that the tops of all of the megaliths are the same height, except for the central ones that are a bit taller to give some pitch to a roof? Is this not obvious?

[Source: National Geographic rendering of what building Gobekli Tepe might have looked like]

The “megaliths” are roof supports for a sloped wooden roof (probably thatched?) and they’re engineered to stand proud of the top of the wall, so there’s a) ventilation and b) a place for the archers and spearmen on the parapet to fuck people up. I am not sure to what degree the National Geographic artist drew from reality (they are usually very careful) but there’s even a visible reinforcement by the roof supports near the “kill zone” where the entry passage debouches. Next, there is a parapet around the inside of the curtain wall, too, so whoever’s holding the kill zone at the entry passage can retreat if pressed and suddenly the attacking force is taking it from front and above. Spears are horrifically effective for that sort of defensive work, and we are assuming that the defenders are hunter/gatherers who have put in their time spearing goats or rabbits or whatever.

It’s not a fucking temple.

Sure, there are other rooms around it, and it looks like they could be defended separately or if the attacking party was large, everyone could fall back to the central redoubt. I have not the archeology skills to know if there is some way to determine approximately when which of the structures was erected but I bet it started off with one pretty good central fort, entry way, and keep and, when the tribe was able to successfully defend itself and survive, they built a few more. They built them close enough so that, if you were attacking one of the forts, the archers in the other fort would be shooting arrows into your back the whole time.

Sure, it has decorations – I’m going to venture the point that humans, even when all they had was, literally rocks to bang together, decorated them. Why not, if you’re already shaping big rocks, may as well, it’s incrementally small effort. But I think we should avoid the conceit that humans only do art for religious or ceremonial reasons. Sumerian and Babylonian art, which is basically “King Thag laid the fucksword of waste to these people and you don’t want to be next.” Is that “ceremonial” or “political”? I don’t know if there is a difference. Perhaps it has decorations because whoever was in charge of construction told the construction workers to decorate it, while they were at it.

Remember what I mentioned earlier about the theory that storage led to agriculture? There are outbuildings near the fort, smaller constructions with megalith roof supports similar to the fort’s. I have a little trouble with archeologists’ assertion that nobody lived in the place because a village and storage places around a fort is a very, very ancient architecture that has been invented and improved on over and over and over.

Now, let’s talk about the elephant in the room. I think that the archeologists, who are trying to claim a ceremonial purpose for the place, are playing a bit naive, given what we know of human predilictions and behavior. Hunter/Gatherers would inevitably engage in trade or conflict when they moved into new areas. As soon as hunter/gatherers became hunter/gatherer/storers, they would inevitably engage in trade or conflict with anyone who was looking hungrily for a supply of dried goat meat that someone had stored against a harsh winter. Raiding and conflict and casualties inevitably bring in captives, and what does one do with those? One has them haul stones and erect megaliths, etc. The National Geographic illustration is thought-provoking in that it shows a population of about 50 people working on building walls and hauling rocks. If you have one hunter/gatherer supporting the material needs of one rock-hauler, you have a pretty sizeable settlement. I’m going to go out on a limb and predict that the rock-moving was mostly done with slave labor. If you give anyone a choice between hauling multi-ton rocks and bashing rocks together, or picking raspberries or hunting rabbits, I can’t imagine choosing the rocks. Unless a hunter/gatherer civilization was totalitarian (as I suspect they tended to be) ruled by an iron-handed monarch, someone could presumably just wander off, if they didn’t want to break rocks.

In the case of the Egyptian pyramid-builders, there was an entire imperial economy paying for it, and an agricultural system building up a surplus that could be used to pay for labor. And, even then, the pyramid-building workforce was not entirely volunteer labor. If we’re looking at a civilization that was sitting on the transition-point between hunter/gatherer and farmer, maybe what happened is that part of what drove that change was the need to store up enough excess goods that they could have a slave labor pool to build forts. I know that’s a dark view of humanity but I think we should be clear-eyed about humanity’s past and not fool ourselves into thinking that these massive structures were built by hunter/gatherers who took a few years off gathering, started singing “kum ba ya” and engaging in extremely high effort, low value construction. It only makes sense if it was high value construction (defense) being done by supervised labor. A corvee (institutionalized periodic forced labor) only makes sense if you have enough of an economy that your civilization can coast for a period while no provisioning labor is being done. What if seasonable labor on fort-building is what caused the shift to agriculture?

A more palatable (but less likely) scenario is that hunter/gatherer civilizations flickered out when agriculture took off, and the farmer civilizations could field armies long enough to lay siege to hunter/gatherer redoubts. How long would Gobekli Tepe be able to hold out, if the inhabitants were hunkered down behind their walls, while invaders ate their goats and berries, and the produce that they brought with them?

I like the fact that archeologists and anthropologists seem to want to put a nice spin on things. Yes, I know that’s not always the case (I’ve read Napoleon Chagnon) but it seems to get in the way of understanding what they’re looking at.

It is not necessarily the same people who made the carvings, and who covered them up.

Gobekli Tepe – how could you bring that up without mentioning 11,000 year-old carving of man holding his penis

I don’t know anything about the design of either forts or granaries so I won’t make an attempt at your central idea.

Reginald Selkirk@#1:

Gobekli Tepe – how could you bring that up without mentioning 11,000 year-old carving of man holding his penis

I forgot. The Prehistory Guys’ podcast touches at length on our carving of the fellow touching himself, referring to it as “holding one’s bits.” Apparently it is a very common theme. I actually fired up stable diffusion and had it do some cave art of hunter gatherers holding themselves, but it didn’t come out so great. Then, I developed a short tale about King Thag and had stable diffusion illustrate it, which was slightly better.

“The death of King Thag” – the queen gets mad at Thag and sends her cat, which kills him

I hate to ruin the discussion, but there’s also a huge amount of nonsense out there about Gobekli Tepe from the ancient astronauts crowd. That’s where I first heard about it, at a conference where the loons had a goofy great presentation about star symbols and alignment and landing pads and such crap. I think Graham Hancock has also dragged Gobekli Tepe into his absurd theories.

PZ Myers@#3:

I hate to ruin the discussion, but there’s also a huge amount of nonsense out there about Gobekli Tepe from the ancient astronauts crowd.

Ohhhhh, goddddddd….

I did a few renderings of the aliens helping build stonehenge but I didn’t think they’d fit in my posting. PS – the aliens had a habit of ritually holding their bits with their free hand. All the statues of humans holding their bits are references to the aliens.

In the prompt, I used the phrase “D-beams flickering” for extra credit

So, now, joking aside, that means that trying to contact any of these archeologists to tell them “it’s a fort not a temple” is going to meet a ton of crank defenses raised by the ancient astronauts crowd. Maybe I’ll just leave it at this.

There are identical structures on the Atlantic coast of Scotland which are called Brochs. There is no consensus on their purpose.

There is a settlement called Boncuku Tarla east of Gobeki Tepe which is considered to be the same age.

There is also Kerehan Tepe in the same area north of the river. Tepe itself means hill, and much of the hill is composed of multiple layers of the same circular structures which were buried and then new structures built on top.

Settlements have hearths, possible charred grains and animal bones, pottery shards, and lots of flint fragments as evidence of occupation. None of those things are found at Gobeki. This area was much wetter at the time, and there would have been extensive reed beds along the river. Wheat and flax are both native to this region.

I’ve seen the theory that these complexes had a funerary function, with bodies exposed for carrion birds.

Perhaps those shelves held ancestral remains. Stone Age people did many things with bones and bodies. Burying Grandma under the floor was surprisingly common.

The central pillars have arms carved on their sides.

The one that you posted is illustrated with a dismembered corpse along with several identifiable species of wildlife.

A vulture has the head, the wood stork has the penis, the other vulture head has the legs, and a sand grouse has the torso on the lower panel.

I would agree that it’s a monumental communal structure. It obviously took a group of people to quarry those pillars and then erect them. What they used it for is still unknown. There is no evidence of warfare like burning, or concentrations of broken projectile points, so defense doesn’t seem its primary purpose.

Marcus, you’re in the wrong century here. «It has walls, so it’s got to be a fort» is the 17-1800’s style of archaeological hot take.

Hey Marcus, long time since I last wrote. These ancient sites are simply amazing!

But I disagree with your conclusion what it is. People are differing there, I think Schmidt and others have a point. When you look at the terrain (vid below), the fort idea is not as clear cut as I read your post. There is/was nothing to defend. You wall in things you want to and *can* defend. But it is an open visible place, what else would you do there other than to meet and “have rituals”. If you are a mobile people, you could just leave and come back later. I think, we have a cultural “settler mindset” and have trouble thinking past “holding terrain” sometimes.

The youtube channel Miniminuteman made four very good videos about Göbeki Tepe and surrounding acheology sites like Karahan Tepe.He talks aboubt the different ideas what it actually is, and wehen you see the lay of the land, several approaches make sense.

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJU973IbG7I)

@4:

I wouldn’t know anything about D-beam flickering. Could be a power supply problem. I am still using C-beams, which as everyone knows, glitter; especially in the dark.

I ran across this:

Boffins suggest astronauts should build a Wall of Death on the Moon

Have you considered the ‘handball court’ explanation?

Somhow I only posted part of my comment, copy/paste mistake. Sorry about that! Here is the other bit.

You wrote:

“Unless a hunter/gatherer civilization was totalitarian (as I suspect they tended to be) ruled by an iron-handed monarch, someone could presumably just wander off, if they didn’t want to break rocks.”

“Totalitarian” leadership styles are hard to maintain a a smaller group of people where, that could just go away and leave you sit there without any workforce. Or you know, just kill you if you are too much of an ass. Hunter gatherers work different from our current culture.

I also think you underestimate the desire of humans to do shit for doing shits sake. Ask a mason, how they think about rock breaking (Or to be provocative: “Who in their right mind works with glowing hot metal and then whacks it with a hammer all day? That’s fucking DANGEROUS! Why not have the slave do it?” Yet you are a blacksmith and (deservedly) proudly post about the cool objects you created). It is a hill along the way grazers took ten thousand years ago, where rather easily breakable stratified limestone rocks outcrops. These structures are big structures, but not *that* big, these are things that can be made by communal effort over a longer time. There probably was no foreman and a timetable to “get this thing done before King Xelon Of X has shuffeld off this mortal coil”. Just the act of working together can be a huge social force.

“That is the place where our mothers and fathers met with others and errected a stone. They told us in their stories. This year WE will meet with others, WE will errect another stone. And we will tell stories to our children, so in the future other people will come and errect their stone and tell tales.”

You jump to warfare as a reason to build something. As a fellow wargamer, that way to often also thinks ’bout conflicts, I ask you these questions: Look at the layout, is that really a fort? Is that really a defensive architecture? (The ireland parapetry: yes! They have acessible walls, stairs. And no real artworks, all just very small rocks.)

How would you defend Göbekli?

If you do like to keep your dark view on humanity: We have no idea what these “ritals” were. Might just as well be of the blood-and-skulls type.

This guy (archaeologist etc) talks about the site and also about Karahan Tepe. It does sounds like the site may have had some sort of ritual significance but it also sounds very complicated. Here’s a link to the first video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJU973IbG7I

Ooops someone beat me to it and posted while I was writing!

I did a little research on the tool finds from Gobeki and some of the other sites that are part of the Taş Tepeler culture. This is pre-pottery, with fired clay figurines and beads appearing in later eras of occupation.

Stone vessels and grinding stones were found in abundance at Gobeki. Maybe they were having seasonal brewing and feasting parties while they made and installed the stone pillars?

Photos of both at the link.

https://www.archaeology.org/issues/422-2105/sidebars/9715-gobekli-tepe-tools

At the settlement site, numerous stone labrets were found in graves.

https://arkeonews.net/archaeologists-unearthed-the-earliest-known-evidence-of-body-perforation-in-skeletons-dating-back-11000-years-at-the-boncuklu-tarla-in-turkiye/#google_vignette

Marcus (and anyone else who might be interested), please read ‘The Dawn of Everything’ by David Graeber and David Wengrow. It is a mighty brick of a book (I read it little by little while riding the bus for my daily commute, and I slightly injured my wrist from holding it up), but in contrast with several other ‘big picture of humanity’ type books, the authors are an archaeologist and an anthropologist, and actually know what they are talking about.

They discuss how in many places around the world hunter-gatherers constructed monuments of various kinds. They also counter the notion of ‘agricultural revolution’ – in their view people went a long time (many centuries, maybe a couple of millennia) being hunter-gatherers who also played at some level of agriculture on occasion, or somewhere between gathering and growing plants – for instance shaping the landscape to favor preferred food plants. They discuss slavery in foraging societies (eg in the North-American Pacific Northwest), and how other relatively nearby societies (eg coastal California area) deliberately took measures to design their culture to minimize the inequalities that allow slavery to come into being as an institution.

A number of disparate thoughts.

1. The structure may have served different purposes at different times or even at the same time. Especially likely if it saw use, continuously or on-and-off, over thousands of years.

2. Another structure that puts an elevated “parapet” or steps around the inside perimeter is … a stadium, or auditorium or similar. The steps/parapets could have been audience seating for performing arts or sports taking place in the center, where they would have a good view. (Any indications or estimates of what the acoustics would have been like, presuming either an open top or a thatch roof?)

3. In most places, there are intervals each year when there is little or no provisioning labor possible; at this site there was likely a significant winter each year, and even tropical sites (e.g. Egypt) often have dry intervals that lie outside the main growing season. Hierarchical societies will want to keep the laboring classes busy 365/7 since idle underprivileged people might spend the time organizing up a revolt otherwise (see also: why after the 2020 BLM protests got huge the ruling class suddenly became very focused on getting everyone back to normal work schedules, pandemic be damned). In non-hierarchical societies, people will work toward the common good and may well divide less desirable tasks in a fair manner, such as by round-robin assignment or designating certain times or days of the week etc. by mutual assent. Do you have a regular day on which you dread doing, and then do, laundry, by any chance?

People also *want* to feel useful and like they are contributing, as well as getting plain ol’ bored during enforced idleness. So, during winter they might have put work into other things while provisioning simply was not an option. Quarrying and moving stones might actually be easiest then, as it is far easier (and safer) to do heavy outdoor labor in cold weather than in hot, and it is far easier to move heavy loads over snow than over mud. Picture those stone blocks on large sledges with big flat bottoms, being hauled by a team of people decked out in parkas and snowshoes. Once the sledge is moving it would not be very hard to keep it moving (avoiding being run over by it when going downhill would be a bigger challenge, as well as cornering). In early spring, with the snowpack gone and the ground soft enough for digging but before the growing season/gathering season, then would be the ideal time to use the assembled raw materials to actually build (or add to) the structure.

In short, both labor and transportation activities likely varied seasonally here and at most ancient sites. Our modern insistence on doing basically the same thing all year round, rain or shine, snow or drought, is historically atypical and only possible because of modern technology. Even then it is suboptimal — consider how we use brute force (enabled by oil’s energy density and abetting climate change as a result) to mass-shovel the roads clear of snow all winter in the north so we can keep using the same cars and trucks all year round, instead of switching to car-snowmobile and truck-snowmobile vehicles of some sort for half of each year that are designed to go overtop of snow rather than on pavement. Most likely this is a temporary phase before we find ways for industrial civilization to work more harmoniously with the seasons and with sustainable levels of resource consumption. Our descendants will likely be using different vehicles at different times of the year, mostly efficient and electric ones, for land transport, and electric dirigibles for air transport that isn’t particularly latency-sensitive, reserving (electric!) heavier-than-air planes for the latency-sensitive stuff; and at sea, a second age of sail with electric backup motors for maneuvering in port and for getting out of becalmed conditions, again for everything not too latency-sensitive.

As for the purpose of the structure? If it wasn’t defensive, did have audience seating, and also had images of scavengers consuming the dead, then maybe … funeral parlour?

Some things only look bad when you know there is an alternative. I think slavery is more or less inevitable in any human society that has not yet developed the technology to build an engine capable of turning fuel into kinetic energy.

An egalitarian society dependent only on muscle power is not altogether impossible, but it would be highly unstable. It would only take one person who has both limited empathy and a sufficiently persuasive way of speaking to get into a position of power, conduct a few demonstrations of what is possible when you force people to work hard, hand around some fancy trinkets as a convincer; and suddenly the idea of enslaving someone would begin to gain popular support (closely followed with ideas of who to enslave). Such a society also would be vulnerable to a hostile takeover by any other, less-egalitarian society that had managed to overcome both the aversion to coerced labour and geographical separation from its neighbours.

I think meat eating, too, might be more or less inevitable in some parts of a human society without certain technologies. We need between 6 and 10 MJ worth of food each day just to live an all-mod-cons Western lifestyle; and every Joule consumed by a motor in an appliance we use in the course of a day would otherwise have to be added on to that amount. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it is not at all difficult to get at least that much energy purely from plant sources if you can drive a car to a supermarket and buy refined foodstuffs; but how likely is it that a low-tech society would have a reliable, year-round supply of forageable food, that they would not exhaust without it reseeding itself; even if we neglect the fact that modern staple food crops have been genetically altered to deliver more J/kg than the wild plants from which they are descended?

(I can see in this the bare bones of a sci-fi plot wherein an advanced civilisation with many shameful dead-end mistakes under its belt seeks out small planets with the right sort of conditions for civilisation to emerge, and carries out some “pre-seeding” by strategically placing artefacts in the specific hope that the societies that do eventually grow up there will develop engines and refined food early enough never to become reliant on slavery or meat …..)

My understanding (very limited) understanding of Gobekli Tepe (probably not a lot more than Graeber & Wengrow + Miniminuteman’s Youtube + Tides of History Podcast), is that there is insignificant evidence of consistent long term habitation around there to say it was part of a continuously occupied site. So, you know, hearth sites are typically reused repeatedly if you stay in one place, stones get moved around to frame the edges of (otherwise biodegradable) shelters, middens build up in single locations. All these leave pretty solid archaelogical traces which just aren’t there when people gather in large numbers but don’t settle – i.e. the hearth locations move, the middens are all pulled apart by scavenging animals, shelters aren’t reinforced.

So, the appearance of a complex megalithic site without evidence of permanent settlement and evidence of social stratification (small houses and small people, big houses and big men. Because they’re always men) is kinda a confounding factor to the idea that everything big and complicated needs a permanent class system to establish it. See also Cucuteni-Trypillia culture https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cucuteni%E2%80%93Trypillia_culture, which has evidence of mega-sites https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maidanetske, without social stratification.

This leads into other interesting ideas about early forms of social organisation, coercion, power, labour and mobility.

It looks like for a long time, people could just, well, walk away. I think there is good evidence from the Cucuteni-Trypillia sites + other Neolithic-Chalcolithic cultures that mobility was probably higher than it is nowadays. Like, you almost certainly moved away from your family. I mean, it makes sense that e.g. river valley civilizations like the Nile and Mesopotamian civilizations could centralise power, locate and restrict people and enforce debts, obligations, power, religion, family, because, seriously, where you going to go. Upriver, or, downriver. Or into the desert to probably die.

Of course, it turns out that if you do enforce things like debt, ownership, slavery, serfdom, obligation, and other forms of power, well, your society is very effective at eating up anyone else around you. So, we live in a world now where we readily project back the dog-eat-dog and survival of the fittest kind of mindsets, because that has become common sense. And valorised in our religions, and so on. I mean, Catholicism is basically Roman jurisprudence elevated to divinity (wait, hang on, Roman jurisprudence was basically considered divine anyway … sooo …)

But honestly, if you are a power hungry narcicist who fancies himself or herself the most important, well, you have to sleep. And in small mobile societies everyone can just go away while you sleep. Or make you go away.

I entertain myself and keep myself sane by imagining what 2000 years from now will look like. So, you know, we have whatever our day to day routines look like (fully automated luxury communism with robots, or grubbing around for the least radiated roots. Take your pick.) But every Monday we all put on trousers and jackets, tie a strap of coloured fabric around our necks, and gather in cubicled enclosures to worship the Economy for a couple of hours. Apparently it came down to earth once and changed everything about how we live, and now it has to be appeased lest things change too much again.

I found the research paper by Laura Deitrich on the vessels and tools from Gobekli. It has an overview photo of the entire site, with the finds mapped out meticulously in a chart underneath the photo.

There are many photos of the stone vessels, some of which are greenstone. They are made by shaping and hollowing out a large rock. I haven’t read enough to see if they know the source of the various rocks used for making them. River cobbles seems likely, and they clearly had plenty of time to work stone.

The circular monumental spaces are early constructions which notably have very few finds. The smaller structures surrounding the communal circular structures (where most of the vessels and grinding tools were found) were later additions, and were dedicated to processing grains into food and brewing grain based beverages.

There are stone structures nearby for trapping game in quantity. It discusses bone finds and game species in the feasting remains.

I think it’s more akin to a Sacred Moose Lodge, where all the local clans would meet up to drink beer, meet eligible bedpartners, and brag about their exploits at the annual communal hunting event. Each clan has a pillar and a shelved niche.

Link with extensive references and info.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-archaeological-site-of-Goebekli-Tepe-Above-Main-excavation-area-German_fig1_345259720

Ketil Tveiten@#6:

Marcus, you’re in the wrong century here. «It has walls, so it’s got to be a fort» is the 17-1800’s style of archaeological hot take.

More like a defensible house, but the same can be said for “it has big stones, so it’s got to be a temple” idea. Granted, religious/ceremonial spaces do not have to have anything for a particular reason – it can have megaliths if it wants to – (see Stonehenge) but simply declaring it to be the most ancient temple is a bigger stretch than pointing out how the layout of the place facilitates defending it.

Also, the fact that there aren’t signs of fighting in the strata could be a good argument that it worked and was a tough enough-looking nut to crack that it stood for centuries until agriculture was improved and the residents decided to move along.

Even if you don’t want to buy my argument that the place is a fort, the T-megaliths are still very consistent with roof supports. There is an older site I’ve been reading about and, amazingly, the archeologist there have no problem seeing roof supports for sod-covered roofs, more or less like the Gobelki Tepe T-megaliths, except assembled out of smaller rocks. I’ll try to dig up some pictures and stuff from that, in a bit.

bluerizlagirl@#17:

Some things only look bad when you know there is an alternative. I think slavery is more or less inevitable in any human society that has not yet developed the technology to build an engine capable of turning fuel into kinetic energy.

Well, if there is conflict (or even trade…?) there are going to be winners and losers. What do you do with the losers? Nobody in ancient times would build a prisoner of war camp and store survivors. They’d either save the mouths to feed, and just kill them, or put them to work. To me, it doesn’t seem far different from an authoritarian kingship – “come and see the violence inherent in the system!” – there’s a social contract and it says, “obey King Thag. or else.” I’m cynical enough that I don’t see an authoritarian kingship as a big step from servitude, and slavery isn’t a big step from that, either.

I don’t think the good old days were particularly great.

Such a society also would be vulnerable to a hostile takeover by any other, less-egalitarian society that had managed to overcome both the aversion to coerced labour and geographical separation from its neighbours.

Any society that is committed to aggression enough to build a professionalized military is going to tend to steam-roll the egalitarians. I know it’s a right-wing stereotype but totalitarians do militarize well, until their economies collapse under the weight of their military.

Tethys@#14:

A team from Ankara University unearthed more than 100 ornaments buried in the graves of 11 thousand-year-old individuals during excavations carried out in Boncuklu Tarla between 2012 and 2017.

I was reading about Boncuklu Tarla last night, instead of sleeping, and it’s pretty amazing. There is also an even older site called Ohalo II. [wik] It appears that they were doing some pre-agriculture, including having geared up to grind grains. That sent me off down a rabbit hole trying to read all the various archologists’ theories of where the oldest example of bread-making is, etc.

Also, the Archeologists I was listening to, who were talking about Gobekli Tepe described it as “pre-flint” but Ohalo II is 25,000 years old and has flint artifacts including an incredibly beautiful sickle that I think I may have to try to recreate in carbon steel or bronze.

Obviously I’m not the only person who looks at Karahan Tepe and Obekli Tepe’s monoliths, and sees roof supports. To me, the fact that they are aligned to the same plane is a dead giveaway, but maybe that’s because I spent too much time last summer putting support beams under the floor of an old house. To that point, my co-worker, Mark, and I probably didn’t have any tools that were more sophisticated than the builders 15,000 years ago did. Hmm, maybe we did; I used a clear plastic hose filled with water to level the tops of all our supports.

Anyhow, one other thing I need to cop to immediately: I am extremely uncomfortable with the obviously high level of bullshit that there is about these ancient sites. I saw one youtube thing that was asserting that one of the pictures was clearly of a stegasaurus. And there are the alien visitors people, too. It seems to me that the only way to tell if a source is any good is by reviewing a lot of their material and applying a heavy skeptical challenge to basically everything.

So, this one youtuber had a guy who enjoys ancient architecture fiddle around with trying some strategies for using the monoliths at Karahan Tepe as roof supports:

[source]

[source]

What’s interesting about Karahan Tepe is it’s a lot older then Gobekli Tepe (relatively) and it could be a transitional form of construction. For one thing, the Karahan Tepe buildings were partially buried, presumably for warmth(?). They were entered by jumping down a hole in the roof, apparently, onto a sort of stair. Gobekli Tepe seems to me to be an extension and more expensive version of the same concepts, with an additional curtain wall that I believe was defensive, for reasons I have already explained.

The dwellers at Karahan Tepe appear to have buried their dead under the floor, which was apparently a thing in a lot of other hunter/gatherer sites. That doesn’t make the building a ceremonial building, any more than it makes a medieval castle a ceremonial building, it just means that if you’re shifting rocks and materials around and you have a dessicated (past the point of smelling) corpse you want to get rid of, it’s a good place to store grandma.

Bekenstein Bound@#16:

1. The structure may have served different purposes at different times or even at the same time. Especially likely if it saw use, continuously or on-and-off, over thousands of years.

Very good point! It’s extremely hard for me to conceive of a site in use for thousands of years.

It’s also quite possible that the place may have been upgraded at various stages. Perhaps it was an enhanced version of Karahan Tepe, and hundreds of years after it was a successful location, someone ordered a wall to be built around it. To support outbuildings? To break the wind? For defense? To please the gods? Because the aliens’ sophomoric humor made them do it?

Prehistory, I am finding, is very very different from looking at Egyptian or Roman stuff: they tended to write things down and had complete economies and bureaucracies. I guess that many of these things will just be mysteries for a long time.

Another structure that puts an elevated “parapet” or steps around the inside perimeter is … a stadium, or auditorium or similar. The steps/parapets could have been audience seating for performing arts or sports taking place in the center, where they would have a good view. (Any indications or estimates of what the acoustics would have been like, presuming either an open top or a thatch roof?)

I don’t think the places are very big, so the acoustics would have been good enough for someone to yell. Perhaps it was a ceremonial death-match pit. Or a great hall where King Thag could feast his guests with beer and roast goat. Or, sure, a temple. I guess it’s civilization dependent, but I imagine there’s some kind of “heirarchy of needs” for a civilization: first you need a sleeping spot under a roof, then a cooking place, then a temple for Pope Wizzy, or a great hall for King Thag, then storage, etc. I remember I was listening to some fascinating podcast about ancient civilization in China and one of the archeologists offered the view that you can tell it’s a civilization when you see signs of a privileged upper class. Uh, wow. Not sure what I think of that!

Hierarchical societies will want to keep the laboring classes busy 365/7 since idle underprivileged people might spend the time organizing up a revolt otherwise

True. I remember reading something about the people on of the Polynesian islands, who basically lived in a tropical fruit garden year round, in the middle of a fishery, who the British considered remarkably lazy because they didn’t see any need to go forth and imperialize or something.

Once the sledge is moving it would not be very hard to keep it moving (avoiding being run over by it when going downhill would be a bigger challenge, as well as cornering)

The stairs of the Forbidden City in China are a single block of stone that weighs something like 300 tonnes. Solid marble. Moved 60km. By building a road, pouring water on it to form ice, then towing this giant block using oxen and people pulling and pushing from the sides of the road where the ice wasn’t. Uh. Uh. I have trouble wrapping my mind around the idea that people were excited to do that and rushed to volunteer, but it’s true people get up to some crazy things. I was stunned to learn a few years ago that a lot of the pyramid-builders were professionals, not slaves. And there was no shortage of people who wanted a good job working on pyramid schemes.

So, maybe, yeah.

I was also thinking maybe all the carving happened later. Perhaps someone came by and said “hey this rock is harder than that rock, use this!” but I also think it would probably be a really bad idea to be carving on one of those roof supports (or ornamental megaliths) and cause it to crack. Splat.

As for the purpose of the structure? If it wasn’t defensive, did have audience seating, and also had images of scavengers consuming the dead, then maybe … funeral parlour?

When I was a kid, I remember visiting the cathedral at Albi in the south of France (more !@*&%!$* medieval art!) – it was built during the Albigensian crusade, when the catholics were trying to kill off the slightly less catholics, and it was a cathedral, with a crypt for burying important people, and it had archery slits and some impressive walled courtyards. In other words “all of the above.”

mikemcnally@#18:

(many sensible things I won’t respond to because why)

It looks like for a long time, people could just, well, walk away. I think there is good evidence from the Cucuteni-Trypillia sites + other Neolithic-Chalcolithic cultures that mobility was probably higher than it is nowadays.

Yes, that certainly seems to be true, and I suspect it had a lot to do with how humans spread out and occupied the whole planet relatively quickly. If you do not like the rule of King Thag, you just leave. But you’re taking your life in your hands when you do so. Then again, you’re taking your life out of King Thag’s hands and that might be a good trade. I’m reminded of all the European colonists who went west in North America and carved out farms in the wilderness, killing or being killed but mostly being ignored and ignoring everyone that they could.

Of course, it turns out that if you do enforce things like debt, ownership, slavery, serfdom, obligation, and other forms of power, well, your society is very effective at eating up anyone else around you.

You might appreciate Ramp Hollow [stderr] which is about how American homesteaders were turned into taxpaying members of this civilization.

But every Monday we all put on trousers and jackets, tie a strap of coloured fabric around our necks, and gather in cubicled enclosures to worship the Economy for a couple of hours

Ah, that’s what Gobekli Tepe is: it’s an Amazon distribution center.

Boncuklu Tarla:

It seems likely that they had roofs. The outer wall not only restricts human entrance, it could prevent wild animals from entering the space. Hyenas and Jackals are common in the artworks.

It is unfortunate that the word temple has been applied by some researchers and various ancient alien weirdos who make YouTube videos.

The change from semi nomadic to permanent settlements took 1500 years, and the various sites show a gradual evolution in decoration of the pillars, but the basic architecture doesn’t change much.

Perhaps the first structures were used as lookouts for herds of game? There is no evidence of King Thag or social stratification.

These people have everything they need in abundance within a short distance. The seasonal migrations of herds of animals would have been very important for creating food surpluses with just a few weeks of effort.

My previous link details various stone platters and large vessels which were found at Gobekli. One platter is carved to fit on top of a vessel, and has a hole for drainage. It’s the world’s oldest colander. A piece of cloth over the bowl would make it useful for straining beer, or it could be used to collect blood from animal heads to make soup.

They are placed next to a carved stone boar.

They took a great deal of care in placing carved objects before decommissioning the structures.

I believe this area is prone to earthquakes, though none of the literature mentions that. Perhaps they were damaged before they were filled in again?

The earliest fired ceramics were found at Nevali Çori. (Figurines and beads)

The whole article is worth a read. It also discusses Karahantepe, which hasn’t been excavated down to its floor levels in some of the “special structures”.

https://www.archaeology.org/issues/543-2403/features/12122-turkey-neolithic-monumental-structures

There is one architect (not archaeologist) Sarah Ewbank, who is convinced that Stonehenge also had a roof. I gather that her ideas are not widely accepted among qualified experts.

avalus@#10:

“That is the place where our mothers and fathers met with others and errected a stone. They told us in their stories. This year WE will meet with others, WE will errect another stone. And we will tell stories to our children, so in the future other people will come and erect their stone and tell tales.”

You make many good points.

I’m not trying to be flippant but I could just as easily respond, “That is the place where our mothers and fathers fought off the raiders who would have killed or enslaved us when we were children, like in that Conan movie and endless Viking TV shows. We will stand our ground there, and add more stones, that our children can shelter behind, that we can defend, so in the future other people will come and erect their stones, drink that pisswater we call beer, and tell those in Sparta that here, we did not die.”

Reginald Selkirk@#28:

There is one architect (not archaeologist) Sarah Ewbank, who is convinced that Stonehenge also had a roof. I gather that her ideas are not widely accepted among qualified experts.

I’m not a qualified expert by any means but it would be awfully hard to get roof-beams up that high. On the other hand, lots of head-space for smoke would be nice. On the third hand, that’d be a monster huge enclosed space.

I have not studied much about Stonehenge but I seem to remember reading something about that they had found signs of the builders’ encampments, or something like that. I’d suspect that the same roofing techniques would be applied, since they’d know they’d work.

Tethys@#27:

The change from semi nomadic to permanent settlements took 1500 years, and the various sites show a gradual evolution in decoration of the pillars, but the basic architecture doesn’t change much.

I can’t even wrap my brain around 1500 years of incremental improvement in architecture.

Last night, drifting off to sleep, I was wondering if the outer walls around Gobekli Tepe were added after further experience with weather or animal husbandry or human on human warfare or something I haven’t even thought of.

I also imagine that settlements would occasionally just … die. From flu or pox, or whatever. I suppose that as humans began to live closer to animals, zoonotic infections would become more common. I wonder if any tribes said “fuck this!” to agriculture after one of their settlements died off from some sickness.

The architecture of Boncuklu Tarla, with everyone down inside in a hole, just seems like a great way to get slaughtered. It’s actually the inverse of defensible: it’s a death-trap. Perhaps realizing that was another incremental improvement in architecture.

There is no evidence of King Thag or social stratification.

These people have everything they need in abundance within a short distance. The seasonal migrations of herds of animals would have been very important for creating food surpluses with just a few weeks of effort.

True. As I mentioned, that podcast about ancient China claimed that civilization could be demarcated by the rise of a class hierarchy. I want to walk a fine line between accepting the ideal of the “noble savage” and the “dark forest” view that King Thag will eventually appear when there is surplus that can be taken through intimidation. I always see King Thag as a vicious lazy thug.

My previous link details various stone platters and large vessels which were found at Gobekli. One platter is carved to fit on top of a vessel, and has a hole for drainage. It’s the world’s oldest colander. A piece of cloth over the bowl would make it useful for straining beer, or it could be used to collect blood from animal heads to make soup.

I saw some great episode of some show, where they made ancient-style beer. It sounds horrible. But it’s water that you can drink without getting dysentery. [That’s a subtle thing the ancients seemed to catch on to, but the British in the Crimean war were defecating into the same river that units downstream were washing in and drinking from. Which is why Colin Campbell put his highlanders as far up-river as he could, so all the British downstream would be drinking ‘highland tea’]

Anyhow, it seems that argues less in favor of a temple than a feasting-hall. I could easily see a tribe of hunter-gatherers who had their winter quarters in a nice walled place where they could hole up, drink beer, and eat jerky.

I believe this area is prone to earthquakes, though none of the literature mentions that. Perhaps they were damaged before they were filled in again?

That isn’t mentioned much, though there was some mention of a landslide covering parts of the structures, plus human efforts to cover parts.

It’s fascinating. Maybe there was an earthquake and they decided that the gods didn’t like that spot so much. Though, I have to imagine it would take something impressive to make people abandon 1,500 years of work. Usually, I remind myself that most human disasters are caused by other humans. But that’s the modern world.

1500 years means the people who built it and those who buried it were different people, separated by many generations. To the buriers, the site might have been a symbol of a discredited, archaic social system they had no further use for; and that’s assuming they were even the descendants of the builders, rather than invaders who had succeeded in taking over, for whom the site might have been a symbol of a hated enemy.

As for “noble savage” vs. “dark forest”, I second an earlier recommendation made by another poster to read at least the first chapter or two of that Dawn of Everything book.

I’ll also note that in a pre-existing, egalitarian society some selfish jerk declaring himself “king” and demanding tribute would simply be laughed at, and if he tried to back this up with a credible threat of force he’d be tarred and feathered at best and quite possibly just killed.

It actually takes a lot of social infrastructure to get, and maintain, that sort of stratification. Thag needs a cadre of loyal guards, or at least a goon squad like Biff Tannen’s trio of dickheads, backing him up, at a bare minimum. In practice it would be very hard to get from living like bonobos, or something similar, to having a king, without a long period of normalizing gradually worsening inequality in between and the gradual accumulation of strata and associated social infrastructure, from norms to police forces to giving pretty much all people outside the bottom-most stratum enough of a stake in the system to generally support it rather than join with the bottom stratum in desiring its overthrow. I doubt a stratified society could spring up overnight.

Also, both storage and civilization are prerequisites for a stratified society. As noted above, stratification requires at least some social infrastructure, including norms inculcated throughout the populace, implying some type of educational system, though not necessarily one with dedicated school structures or a specialized teacher profession. It also requires there be surpluses for the upper strata to steal, which seems to require storage. I’d say that storage and public infrastructure (the latter being my determinant of “civilization-or-not”) must come first (storage goes hand in hand with transport infrastructure anyway), and stratification can (but perhaps not must) develop after that, when there is a surplus to distribute inequitably in the storage and there is a large enough investment in the storage and infrastructure, “roots put down”, to make “cost of switching” high so everyone doesn’t just say “fuck that shit” and go join the Iroquois, or the Babylonians, or whoever the local alternatives might be.

Put another way, stratification’s onset is something like what Cory Doctorow calls “enshittification”. First you need a civilization that’s worthwhile living in. Then you need to take over control of it … somehow. Then when everyone is sufficiently locked-in that there’s a high cost of switching, only then can you start to divert more and more of the surplus to yourself and leave less and less for the people at large without fomenting a revolt that, at best, leaves you sitting there alone and a laughingstock and at worst sees you swinging on the end of a rope.

So, it wouldn’t happen overnight, and it would happen most readily in a place that was sufficiently crowded that there weren’t really any good alternatives nearby accepting immigrants either.

Further: nobody would even think up such a scheme in the first place until the concept of “ownership of property” itself was invented. That probably happened among the nomadic herders of the Great Asian Steppe, who developed clan-level ownership of herd animals. Then raided and warred (escalating from cattle rustling to, eventually, genocide) and then discovered that due to Lanchester’s Square Law and the nature of the steppe terrain, plus everyone being at technological (and thus firepower) parity, victory depended almost entirely on numerical superiority, with even a small numerical advantage quickly becoming a very big probability of winning, and even a moderate one sufficing to ensure you took only light casualties in doing so.

In the short term, for one battle, that would suggest arming every able-bodied adult and sending them to the front lines; but in the long term, the clans that would be most successful would a) ally with other clans and b) maximize population growth, and the rate of rebound from losses as well. That meant you got huge alliances and it also meant subjugating women to the role of being baby factories. The steppe environment and the nomadic herding lifestyle also have almost no limits on polity scaling, so these alliances eventually came to be the size of the steppe itself, with Genghis Khan’s hordes. Long before then, these had inflicted misogynistic norms on themselves and everyone they subjugated.

I suspect that the origin of a social hierarchy as well as a gender hierarchy lies with these guys, and the origin of stratified societies and King Thag is with horticulturalists near the steppe who were subjected to raids of their surpluses, not by uppity members of their own society, but by their warlike sometimes-neighbors. The raiding could easily evolve into a protection racket: leave enough for them to take at a regular time of the year and they won’t kill people and set all your buildings on fire. The protection racket can then evolve from absentee landlords to not-absentee landlords, where descendants of the raiders settle permanently nearby, if the tribute is enough to live on without the nomadic herding any more, and to escape the population pressure and periodic Malthusian crashes the maximize-birthrate ethos would now be causing on the steppe.

Once the landlords are live-in, you have: a ruling class that is hereditary and demands tribute; animal husbandry, including horses, and a cavalry consisting of men drawn from the ruling bloodlines; and a peasant laboring class. Sounds a lot like King Thag’s proto-feudal society. They would also have brought their misogyny and their “big sky god” religions, e.g. Tengrism, replacing the sort of animism and ancestor-worship more typical of paleolithic-lifestyle cultures. And of course the idea of ownership of property also arrived with them. So did militarism as we generally conceive it now, with much of the male population trained for war and on standby to be called up for service. With their experience in war, archery skills, and war-horses and other animal servants, the herders would have easily, as you said, steamrolled any opposition, making the protection racket by far the easier option than trying to fight back for anyone not in a very defensible position.

If Gobekli Tepe was a fort, it was likely to defend against Great Steppe raiders attacking from the north. They wouldn’t have had horses yet at 12,000 years ago, but they were probably still in sizable hordes with an advantage in military skill and equipment over contemporary peaceful horticulturalists and hunter-gatherers. The latter, at least, might have been able to just avoid being there at times of year when the raiders tended to come, but they’d reliably come at the former’s harvest-times once they learned what those were.

that image @22 needs a scale

whatever it is, it was never used

“Remember what I mentioned earlier about the theory that storage led to agriculture?”

Have you read Dark Emu? There’s some discussion in it of groups here who weren’t permanently settled but still farmed areas and built storage buildings. They would move to the area when they needed to do stuff (harvest and plant i guess?) and then travel elsewhere for the rest of the year for other activities

There was an account by a European who found the buildings when people were away and raided them for stored grain

There is very little evidence of social stratification or social conflict in the archaeological record until the Bronze Age.

Metals and the control of mines develop in tandem with weaponry and large scale warfare.

Keeping your food caches safe from wildlife would be a priority if you aren’t there to protect them, but there really aren’t any large populations of people or cultures to have conflict with 13,000 years ago.

As for roofs, I find it amusing that the people who did reconstructions created standard, squared lumber beams, with fancy angles. Ummm, no. Miter saws and nails aren’t a thing, though stone axes were common.

It is possible that the three structures at the top of that vulture pillar are depictions of the other three (older) structures. The roof is domed, and each has a ‘totem’ animal next to it, just as each enclosure has a dominant animal depicted on its pillars.

These people not only buried their family under their houses, but they also had a custom of digging some of them up later and removing the skulls for further usage.

This link is the actual dig diaries of the archeologists. They are German, so sometimes they write very confusing sentences in English, but they are very trustworthy sources. This is just one page of information on the subject of heads.

https://www.dainst.blog/the-tepe-telegrams/2016/05/05/losing-your-head-at-gobekli-tepe/

Here is another page that details another slab that’s carved with a vulture and a head.

https://www.dainst.blog/the-tepe-telegrams/2017/05/17/a-separated-head-between-animals-on-a-stone-slab-from-goebekli-tepe/

Compare the head carving style of the similar aged ‘Venus’ from France. Nice photos of a beautifully carved reindeer spear thrower and various other Paleolithic artifacts included.

https://kids.kiddle.co/Image:Venus_de_Brassempouy.jpg

chigau@#33:

that image @22 needs a scale

whatever it is, it was never used

There was a scale in another image; I am going to assume it’s the same … ?

Which makes the overall length about 8cm. Which is fairly small in terms of what we’d now think of as a “sickle” but having tried to break grass by hand I can imagine it’d still be valuable.

anat@#15:

Marcus (and anyone else who might be interested), please read ‘The Dawn of Everything’ by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Thank you for that. I am halfway through it and my mind is seething with ideas. I’m going to have to elaborate eventually but I’m still sanity checking myself.

I’m not expecting you’d mind but I think I’ll write a review of it and add it to my recommended reading list.