If you ever find yourself believing that America is or was ever great, you can cure it with a dose of Howard Zinn. It won’t take much, but sometimes it aches going down. If you don’t have any Zinn handy, you can substitute Chomsky.

Other than his landmark A People’s History of The United States [recommended!] Zinn wrote and spoke a great deal of thought-provoking, interesting, and sensible stuff. Unfortunately, some of it has gotten hard to find – in the pre-youtube days not every great speech wound up being recorded for posterity and shitweaseling.

Apply to forehead

KPFA’s podcast, which I subscribe to, recently had some lengthy extracts from a speech by Zinn entitled: “The Southern Influence on National Politics” [kpfa] As always, Zinn is devastating:

I’ll tell you why I don’t like to talk about southern influence in national politics. Because it perpetuates a kind of mythology which I think is very prevalent in American thinking, and probably in foreign thinking about The United States, and that is that we have here a fine, decent, democratic, beautifully structured, lovely country which the south is spoiling. We have some great statesmen in this country, we have a good congress, we have a fine president, a magnificent supreme court, a wonderful set of laws, a great constitution, a magnificent heritage and all is being spoiled by a few miserable, evil southerners.

I don’t think this is true. And you know this isn’t true.

The thing that’s wrong with that myth is this: that racism is not a southern characteristic, it’s a national characteristic. Racism is not a southern problem, it’s a national problem. And this has been a very easy way for us to dispose of the whole situation – we’ve done it all the time. This nation, historically – we very often forget – has been, for most of its existence, a slave nation. I’m counting its existence from the 17th century, as a social entity, and we have been slave longer than we have been free. And, if you count our existence from the declaration of independence, the years that we have been a slave nation and the years that we have been a free nation are pretty close to equal. It’s not a matter of north or south – and we find this out when we go north and negroes move north; the negroes leave the south and they go up north and they get to New York City and they get on an express train that doesn’t stop ’till it gets to Harlem.

I want to say a few things about the Kennedy administration, only because it happens to be in power now, and only because it is a natural example for the whole problem of “is this a southern crime, or is this a national crime?” We have too long treated what we have done with the negro in this country as a kind of aberration on the part of what is otherwise a normal, healthy, American society. This is completely false. It’s as if you knew somebody who was a very nice, sweet, person – most of the time – but just one day a week he went out and found someone and killed him and ate him. Then, if you had to write a letter of recommendation for this person, you’d say, “well this person is very dependable, reliable, conscientious … he has one little fault, which we’re trying to correct.”

I’ve clipped the bit above into an audio file, if you want to hear the original. I don’t think I should post the whole audio (and KPFA don’t provide a complete version, anyway) Zinn’s delivery is interesting: tired-sounding, sharp, and he drawls “southern” like a proper kid that grew up in Brooklyn.

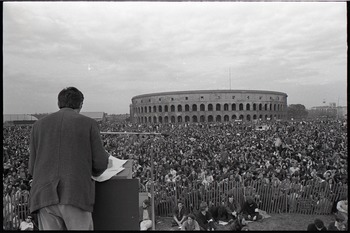

Howard Zinn at a peace rally at Harvard, 1970

From there, he takes the Kennedy administration, which is currently portrayed as “progressive” and “liberal” (in spite of its brutal war in Vietnam) to task:

The Kennedy administration has played this myth of southern conspiracy/southern evil to the hilt. And it’s easy for them to play it because there’s a basis of truth to it. The worst racism is in the south, the worst acts of violence are in the south, the worst senators come from the south – in fact, I could go further and say they come from Georgia – but there are people here from Mississippi and we’d have to argue about that. There’s reason for saying this about the south, and the rationale of the national administration – when you begin to talk about national responsibility for civil rights, you take a look at the committee structure in congress. And I will now take a look at the committee structure of congress…

Here is the list of senate committees for the 88th congress – take a look at the chairmanship of the committees:

- Agriculture and Forestry: Ellender, Louisiana. Well, maybe that’s where he belongs, this is good.

- Appropriations: a very important committee in the senate, well this was given to somebody in Arizona, by some mistake.

- Armed Services: Richard Russell of Georgia.

- Banking and Currency: Willis Robertson of Virginia.

- Finance: Harry Byrd of Virginia.

- Government Operations: John McLellan of Arkansas.

- The Judiciary Committee of the Senate – and I must now read the official designation of what the Judiciary Committee is supposed to do – it has jurisdiction over federal courts and judges, civil rights and civil liberties, constitutional amendments – Chairman is James O. Eastland of Mississippi.

- Labor and Public Welfare: Lester Hill of Alabama.

- Post Office and Civil Service: Olin Johnson of South Carolina.

- Rules and Administration: Everett Jordan of North Carolina.

More than half of the standing committees of the senate are chaired by southerners.

The administration says, as every administration has said, “well, you see, this is a problem we face – it is built into the situation.” But that’s not quite so. Because, outside of this framework – above and beyond it and over it, the administration has had an opportunity to do things, if it wanted to which could have nullified this power set-up, changed it, and in some ways created a possibility for decent civil rights legislation in congress.

When Kennedy was elected, if you can remember – there was some expectation, some hope – in the field of civil rights. And I was expectant, like everybody else. He had not yet taken office, he was elected but not yet inaugurated, but congress had convened and Kennedy men were already in power in congress: Mansfield, the majority leader and others. The Kennedy machine – that great machine which had succeeded in winning the election for Kennedy by magnificent manipulative process was now operating in the senate and there was real hope. So, the senate opened and the very first thing that happened was there was a battle on Rule 22 – a very important rule for civil rights. Because Rule 22 decides when you can shut off a southern filibuster. It says you can only shut it off when you have 2/3 of the senate voting to shut off debate. Liberals have been trying to get rid of Rule 22 for a long time so they can stop a southern filibuster so they can get civil rights legislation through congress, particularly thorough the senate, which is a big stumbling-block and the scene of so many filibusters.

So, the first battle comes with the opening of the senate right after Kennedy is elected and a vote is taken on amendment of Rule 22 to make it easier to stop filibusters and the vote is 50 to 46. Two votes made the difference. If two votes had switched there, we would have had a tie vote and Nixon, it’s clear – with all the things we say – would have voted to change the rule. Kennedy, – and everybody who observed the political scene at the time, and since agrees pretty well on this – could have switched those two votes, and didn’t.

What Zinn has just identified is the real process behind the US government. It’s not just a vote-trading back-scratching self-licking ice cream cone: it’s a representative process that is gerrymandered internally. It’s structured so that it cannot really be changed to disempower the southern political bloc; this is the same trick that the south played over and over again on the people of color that live within its borders.

When I listened to Zinn’s account, I think I know how Rousseau felt, when he discovered that Zurich was actually run by a political system that was hidden behind the pseudo-republican system that everyone thought they were dealing with. Zinn goes on to describe how the senate steering committee, which determines the legislative agenda of the senate, was entirely controlled by southerners.

How’s that “representative democracy” working for you?

The complete speech is available from the Pacifica Radio Network, or from KPFA as a donation gift. I’ve ordered a copy of the archive but I don’t know how long it’ll take to get it. Naturally, I won’t be able to post it all, though I’m pretty sure I’ll be posting extracts.

“… we have here a fine, decent, democratic, beautifully structured, lovely country ” and all I could think was “it’s the best country ever, it’s yuge! great people!”

“… we have here a fine, decent, democratic, beautifully structured, lovely country ” and all I could think was “it’s the best country ever, it’s yuge! great people!”

Good sarcasm does not come with an expiry date.

Those of us who study British history are aware that the reason for the Slaveholders Treason in 1776 had little to do with liberty and rather more to do with what is known as the Mansfield Decision

( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somerset_v_Stewart )

which effectively outlawed slavery in Britain and was seen as the writing on the wall for Colonial slavery so yes we know the US was built on slavery.

AndrewD@#2:

Those of us who study British history are aware that the reason for the Slaveholders Treason in 1776 had little to do with liberty and rather more to do with what is known as the Mansfield Decision

Yes, my take on Somerset V. Stewart is here [stderr]

I agree with your analysis: the US secession was about the exact opposite of “freedoms”!

and yet, the virtuous Brits went on to build a brutal continent-striding empire that among other things starved the Indians, set up Apartheid, etc. etc. etc.

Let’s not be too self congratulatory here.

And today bmiller which nation comes closest to being a fucking shithole?

The last country on Earth I’d visit is the USA. I’d rather live in fucking Saudi Arabia.

I wonder if the importance of the Mansfield/Somerset decision has been exaggerated. Sure, it was unwelcome in slaveholding colonies, but it took Britain another 60 years to end slavery in its colonies, so it’s hardly like there was an irresistible push toward emancipation by the time of the American Revolution. It also doesn’t explain the push for separation from Britain in colonies that would end slavery on their own shortly after independence. As is usually the case in history, the causes for US independence were many and complicated.

As for whether the USA is admirable or detestable, I guess that depends on who you ask. For my own part, I feel that this country and society have been good to my ancestors, myself, and most of my friends and relatives, so I certainly feel some affection and gratitude. I also think that those who condemn the USA can be somewhat myopic, in the sense that most of the faults of the USA are found in nations and societies around the world which get a free pass for those faults because, well, they aren’t the USA.

Nogbert@#5:

I’d rather live in fucking Saudi Arabia.

I’ve been to both the US and Saudi Arabia and I don’t really ever want to go to Saudi Arabia again.

springa73@#6:

I wonder if the importance of the Mansfield/Somerset decision has been exaggerated.

Historians spill a lot of ink over questions like that – the problem is to try to identify what causes were really important to what effects. It’s hard.

There wasn’t a push toward emancipation, at the time of the decision, but on the reverse of that coin, the American Colonies founders (the political agitators) kept talking about only 3 issues: billetting troops, taxes, and “taking away freedoms” – The Crown had actually been offering to expand political freedoms in the colonies at that time (they offered seats in Parliament and the colonies weren’t interested) so, what freedoms were being taken away? Perhaps in a general sense, “the freedom to do whatever we want” which also overlapped into smuggling and making liquor and luxury goods in a relatively unregulated environment, but it’s impossible if you look at those economic issues to separate them from slavery, which drove Tobacco, Cotton, and Rum (sugar!) production. Perhaps the colonists were concerned that slaves, as valuable property, might become subject to taxation – but that just gets us back to the main issue.

As I said elsewhere, [stderr] there are historians that argue “it was all about slavery” and there are others who say “it’s more complicated.” Personally, I side with the “it’s more complicated” view but I still place slavery and the threat of regulation of slavery as front-and-near-center in the problem. I’d say front-and-center was smuggling, but smuggling, slavery, and taxation were interdependent issues.