My day began with a bit of panic. Where are my car keys?

I loaded up and was ready to go and I couldn’t find the keys. There’s a security key-fob system that lets the car know the keys are nearby so I can tell by process of reverse elimination that the keys aren’t on me, not in a pocket, not in my briefcase (which is in the trunk) or my camera bag. After too much scurrying about I deduce that I must have left them when I was fixing my coffee, and walk cooly back, pick them up, and depart.

There’s always a bit of “get to know you” to do, first, which I enjoy. Especially because Samson, a big black shaggy shepherd-dog puppy (about 100lb) takes a liking to me, and presses up against me while insisting that his head is badly in need of rubbing. I take a liking to him.

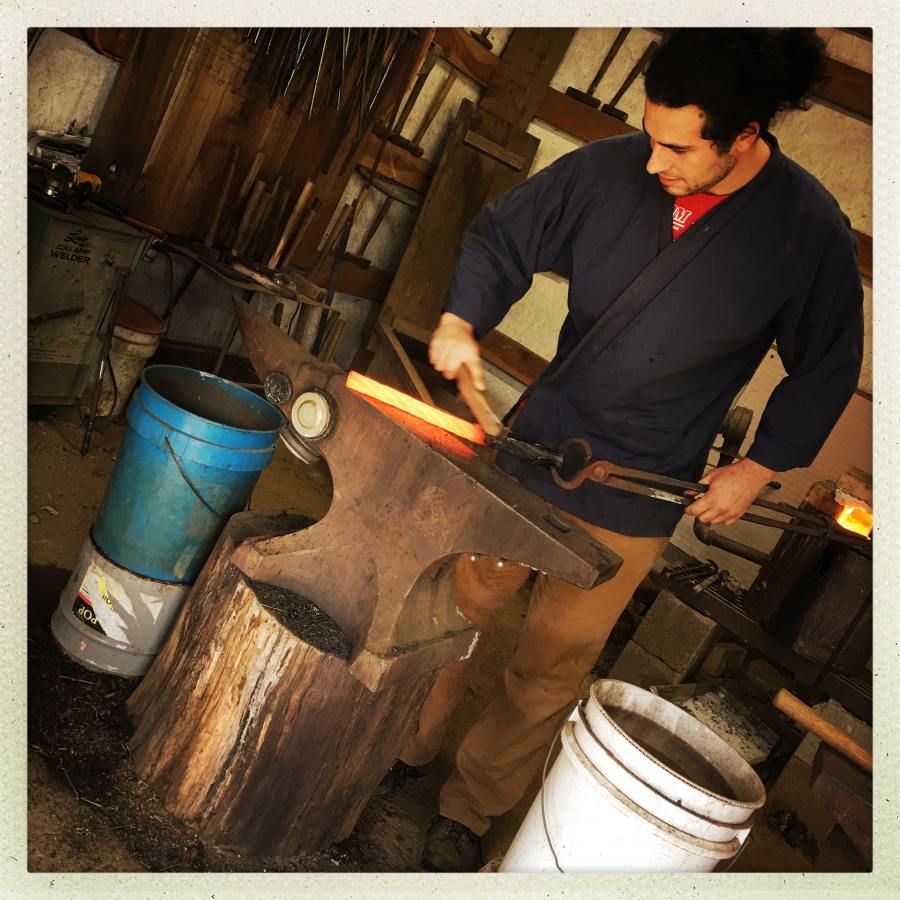

There are a few outbuildings; an office/polishing area and the forging area, where “dirty work” is separated from the clean work. Blades of various types and in various states of completion are all over the place.

I was surprised (and very pleased) that the work is not extremely kinetic. There is a lot of “wait for metal to heat” then hammer on it, think (as it cools) where it needs to be hammered on next, and put it back in the forge to heat again. You get a few whacks in and the thermal mass of the anvil starts to suck the heat out of the steel. It’s easy to see where the contact-points are between steel, anvil, and hammer – they cool faster.

We’re making short sword-blades (something between a small wakizashi and a long tanto) out of welded cable. The cable-welding set-up is done by Gabriel Bell, while we watch and observe the technique.

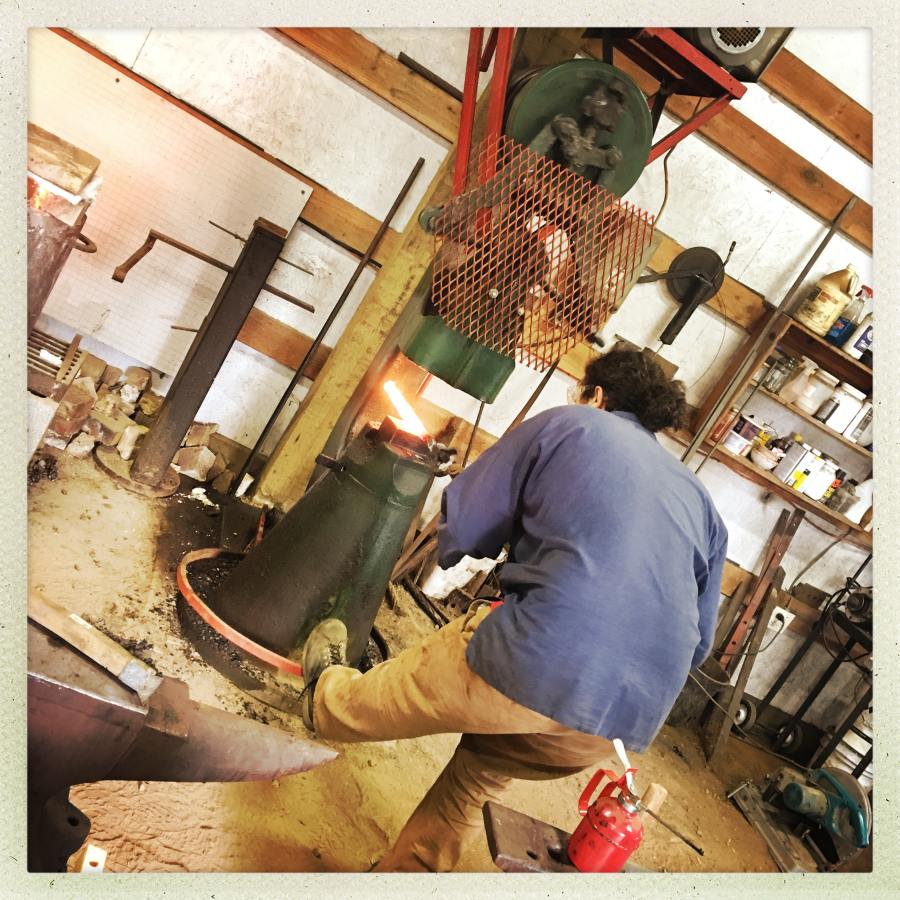

To start, Gabriel chopsaws off about 17″ of steel drag-line cable; it’s the same stuff that’s all over Pennsylvania from running strip-mine drags – out in Oregon they use it for moving trees. The cable is made of groups of wire that are twisted, and then those groups are twisted into larger groups. I didn’t count the groupings or number of individual wires but I’ll try to do that tomorrow.

The cable is cut, brought to close to welding temperature, and “soaked” in the forge for a while to burn off any oil, zinc, or whatever else might be stuck in there that’s not steel. Gabriel brushes it down with a steel brush, and keeps dumping borax (flux) onto it to melt and fill the spaces between the wires. When it’s brought up to temperature the flux will replace air, then squish out of the way, allowing a nice clean weld. At this stage the cable is still recognizably cable, though it becomes flexible and soft – about the consistency of thick taffy.

A first step toward welding is made by taking the near-welding temperature cable, clamping one end in a vise, and twisting it tighter with a big pair of pliers.

Once it’s all cleaned, fluxed, and tightened, it’s taken over to the trip-hammer and mashed. That’s not the technical term for it, but it fits.

That’s also a contemplative process. The cable gets mashed flat a couple times, turned 90 degrees and mashed a couple times, turned at an angle (to tighten it as it gets mashed) a couple times, then goes back into the heat. I think the process of turning the cable into a welded bar took about an hour and a half or thereabout.

The trip-hammer is an awesome beast; we students don’t use it. Not because it’s particularly dangerous, but apparently it can be damaged pretty easily if someone pulls the metal out before the hammer hits (so it’s hammering itself) – the bar that’s being welded acts as a cushion. It’s pretty cool; you can feel the whole floor pulse when the hammer drops.

Smiths are pretty big on making their own tools; the forges we’re using are hot water heater tanks that have been cut and fitted with a propane/oxygen mixer and lined with refractory cement. The bigger machines like the trip-hammer are precious industrial-age sandcastings; nowadays most blade makers are using hydraulic presses that provide pretty much the same distortion on the metal but without impact.

When the cable has been trip-hammered into a bar about 19″ long, 1″ x 3/4″, everything gets turned off and shut down and we break for lunch.

The next step is cutting the bar in half and each of us gets a piece to work with. Now, I’m not taking pictures because my hands are busy, though I have the 5D on a tripod controlled by my laptop, shooting 20 second time-lapses for most of the afternoon.

Then comes frustration!

It’s a motor skill that simply has to be acquired; figuring out exactly the right angle to tap and where, to squish the metal a little bit. You also have to hold the metal right in your tongs so it doesn’t leave, and you have about 4 seconds to figure out where you’re going to work it next while you’re lining it up on the anvil, then 10 seconds to drop 6 or 7 good whacks in the right place(s), and it goes back into the heat. When you start to bring the bar into a more blade-shaped wedge, that thins the edge, which puts lengthwise pressure on the bar, so it curves. It feels frustrating because you can lay down a good line of whacks and the blade suddenly looks a whole lot worse until you straighten it (after re-heating) and notice it’s gotten a tiny bit longer and wider and thinner. The changes are slight, and take time, so it’s clearly a matter of learning how to estimate your effect. It doesn’t help that the steel looks very different when it’s red hot than when it’s just very hot; you can see the line of the edge that you’re hammering in much better after it’s too cool to hammer it any more.

After a couple hours of whacking, it starts to look more like a sword. That’s a relief.

The teaching process is interesting (I don’t think it’s possible to do it any better) Michael or Gabriel will tell you, “Alright, now you need to hit it here, to push the metal this way, which will make that piece there move a bit that way.” There’s a lot of pointing and waving at red-hot metal, but you can’t exactly handle the stuff, so it’s all from a distance, with a lot of pointing and demonstrating. It’s nowhere near as kinetic as I expected; the pace is slow and thoughtful. Obviously, it’s necessary for there to be four of us working in the same space, so we had to communicate and watch what everyone else was doing with red hot metal. I concluded pretty quickly that, once you know what you’re doing, working alone is probably much safer.

I can see how, once you have a vague idea what you’re doing, it’s much more efficient to hammer-forge your blade into shape than it is to make a bar and grind the blade out of it. Historically, that would also make no sense at all – steel was valuable stuff that was hard to smelt and purify – one would not take a bar of fine steel and grind half of it to dust. Well, I would. But I’m trying to learn otherwise. I enjoy Michael’s explanations of how techniques evolved, historically to the present; I am just gobbling up the information. For example, I learned that early iron (‘bog iron’ and otherwise) wasn’t even as good as bronze, but tin became a strategic resource and iron came into use as an alternative, until the discovery that using charcoal instead of coal produced a high carbon steel that could be quenched to be much, much harder than bronze – and that was the end of the bronze age. As all these explanations flow over me, I keep boggling my mind at the unimaginable amount of trial and error that resulted in the first reasonable-quality steel swords. We also discussed the question of “how did someone figure the clever idea of smelting down iron-sand into iron?” (Answer: probably in the process of making glazes for pottery) This is an art form that has evolved in a great many tiny steps; it was not intelligently designed.

By around 4:30, with a great deal of help, we had managed to shape sword-shaped things out of the metal; the rough shaping is done. Tomorrow, we’re going to switch to using lighter hammers and making more precise shapings.

Coming down out of the creative clouds, I learned about the shooting in Las Vegas. We can ban the damn things; there are laws (in some states) regulating swords and knives – the only difference is that there is no knife-lobby. Otherwise, what about “bear arms” doesn’t apply to a lovely court-sword? In July last year, after another mass shooting, I proposed a straightforward public policy that would transition the US gracefully from a firearmed population into a civilized one [stderr] – I still think my proposal is better and more sensible than the vast majority of alternatives I’ve heard. None of this stuff is going to go anywhere as long as we’ve still got the NRA. So: will someone please shoot those motherfuckers?

See, I — and most people in the civilised world — would have described the trip-hammered bar as “480 * 25 * 20 mm.” Or even omitted the units altogether if I was talking to another engineer because, convention.

How do you actually manage to do any engineering work in those clunky mediaeval units, with fractions — not even simple decimal fractions, but ratiometric ones — getting in the way all the time?

Fascinating! I hope you can find time to continue to write about this.

I learned to cold forge when I was first learning to be a jeweler. I always was captivated by hot forging, there just was no one to teach it where I lived. Doubt I’ll take it up, ever, but still an amazing process.

Oh, what a grand time! I’m really glad this is much more conducive and kind to your joints than you anticipated. I’m with you – get rid of the guns, bring back the sharp and pointy. At least if swords made a comeback, people would have to learn something, fencing! I’m a huge proponent of fencing, I love it, and you have to be able to think to fence well, so that would rule a lot of people out.

V. nice, but let’s have a nice pic of Samson, ‘kay?

Caine@#3:

The problem with sword-wearing and duelling is that it implicitly favors those who have time to develop and maintain the skills. Guns are more democratic (in principle) but they also become a wealth signal in an unequal society. The rich and powerful always game the system (it’s why they want to be rich and powerful) even though Voltaire was fully within social norms of the time when he challenged the chevalier de rohan to a duel, the chevalier simply had him banished to England. Age is also a problem of equality: no 60-year-old roué wants to fence a 25-year-old genius! So I think we need to expand the panoply to: swords, pistols, math, rhetoric, and mario kart. Whoever is challenged chooses their weapon and the loser’s life is forfeit.

Pierce R Butler@#4:

Good suggestion!

Seconding Pierce. Blacksmithing’s all well and good, but don’t bogart the puppy, man!

Looks like you are having a great time! I’m also looking forward to see the final result once it’s finished.

The problem with sword-wearing and duelling is that it implicitly favors those who have time to develop and maintain the skills.

It favors those who happened to be born with the right body. Having free time and determination to train really hard isn’t enough to become a top level athlete. Physically weak people, those with illnesses/disabilities, children, elderly and so on are automatically disqualified. A society where “might makes right” is not fair or pleasant to live in. I love fencing as a sport, but I wouldn’t like to live in a society where it is used to settle disputes. Same is true for guns, fists, knives etc. And in fights luck is important too. My Krav Maga trainer always reminded us to just surrender our wallets and do everything possible to avoid a real fight. To further prove his point he told us about a guy he knew who was extremely skilled in martial arts, but ended up killed in a fist fight because he just got unlucky that day. And I can’t even support rhetoric as a means for settling disputes (somebody who is a great orator can potentially get away with abusing somebody who is shy and bad at oratory). I’d say a society with fair laws (which are the same for everybody) where each person has to adhere to them seems like a better option.

Guns are more democratic (in principle)

Swords favor those with the right bodies and free time to practice. Guns (tanks, drones, battleships) favor those with money. Neither is more democratic.

There’s more to sharp and pointy than swords and fencing. Knife throwing is a skill easily learned and practiced by all. At any rate, I’m not being terribly serious, in case people couldn’t tell.

Marcus,

As a certified Crane inspector, there is a big difference between cable, and wire rope.

Those chunks of dragline are wire rope, not cable. Cable is simply round wires twisted to form a multi wire cable to withstand an extreme force in a single direction: lengthwise. It does have the ability to absorb vibration and low stretch in a single direction lengthwise, but cannot survive bending, without failing. The Guy wires that keep electric poles upright, cellphone towers upright, and fences nice and tight are cables.

Wire rope is made of flat wires, pre-bent into a specific shape, then assembled into a rope. This wire rope can bend 360 degrees, and all the wires slide and move so that during the bend, the length changes are compensated for overall, and the linear force is equalized through the bend over sheaves and drums.

The Metallurgy of this wire is far superior to the metal in cables, and thus is much more desirable for a good, flexible blade, that will take shocks, and not crack, or break. Yet still tough enough to take a fine edge, and keep that edge without much distortion, when most violently impacted.

I’ve been through years of certification on wire rope, and the misnomer of calling rope ‘cable’, is still a matter of difficulty within crane inspectors. Precision communication is just not practiced outside a very few vocations.

So, enough with the education!

I’m a blade freak, and I would love to be there with you making Knives!

Wow, such a pretty place on earth to make them.

I know that you are having a lot of fun, along with quite a bit of “THIS IS MY FIRST TIME, HOW DO I KNOW?”

Just pay attention to your inner self, you’ve explored a lot of art forms successfully, you’ll get this one, too.

I can’t wait to see what you make there.

Happy Forging!

dakotagreasemonkey@#10:

Wire rope is made of flat wires, pre-bent into a specific shape, then assembled into a rope. This wire rope can bend 360 degrees, and all the wires slide and move so that during the bend, the length changes are compensated for overall, and the linear force is equalized through the bend over sheaves and drums.

Aha! Yes, that makes sense. I don’t know the terminology but the stuff we’re working with has been (apparently) polished, worn, or pulled through a die(?) because it’s been burnished so that the contact surfaces are really hard and shiny. It’s beautiful stuff. It’s also ridiculously heavy and greasy and it’s pretty much unbendable by hand. When it’s yellow-hot it gets a bit floppy and makes a thunking sound like you’re whacking heavy caramel.

I’ll see if I can snatch a picture of some of the blades Michael Bell has in his office; they’re also forged from cable and they are full of beautiful transitions between the different wires.

Precision communication is just not practiced outside a very few vocations.

I’ll be careful to get the terminology right; I’m not sure if I’m going to try to correct the Bells, though… “Cable damascus” has become a term of art in the blade-making community.

I know that you are having a lot of fun, along with quite a bit of “THIS IS MY FIRST TIME, HOW DO I KNOW?”

Yep. That’s the joy of learning – the moment when WTF melts into AAH.

I’m a blade freak, and I would love to be there with you making Knives!

Wow, such a pretty place on earth to make them.

And there is great coffee, nice people, good food, and friendly dogs. If you’re a blade freak, this is paradise.

Caine@#9:

There’s more to sharp and pointy than swords and fencing. Knife throwing is a skill easily learned and practiced by all. At any rate, I’m not being terribly serious, in case people couldn’t tell.

Knife throwing is fun! I’ve broken a couple switchblades that way, darn it. (Now, if you can quick open a balisong and complete the motion with a throw, like I can maybe still do but could do well in college, then you can produce some quite surprising holes in things)

I don’t think any of us are being especially serious here on this topic.

bluerizlagirl@#1:

See, I — and most people in the civilised world — would have described the trip-hammered bar as “480 * 25 * 20 mm.” Or even omitted the units altogether if I was talking to another engineer because, convention.

Well, I learned a lot of buildy stuff from my grandfather and my dad, who were usually communicating in inches and feet. I also can approximate metric quite fluently but don’t bother because I pretty much fudge everything anyhow. Grandpa hated to measure anything; he had a bunch of clever hacks involving tricks for folding pieces of string that allowed him to do pretty much anything he ever needed to do (the tricks you learn to do with a compass in Euclidean geometry) so most of the spatial reasoning I do is a mixture of measures and fudge.

I remember when I asked my grandfather why he didn’t measure stuff, and he invited me to get down the steel tape and check his work. It was accurate to sub-millimeter, which is “good enough” for most woodworking.

How do you actually manage to do any engineering work in those clunky mediaeval units, with fractions — not even simple decimal fractions, but ratiometric ones — getting in the way all the time?

I don’t actually think about it at all; it’s usually division by two or subtracting something divided in half from something divided in half, to get a centering measurement. Since I almost always work alone, I don’t even communicate with myself let alone anyone else.

So far, I have seen nothing measured at all in this class. That makes me happy (although I can convert shaku, the Japanese sword-length measure, to feet pretty well. Because. by coincidence, 1 shaku = 10/33 meters – a bit less than a foot.)

It’s like asking someone who’s bilingual in French and English “how can you possibly talk to someone?” Well, the answer is you use whichever one works best in the situation; so I use metric when I want and imperial when I want or pieces of folded string (pifometrics) when appropriate.

The “pifometre” (pif = southern French for “nose”) was a term my dad’s French carpenter friend, Monsieur Foulquier, used because he prefered to measure by nose than eyeball.

Ieva Skrebele@#8:

It favors those who happened to be born with the right body. Having free time and determination to train really hard isn’t enough to become a top level athlete.

I was sloppy when I conflated duelling and sword-use. Duelling is a whole separate set of rules, and I was implicitly including all the rigamarole with seconds and exchanging challenges, etc. So, if we were talking about an environment where people were engaging in code duello one would expect the person being challenged to have the choice of weapon. That’s quite a clever bit of game-theory, isn’t it? So, in my hypothetical world, where someone who’s athletic and good with a sword and pistol, challenges someone who’s not, they may wind up playing a life and death bout of Mario Kart. Obviously, anyone who was challenged would generally try to play to their strongest suit.

And I can’t even support rhetoric as a means for settling disputes (somebody who is a great orator can potentially get away with abusing somebody who is shy and bad at oratory)

But that’s the balance of the thing! If you were challenging someone you knew was a great speaker, you’d expect them to choose that as their weapon. And, if you were not a great speaker, you’d probably do best not to challenge them. That was why De Rohan cheated to get out of duelling Voltaire – even though Voltaire was mostly known as a wit and a writer, he was young and energetic and less dissipated; he wasn’t confident he could win at either. And I’m quite sure Voltaire would have kicked ass at Mario Kart. And you’d have to be a Trump-level idiot to get into a duel of rhetoric with Voltaire – although the resulting defeat would probably have gone down in history!

The rule being that the challenged chooses the weapon, there were bravoes who would try to draw a challenge, so they could fight in their strong suit.

A society where “might makes right” is not fair or pleasant to live in.

I don’t believe there has ever been a society that is not “might makes right” so I am not sure anyone has experienced anything else.

Marcus,

It was an absolute pleasure having you attend our swordsmithing school. Thank you for documenting your experience day-by-day on this blog. I will be sharing it shortly.

As a teacher of the subject, I feel I would be remiss to not mention a couple of technical error in commentary.

Regarding bronze and early iron, iron was not inferior, it simply is not appreciably harder than bronze. However, the tin need to make bronze was relatively scarce, making it a strategic resource. Iron ore was relatively abundant, but one needed to the technology to refine it.

Regarding, coal and charcoal: charcoal was the first and primary fuel source for metalworking for thousands of years. Coal was not used until much later. Coal is usually also a dirtier fuel, often containing sulfur. Carbon being absorbed into iron happens as a product of the atmosphere of the fire regardless of the fuel. Specifically, carbon is absorbed into iron as carbon-monoxide in a reducing atmosphere fire.

dragonflyforge@#15:

Regarding bronze and early iron, iron was not inferior, it simply is not appreciably harder than bronze. However, the tin need to make bronze was relatively scarce, making it a strategic resource. Iron ore was relatively abundant, but one needed to the technology to refine it.

Regarding, coal and charcoal: charcoal was the first and primary fuel source for metalworking for thousands of years. Coal was not used until much later. Coal is usually also a dirtier fuel, often containing sulfur. Carbon being absorbed into iron happens as a product of the atmosphere of the fire regardless of the fuel. Specifically, carbon is absorbed into iron as carbon-monoxide in a reducing atmosphere fire.

I remember you explained that, and I mangled my summary. Correction much appreciated!

I’m going to be building a sharpening bench in the next week (I hope) and will be posting walkthroughs on facebook and here, along with all the other build-out stuff as I am getting things ready in my shop.