If you’re like most of us, you buy a variety of surfactant products: for your dishes, for your body, for your clothes – some of them are quite expensive. Most of them are made of the cheapest possible stuff. It’s not really hard to do better than the manufacturers do. It’s also fun to learn how to read the ingredients of soaps in hotels and stores – yeah, that “vegan” soap bar with the “sodium tallowate” in it? That’s beef fat.

First, let me get something out of the way: the scene in Fight Club where Tyler puts lye on Narrator’s hand – that’s not how lye behaves (that was baking soda and vinegar) Lye is dangerous but it’s not that bad: if you get it on your hand, wash it off. Splash some vinegar on it to neutralize it if you want to. My worst lye “incident” was when I picked up a bottle of lye beads by the cap (don’t do that) and the bottle dropped to the floor, scattering lye beads all over my kitchen. They promptly melted from the humidity, and I spent 2 hours on my knees with cider vinegar and paper towels. If you want to be really paranoid, make sure you have a gallon of vinegar handy in case you need to neutralize a bit of lye, and work in a well-ventilated space.

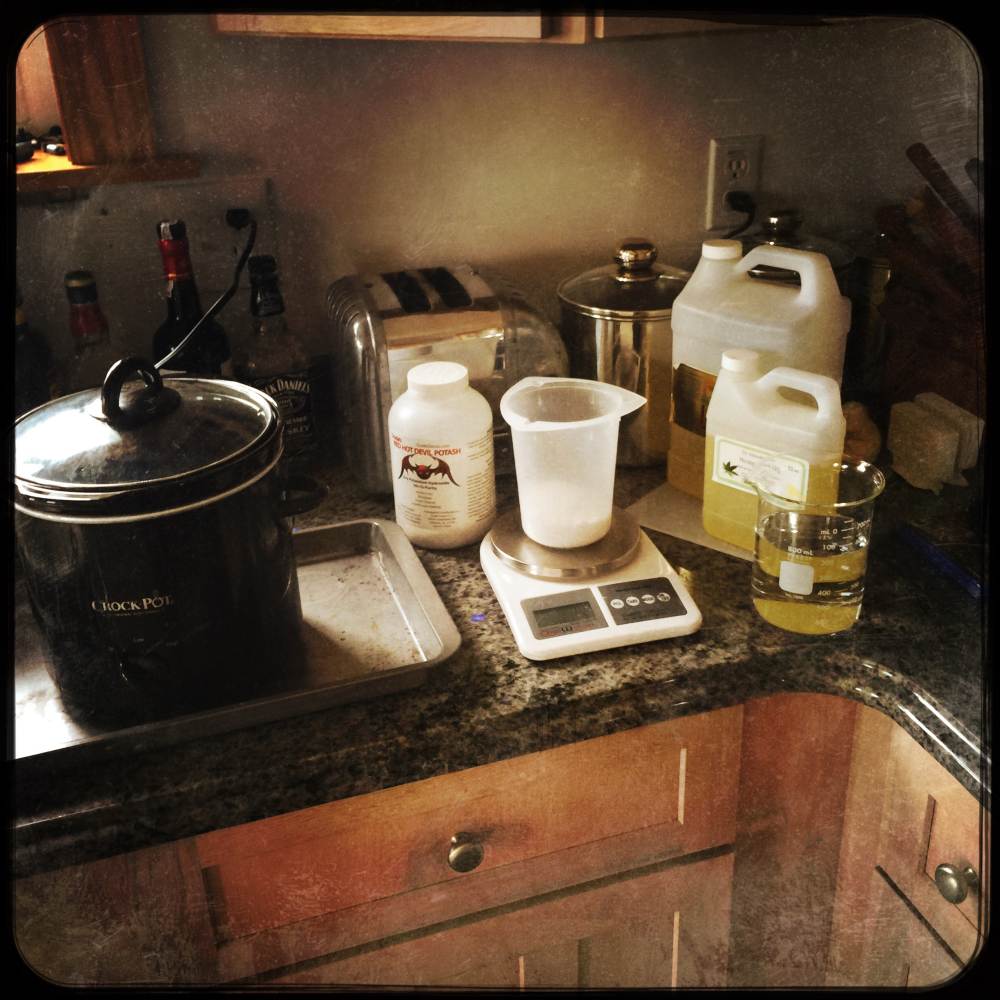

Ready to go

You’ll need oils, potash (I get Red Devil on Amazon) Note: for liquid soap, you use potash instead of lye. A crock pot helps, though you can also cook it in a big pot on very low heat. A good scale is necessary; the quantities  are critical and make the difference between goo and soap, or soap that bleaches the color out of your hair. You may also want a phenothalien indicator so you can test to see if your soap is too basic. I am also a huge fan of tri-pour polypropylene labware – it’s cheap, cleans up great, nothing will stick to it, etc.

are critical and make the difference between goo and soap, or soap that bleaches the color out of your hair. You may also want a phenothalien indicator so you can test to see if your soap is too basic. I am also a huge fan of tri-pour polypropylene labware – it’s cheap, cleans up great, nothing will stick to it, etc.

Then you need a recipe. That’s easy too. Mark if you’re making a liquid or a solid soap, figure out quantities that work for you, and calculate the potash and water based on the amount of oil. There are lots of good saponification calculators on the web. (I use the brambleberry for liquid soap, and the soap guild’s for solid) If you want more detailed instructions than these, this is a great walkthrough on liquid soap-making.

I am mostly writing this to encourage you to do it yourself. When I was a kid, my parents didn’t discourage me from doing stuff just because it was mildly dangerous – they realized that some day I was going to go get a job and drive to work and, if you think about it, that’s what kills you (that, and smoking!) not messing with chemicals. If I had kids I’d probably host “craft sunday” and make something each week. Teach the little rotters how to be careful with something minor like lye and maybe they’ll listen when you tell them that, no, seriously, gasoline is the most dangerous substance you’ll encounter on a regular basis.

Mixing ingredients at trace

Once you’ve mixed your potash and water and it’s dissolved and cleared, let your oils come up to temperature (low!) in a crock pot. Then gently dump the potash/water mix into the oil while stirring. Congratulations, you’ve made soap.

The rest of the process is all about letting the soap saponify, which is basically the sodium ions locking into the fats, which requires heat and moisture and time. Then for solid soaps you let the water evaporate out, and for liquid soaps you dilute it so it doesn’t turn into a hard lump of soap jello.

As your soap cooks (this takes about 4 hours, so I did mine in the morning then worked on other stuff and went and checked on it every half hour) Oh – here’s a hint! Do you see the tray under the crock pot? Soap bubbles a lot and it wants to get out of the pot and walk around your kitchen.

The soap will go through a variety of stages. Most soap-makers have names for each stage. “Trace” – the initial mix when it goes non-newtonian and turns thick like whipping cream. I call this the “phlegm” stage – when it gets clear and foamy and sort of separates.

Phlegm stage

That’s the fats that haven’t unzipped and saponified, floating atop the saponified fats. You need to keep mixing it periodically.

Then there’s the “expansion” stage, which I didn’t photograph because I was too busy trying to keep the soap in the cooker. At a certain point the moisture level will go down and it’ll start to gel. At that point, the bubbles get profuse and it may try to leap into your lap.

Finally, it will gel down to a saponified stage:

gel stage

You can see I’ve managed to get soap all over the crock pot and down the sides. This is normal. The funny thing is: it washes off. It’s soap.

Once you’ve got it at that stage you take a larger pot, boil up some water – I use about a quart, with 2 tablespoons of boraxo in it to neutralize any remaining caustic base, then dump it in and dilute the soap into a nice liquid happy mass.

Diluting and neutralizing the soap

Now, if you didn’t dilute it enough it’ll set up like jello when it cools. That’s fine – just store it that way and reconstitute it into liquid later by dumping it into boiling water and stirring it up. I usually add enough water to make about a gallon of soap, such that it won’t solidify.

Soap ready to store – I swear those aren’t samples of, you know…

I usually disinfect my storage bottles by swirling some everclear in them and dumping it, before I pour off the soap. Leave the lids on loosely so the bottles won’t crush as it cools, then screw the lids down once it’s room temperature.

Some soap makers add color at this stage, and scent. I leave mine to sit in the basement in the dark for storage (it’ll keep for a year or two easily*) When I am making something that requires a liquid soap base I just add the scent and dilute it further as necessary, when I am ready to use it.

Then, clean up the mess!

Cleanup time

Use dish detergent to clean up your soap mess (joy, palmolive, etc) – fresh soap is not fully converted and it’s not ready to combine enthusiastically with water, yet.

Again, if I had kids present, I’d totally teach them this kind of stuff because it’s a good safe way to talk about weighing things, the physics of combining chemicals (two liters of hydrogen gas combine neatly with one liter of oxygen in a very loud way! but it’s safer to demonstrate with soap) And you can emphasize the importance of not getting stuff all over the place while you’re working because you’re the one who’s going to have to clean it all up again, anyway.

Right now I am washing my clothes in hemp/castor oil soap scented with bay rum, benzoin, and frankincense.** What about you?

(* after sitting for a couple months if your soap smells rancid – put the cap back on and throw the whole thing away, don’t try to dump it because apparently you have some kind of bacteria or fungus that can live in soap and you want to minimize its chance of taking up long-term residence in your kitchen! This has never happened to me, by the way – so if you do find something living in your soap, you’ve either made your soap wrong and too many fats got through the process, or you’ve got a publication worthy of Lenski)

(** we’ll talk about scents some other time, ok?)

I’m in the process of moving. My new apartment will have a small back yard where I can try my hand at soap making, so I love reading these posts.

This *is* fun and way cool.

Your soap bottles, and the color, remind me of teaching dyeing. Vat dyes (like indigo) are put in a pot and then you reduce the pot with the use of lye. The color… is remarkably similar to… well, urine. At this point in the class, NO ONE wants to put a skein of perfectly good yarn in there. :-) It’s hilarious. The happy ending is when you pull the skein out and the reaction with oxygen takes place. A beautiful blue appears by the “magic” of chemistry!

kestrel@#2:

OOOOOOOOOOOOOO that sounds SO COOOOOOL.

(Runs off to search youtube for video of the reaction)

The color… is remarkably similar to… well, urine

I’d say it’s more like “beer” ;)

@Marcus: uh… no, I can assure you. No one will think that is beer, not in real life. It really and truly does look like a big pot full of urine. Unless, of course, you’ve seen it before. When I saw your soap in the bottles my first thought was, “That looks just like a pot of indigo!”. :-D

Wait a minute. Do you mean… processed beer? Because in that case I totally agree.

Gregory in Seattle@#1:

Thanks for the feedback! I’m conscious there’s a line between “interesting” and “self-absorbed” and I’m trying to dance on it.

Also, it’s hard to hide our collective hive-mind social justice agenda in a posting about making soap, ya kno?

kestrel@#5:

Do you mean… processed beer?

Could be Stella Artois.

Must be my day for being a pedant. In this context I think you mean potassium. Sodium for solid soaps where you’ve used lye. I love all the craft related posts by the way. Especially since they often appeal to my inner chemist.

Rob@#8:

Well, I was referring to a bar of solid soap that I saw at a shi-shi store in Napa… So it would have been sodium, I believe. Soap makers use sodium hydroxide (lye) for solid soap and potassium hydroxide (potash) for liquid, I am not sure why, though.

I appreciate the feedback on the craft-related posts. I’m trying to balance my stream of consciousness and I don’t want to be too political, or too crafty, or too weird. So it helps to know.

I’ve got a short trip coming up but when I get back I think I’ll take you all through a series of posts as I make some Hand Soap.

Soap in Florida is commonly attacked by mold and bacteria. Black stuff growing in any cracks, and a gray overcast are pretty common if you leave it out for a few weeks without being used. That and roaches will eat bar soap. And certain soft plastics. Liquid soap in a plastic container gets mold around the caps but can be rehabilitated by a running it under water and a quick scrub.

It’s a jungle down here. It isn’t just the humidity. The woods are alive with molds, lichens, and bacterial colonies. The darker side of a friend’s house turned bright red with mold after three weeks of twice daily, or better, rain. One day it looked fine and the next the whole side was red. It was such a bright shade he at first thought someone had vandalized the building with spray-paint. Washing with bleach fortified with a wetting agent and mild detergent, and a long-handled scrub brush rectified the problem … for now. It’s a jungle down here.

Marcus @9, I’m not sure why (it’s going to bug me till I find out), but the sodium salt of fatty acids tends to crystallise whereas the potassium salt doesn’t. Hence one soap goes hard while the other doesn’t. Incidentally, read “The slow regard for silent things” by Patrick Rothfuss for a most excellent description of making soap from scratch.

lorn@#10:

Most soap-makers “superfat” their soap – which means they have more oil than the amount of lye will be able to saponify. If everything is measured right, you’ll wind up with soap that is crystalline and hard, and a good surfactant, but which also has unconverted fats still in it. Superfatted soap is how you get wonderful creamy skin afterward: basically you’re washing at the same time as you’re rubbing cocoa butter (or beef tallow or whatever) onto your skin.

I usually superfat slightly with my bar soap (which mice will cheerfully eat even if it’s not superfatted) and go right on the line with liquid soap. When I produce a final product with my liquid soap I usually add either a small bit of germaben (broad spectrum antifungal) or something containing alcohol, e.g: bay rum. Bay rum shampoo is mighty fine and it’s antibacterial!

I can’t imagine what it’s like to have fungus eating everything. :/ I grew up in Baltimore, which is usually 100% humidity all summer, but at least things used to dry out in the winter.

Rob@#11:

Aha! Well if I understand what’s going on the lipids in the fat are getting broken apart into long chains and sort of curl up into a mat, somewhat like gelatine. It’s possible that the potassium doesn’t make it curl up and gel? I’m interested to know, too – mostly because I like mountains of trivia.

Now, if you’re into materials chemistry, maybe I’ll bestir myself to make a batch of turkish delight and post the process and recipe. I have an old version on my website but for various reasons I want to update the photos. Anyhow, I believe that caramel works by converting the sugars into long chains and driving the water out of the sugar. And I believe cornstarch boiled in water produces long starch-chains that stick to water. What happens when you mix those at exactly the right stage in that process? Turkish delight. It’s how gumdrops and pretty much every gooey sweet thing work.

The Rothfuss book: I started on it, but I fell asleep a ways in and never picked it up again. The Kvothe books held my attention but I felt TSROPT was a bit too precious. If you’re an insomniac, btw, try the narrated version. Rothfuss’ voice is very soothing. Nearly hypnotic.

Hmmmmm Turkish delight. My personal crack cocaine, which is why my partner doesn’t allow it in the house. Apparently she loves me and doesn’t want we to die of obesity or type II diabetes. Spoil sport. I loved Slow regard. Rothfuss has an incredibly evocative way of writing and differentiates his characters really well. Which is probably why he’s taking so freaking long to release the third Kvothe book! Rothfuss, if you’re reading this, get on with it or my friends and I are coming from New Zealand to camp on your lawn. The book is slow because of the recursive and OCD nature of Auri’s behaviour, which the book only hints at the reasons for.