The US empire was forged in Pittsburgh, and in Bethlehem, and Baltimore’s Sparrow’s Point. The plant at Bethlehem was huge; I spent a day wandering inside the year before it was finally torn down.

A gigantic overhead gantry ran out into the plant yard where steel was poured into gigantic molds. The turrets on the battleship New Jersey were castings, not pieces welded together; the overhead steel-carrying system that poured 2500+F steel into the molds could carry a liquid battleship turret’s worth of material in a single operation. At the other end of the plant were the great fires that melted the metal and kept it liquid. The great carrying system was called the Hoover-Mason Trestle; it was the World War II-era industrial automation of the mill. During the great wars, so many bodies were needed to make the guns and turrets that women were pressed into service at the steel plant; there was Rosie the Riveter but also Alice the Oxy-Acetylene torch artist.

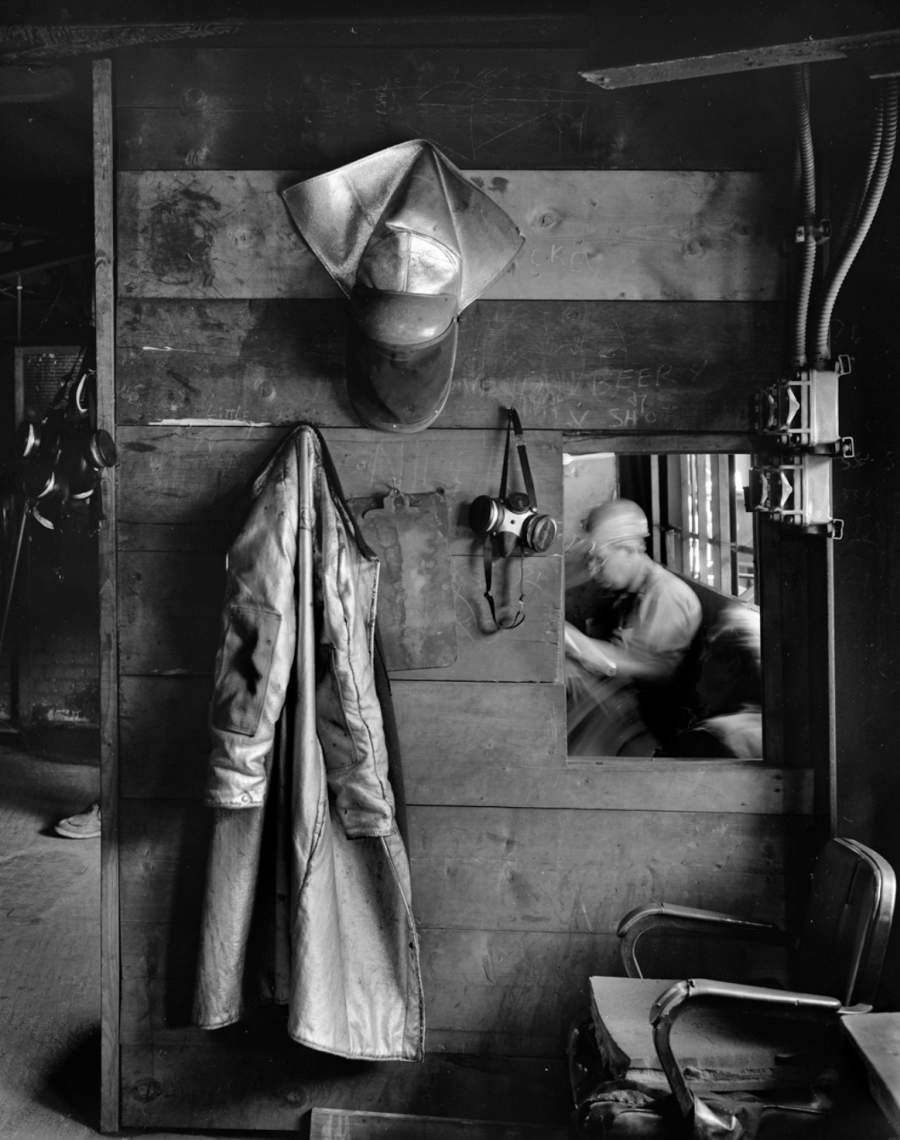

Bethlehem in 1905

They didn’t have safety equipment, except for the stuff that was needed to ensure survival. Without a doubt women came out of the plant with their lungs scarred and their lives shortened, their joints torn with heavy metals and their livers cancerous from cadmium.

What happened to US Steel is two-fold: people began to realize how long-term dangerous it was, how it shortened your life and – like coal mining in the Appalachians – produced an aging coterie of wounded people who wanted medical assistance. Second, the wars ended, so the war economy shifted, and the plants could drop to more reasonable production demands. That gave the plant owners time to automate some of the jobs, reduce the size of the work-force, mechanize. In the Appalachians the same was happening to coal: it was no longer a job of digging underground and pulling out carts with donkeys in the dark – now a dozen men with blasting jelly and strip-mining gear would simply scrape the top off a mountain, then put it back with the 6-foot-thick ‘A’ line of coal gone. Automate, mechanize, pressure the workforce and keep the unions from getting too strong.

What happened to US Steel is two-fold: people began to realize how long-term dangerous it was, how it shortened your life and – like coal mining in the Appalachians – produced an aging coterie of wounded people who wanted medical assistance. Second, the wars ended, so the war economy shifted, and the plants could drop to more reasonable production demands. That gave the plant owners time to automate some of the jobs, reduce the size of the work-force, mechanize. In the Appalachians the same was happening to coal: it was no longer a job of digging underground and pulling out carts with donkeys in the dark – now a dozen men with blasting jelly and strip-mining gear would simply scrape the top off a mountain, then put it back with the 6-foot-thick ‘A’ line of coal gone. Automate, mechanize, pressure the workforce and keep the unions from getting too strong.

Bethlehem in the 1970s. Empty; the tools are all put down where they were being used.

Then there were the 80s, where the demand for steel dropped, but more importantly, the Wall St investment bankers invented a thing called “asset stripping.” It had nothing to do with steel, the steel business, or foreign competition; here’s how it worked: you find a company that has a lot of cash in the bank, perhaps a well-funded pension plan. Then, you borrow enough money to buy the company, break it apart, sell it, and use the cash it had in the bank to pay for buying it. It was a simple assets to revenues game: buy it, strip it, flip it, and move on to the next one. All you have to do is find a company that has made the mistake of being worth more than you can buy it for.

I remember in the 80s when Sparrows Point in Baltimore shut down – they just couldn’t keep it profitable, the new owners said, because the pension plan was too high and the workers would have to agree to a reduction if they wanted the plant to stay open. It didn’t matter: the spiral of layoffs continued.

Air pumps at the old Bethlehem plant.

Meanwhile, the money went other places. It was cheaper to make the steel in China, and since the military economy had changed there was no obvious strategic problem with outsourcing production. Doubtless someone in Washington also realized that the days when giant lines of steel machines clawed at each other were over. There would not be tens of thousands of tanks, there would be a couple hundred but they’d be very good, very expensive, and they’d need a fraction of the production capacity.

What killed the steel factories? Capitalism, changes in how the US fights its wars, and the fact that the Chinese were able to make things for less. Also, the Chinese were building plants based on new technology; they didn’t have the cost of replacing existing infrastructure, which can be more expensive than starting from scratch.

Bethlehem, before the fire went out forever.

The money wasn’t there, so the industry consolidated. Another problem was the cost of moving materials around – raw ore wasn’t coming from nearby any more, it was coming in by boat to Philadelphia from overseas. The industry was balanced on a fairly thin margin that got thinner and thinner. By the time the companies realized what was happening, they had a choice: re-build their plants completely in order to take advantage of more automation and drive their bottom line cost down, or shut down because they could not compete. The problem was, they had waited until the money was running out and there weren’t the necessary hundreds of millions of dollars to re-invent the US steel industry.

Don’t blame the workers. Or, for that matter, don’t blame the Chinese. The blame goes to the steel companies, that didn’t re-invest in modernizing their equipment, so they wound up with factories that could not compete. The blame goes to the steel companies’ executives, who should have seen that coming, but who preferred to cash out and let the asset strippers and Wall Street gamblers take over. The blame goes to the energy crisis of the 70s, when shipping ore got just a little bit too much more expensive. There’s lots of blame to go around – but nobody “stole” America’s steel jobs: America pissed them away.

[source: Baltimore Sun]

The current state of the art processes are mostly electrical arcs melting powdered steel into molds that have been designed on computers and made on CNC machines. The US has a lot of plants that work that way, actually, but when Americans think of steel, that’s not what they remember.

The death of the steel industry – driven by capitalist forces and fine profit margins – destroyed lives. We remember those, too. There were lots of Americans that trusted their company pension, which vanished. There were lots of Americans that trusted that the company would be there, and not be mis-managed to oblivion or shut down so that some Wall Street lawyer could buy another house in the Hamptons.

While he waited, the plant’s last chance evaporated. A competitor bought the facility’s most valuable mill for spare parts. Everything else would be sold off in pieces or demolished, the land redeveloped, likely for industrial uses such as a marine terminal.

“That’s it, Deb,” he told his wife after hearing the news at a December union meeting. “It’s gone. It’s gone.”

The months after the layoff changed him. He was quieter. Stopped telling jokes. Slept less. Sometimes as he struggled on the computer “he would scream and hold his head,” his wife says.

His remaining hope rested on a welding course that was to begin the first Monday in January. The Friday before, he called Pennsylvania’s workforce agency to make sure that his funding was set. Not yet, his rep said.

The next day, when Debby Jennings popped out for a blood test, her husband walked to the shed, put a shotgun under his chin and pulled the trigger.

There’s a real human cost when companies shut down, when industries are screwed up so badly that they become prey for corporate raiders. You can’t expect coal miners to understand the big businesses, you can’t expect the steel-workers to foresee what a change in the cost of diesel fuel will do to the cost of ore shipments; they trusted the executives.

And they’re still being played for suckers: “we’re going to bring back steel,” some say. But they know they’re lying. They’re just farming the workers for votes.

I feel for the steel-workers. They had horrible working conditions and dangerous jobs, but they did them. So, afterward, they felt proud of surviving and accomplishing what they did. [meet you in hell]

As one iron “puddler” described his job: “For twenty-five minutes while the boil goes on I stir it constantly with my long iron rabble. A cook stirring gravy to keep it from scorching in the skillet is done in two minutes and backs off blinking, sweating, and choking, having finished the hardest job of getting dinner. But my hardest job lasts not two minutes but the better part of half an hour. My spoon weighs twenty-five pounds, my porridge is pasty iron, and the heat of my kitchen is so great that if my body was not hardened to it, the ordeal would drop me in my tracks.”

“Little spikes of pure iron like frost spars glow white-hot and stick out of the churning slag. These must be stirred under at once. I am like some frantic baker in the inferno kneading a batch of iron bread for the devil’s breakfast.” Reading such accounts lends credence to the generally accepted notion that in the steel industry, by the time a laborer reached the age of forty he was essentially “all wore out.”

Some of those beautiful photos are by Joseph E.B. Elliot [jee]. Elliot realized the steel plants were dying and got busy with his camera before it happened.

The Baltimore Sun’s poignant article about the swansong of the steel industry in Baltimore is [here]

The Morning Call analysis of why Bethlehem Steel collapsed [mcc]

Century Aluminum Executive Backs Trump’s International Tariff Plan

So he starts by blaming their lack of competitiveness on cheating by foreign countries in the way of subsidization, but if you actually pay attention to what he is saying, he admits that their plants are not using the most competitive technology.

Reginald Selkirk@#1:

bring back around 300 jobs, and invest over a hundred-million dollars in that plant to restart it

You’re definitely right that they’re talking about a state-of-the-art plant. Probably going to be doing powdered metal processing, CAD, maybe 3D printing: look at the size of the proposed work-force – 300 jobs. That’s pretty much nothing. All they’re going to use the old plant for is the walls – assuming they’re not full of toxic materials.

And if it’s powdered metal, CAD and CNC then it’s a different skill-set from the old metal-workers’ jobs. They try, sometimes, to retrain them to use the new machines but really, it’s the kind of thing a 14-year-old can do, not some senior machinist who knows how to use machines from the early 20th century.

Also, I know you know this, but:

So he starts by blaming their lack of competitiveness on cheating by foreign countries in the way of subsidization[…]

The US’ massive expenditures on its military have always amounted to a huge subsidy to multiple industries – aerospace, steel, chemical … Every artillery round fired in Syria is $1000 for American steel and chemical and transport industries. And those are the basic munitions; it goes up fast from there.

But take, for example, an artillery shell. In terms of steel and chemicals a $1000 dumb 155mm creates as much jobs as a $70,000 M982 “smart round” – the cost difference in the M982 goes to the aerospace industry companies (who are doing just fine) (for now).

One of the other factors that has affected American industry is the DoD no longer makes a fleet of battleships out of steel, they make a single Zumwalt-class frigate out of aluminum. Instead of using $500 million in steel they use $100 million in aluminum and the rest of the manufacturing is high-tech processes. America’s big spend has shifted permanently away from great big piles of metal toward smaller numbers of piles of very expensive metal and tech. I’d be surprised if an M-1 Abrams tank uses much more steel than an old WWII Sherman did: the difference in weight is the ceramic and depleted uranium sheets inside the armor and the difference in cost is the crazy complex battlefield systems and high tech stabilizers and sights.

If you look at how the US steel industry ballooned and busted there’s a good case that can be made that war economy/military spending had a lot to do with the demand cycle that helped make the boom/bust happen. US aerospace industry is where that money went. If we ever stop spending so much money on wars, those guys are going to collapse in on themselves exactly like the steel companies did. Only this time it’ll be vocal members of the former middle class technological elite.

Retirement savings seem like one of capitalists’ favorite targets when attempting to steal from workers. Personally, I have come to the point where I don’t trust anybody. Not even countries.

Where I live, it’s the country that pays people their pensions. My mother spent her entire life working and paying taxes, and the country’s leaders simply fucked her. In Latvia there’s very little correlation between how much taxes you paid during your lifetime and how large your pension will be. Politicians who created the system made it inherently unfair to ensure that they got large pensions. For the rest of the population the amount of money they get depends on luck—the main criterion for determining how large your pension will be is the year you were born. Latvian politicians who were in charge in 1996 passed a law that says that for people who worked and paid their taxes to the Soviet state their pension will depend on how large their salary was in the 1996 to 1999 period. It doesn’t matter how much you earned for the rest of your lifetime, all that matters is how much you earned during the all important four year period. Of course the politicians who passed this law were earning really large salaries during these all important years. My mother got unlucky though. I was born in 1992, which is why in 1996 she was only working part time with little income (after all, she had to look after a small child).

And politicians who were in charge when the 2008 year crisis hit passed another unfair law. People who retired before 2008 got significantly larger pensions than people who retired shortly after 2008. When the crisis hit, country’s tax income decreased. Politicians couldn’t legally reduce pensions of people who were already retired, so instead they decided to reduce the pensions of those who were to retire in the years shortly after 2008. My mother got unlucky once again, because she retired after 2008. The end result was that, after legally retiring, my mother simply had to start a new business, because there was no way how she could survive with the little amount of money the country was willing to give her.

And recently the bank lobby managed to make our politicians pass yet another annoying law, which says that now everybody is forced to have a retirement savings account in one of Latvian banks (options to choose from are very limited). If your retirement plan ends up losing money or your chosen bank goes bankrupt, well, bad luck for you.

Sheffield, which of course is famous for it’s steel, still produces a lot of steel, but it’s all specialised small tonnage, but far more valuable.Things like medical and food grade piping, implants like hip replacements which are made individually, scalpel blades etc. Most of this production requires far fewer jobs than the bulk steel producers needed.

Ieva Skrebele@#4:

Where I live, it’s the country that pays people their pensions. My mother spent her entire life working and paying taxes, and the country’s leaders simply fucked her. In Latvia there’s very little correlation between how much taxes you paid during your lifetime and how large your pension will be.

In the US the idea is (because so many company pensions were getting “re-negotiated” when the time came to pay out) that the government would require people to invest in a retirement plan: social security. You pay in a percentage while you’re working and when you retire, you get it back with some interest. It’s actually a pretty reasonable idea, in my opinion.

Or, it would have been, except that the government allowed itself to borrow against it and now the republicans are calling it an “entitlement” (no, motherfucker, that’s my money!) and want to stop paying it out. In other words they not only want to cancel the pittance retirees are supposed to be living on, they want to effectively turn it into a tax on being gainfully employed.

There is something else wrong with social security: I’ve put almost exactly the same amount of money in my personal retirement account as I have paid in to social security. My social security payment on retirement will be about $900/month if I ever actually get any. My personal retirement account is large enough that I expect a comfortable retirement with plenty of money. Somehow the government, which claimed to be a wise custodian for my money – well, it wasn’t.

You are wise not to trust politicians. Anarchists have been trying to get people to understand this for thousands of years: politicians will screw you. Because no truly decent person wants to be a politician, anyone who wants to be a politician is at least a sneak and a liar, and it goes downhill from there.

If your retirement plan ends up losing money or your chosen bank goes bankrupt, well, bad luck for you.

Not to bring up a sore subject, but sometimes I think mass shootings aren’t a bad idea. Maybe politicians would be a little more careful about doing this kind of shit if every so often one of the people whose lives they ruined walked up to them and knifed them a bit. Not completely. Just a bit. “Pour encourager les autres.”

jazzlet@#5:

Sheffield, which of course is famous for it’s steel, still produces a lot of steel, but it’s all specialised small tonnage, but far more valuable.

Sheffield was producing world-renowned high quality steel before the industrial revolution, back when it was all gravity-based crucible steel separation (The same metallurgy the Japanese used for making their justly praised swords) – it was a very laborious process and time and resource-intensive. But not manpower intensive, really, compared to the great war-machine making steel plants that came after the industrial revolution.

It’s good to see that Sheffield has survived in the steel-making world. When I was a kid I had a dagger that was stamped “Sheffield steel” on it. I gotta say, it took a lot of work to snap that blade, but I eventually got the job done…

What all this points to, for me, is a boom/bust cycle that is a result of militarism and government subsidy for defense. I quoted a chunk from Landes’ The Unbound Prometheus and I will admit that it has tremendously influenced my thinking on this matter. I highly recommend that book to anyone who is interested in this sort of stuff.

Steel-making nowadays is (barring mad badgers that want to hammer on the stuff) a process that involves computers more than crucibles, CNC more than bessemer, and there’s a huge industry in breaking old warships apart so they can be re-smelted into useful objects. There is so much tonnage of steel in old warships – steel that probably first melted in Pittsburgh or Bethlehem or Baltimore – all over the world.

When I get into this stuff I don’t know if I should post about it, or not. I could drone on and on about it. The cycle of industrial life is beautiful and sad to me.

There have been reports that some of the WWII wrecks of capital ships have vanished from the ocean floor, having been secretly salvaged and recycled. Probably not the worst thing that could happen to them, but unfortunate for historians of the period. Also upsetting to people who think of those wrecks as the graveyards of their sailors.

My brother spent his entire career in the steel industry, and saw all the changes you’ve described from the inside. He was a plant electrical engineer so he rolled with the punches and did well, ending up designing the control systems for those remelting/recycling plants. Steel is still around in the US but it’s very different now, and many of the plants are foreign-owned. Yay globalism?

Elliot realized the steel plants were dying and got busy with his camera …

How did a photographer catch on to what thousands of industrial professionals missed?

Also upsetting to people who think of those wrecks as the graveyards of their sailors.

The steel those ships were made of, and the ships themselves, were already the graves of a number of people, before they even sailed. Sure, they did not contain actual human remains, but at this point the wrecks probably no longer do, either.

Theoretically I’m in favor of states taking charge of pensions. Otherwise you are bound to end up with lots of old people who are unable to work and have no money at all. Well, you might as well turn it into guaranteed minimum income rather than pension, because, in my opinion, a society shouldn’t allow extreme poverty to exist at all (regardless of how old the unemployed person is). That’s all theoretically. Unfortunately, in real life I have witnessed plenty of examples where politicians messed up the system. Yet regardless of their shortcomings, governments seem to actually have a better track record than banks and private companies. At least states don’t bankrupt as often as banks do.

Another reason why states should be taking charge of pensions is that states can use this money for useful purposes, they can invest it. Compare that with banks, which instead use whatever money they get their hands on in order to inflate bubbles. Well, I guess I hate banks even more than states. All banks do is inflate bubbles and ask for bailouts.

Republicans? Weren’t they against taxes? It would make sense if republicans wanted to completely abolish the system (namely, people get to keep all their money). The way it sounds for me is that republicans want to create a new tax (namely, state takes people’s money and keeps it, which is the very definition of a tax).

@#8

I don’t get people romanticizing human remains. They are nothing but a collection of molecules. The whole modern burial industry is causing harm for the environment (cutting down trees to make coffins) and wasting real estate (cemetery land could be used for something more useful). It would be more reasonable to just approach this whole issue rationally. Dead human bodies could be useful (organ transplantations, scientific experiments), but instead they are turned into a disposal problem. Personally I’m planning to just let doctors and scientists deal with my dead remains, thus saving my family members all the burial expenses. As for ship wrecks, after historians have gotten a chance to record and recover everything useful, it actually would make sense to salvage and recycle the leftovers.

I like cemeteries, especially old ones. They’re peaceful.

@#13

Well, if cemeteries are simply parks with a couple of tombstones here and there, then that’s fine, after all, parks are essential in every city.

However, it’s not always so nice. In the city where I live, old graveyards are a large problem. There are multiple graveyards quite close to the city center (some are actually inside the area that’s considered the city center). These cemeteries are old enough that the dead have no remaining living relatives. Thus nobody is going there to take regular care of the tombstones and crosses. By now, wooden crosses are rotting and falling apart, gravestones are overgrowing with lichen, weeds and bushes. Simultaneously the graveyards are not old enough for politicians to simply send bulldozers there. It could be possible to turn these cemeteries into normal parks—remove all the crosses and tombstones, cut down bushes and small trees, make new roads over where the graves are. But, whoops, the cemeteries aren’t old enough, politicians don’t even dare proposing that. These cemeteries are very dark, overgrown, with little sunlight shining through the tree leaves. And they make really bad public parks. Sure, dog owners who live nearby go there for walks, but only because there are no other parks nearby.

One such graveyard was located right next to my school, it was on the opposite side of the street. When I was a child, after school I used to go there to play, I remember playing with my classmates right next to the tombstones. Occasionally I also went there alone after school, after all that was the only park-like thing located between my school and my home. When I was about eight years old, I was once approached by a man in that cemetery. He had his pants unzipped, his penis out of his pants and he asked me for a handjob. When he approached me, I was looking up at his face and at first I didn’t understand what he was asking. Then I looked down, saw the penis, said “yuck”, and ran away. In case you are wondering, no, I wasn’t traumatized, I wasn’t scared, I wasn’t hurt. At that time I had no understanding about concepts like “sex” or “handjob.” Back then I didn’t tell my mother about this incident, because I had no clue that it was important or that I had experienced sexual assault. I still remember this incident only because it seemed very weird at the time, I realized what had happened only several years later. That cemetery was dark, overgrown, with small trees and bushes obscuring the view. It was also pretty empty, very few people liked going there for walks. Sexual predators cannot walk around with unzipped pants in normal parks. That guy could do that in that cemetery only because the place itself was badly designed for a park. I’m pretty certain that I wasn’t the only child he approached. Incidentally, a couple of years ago city authorities built a fence around that graveyard. Now that graveyard is not only wasted real estate, it is also encircled with a fence to ensure that children don’t go in there. Which is why, in my opinion, it would be better to just send the bulldozers instead of building fences.

Pierce R. Butler@#9:

How did a photographer catch on to what thousands of industrial professionals missed?

Probably obvious enough to an outsider. I remember the endless news about job cuts at Sparrows Point – if I had cared enough to think about it, I would have seen what was coming, too.

It reminds me of O. Winston Link, a favorite photographer of mine. He loved steam trains and started photographing them a lot, just in time to chronicle the last steam trains in the US. If you know a train fan, check out any book of Link’s work, it’s pretty gorgeous. Link saw it coming because he was an outsider, and a fan.

I suspect a lot of it’s the “boiling a frog” story (which is not true) – that the frog doesn’t figure out what’s happening if you raise the temperature slowly.

I have a different hypothesis—outside observers just rationally analyze the facts thus noticing a trend and predicting that it will continue in this direction. For people working in the factories it’s a different situation—their personal wellbeing is at stake, therefore they are afraid to even think about the probability that also their factory might go bankrupt. They fear the possibility, they don’t want to think about it, therefore they just deny and choose to ignore the facts. When they notice the symptoms, they try to rationalize them, explain them differently.

Ieva Skrebele@#16:

When they notice the symptoms, they try to rationalize them, explain them differently.

They probably are also aware of whatever the company is doing to save itself. So they may have cause to hope. Wrongly, but they still hope.

Ieva Skrebele:

Which is why, in my opinion, it would be better to just send the bulldozers instead of building fences.

For purely practical reasons, you can afford to spend a little money and effort to appease the sensibilities of a lot people. After all, it’s primo real estate, as you say, so you could do something less controversial than just bulldoze the cemeteries. (I don’t personally object to that, except in that you may be destroying some interesting or valuable artifacts.)

As for myself, I’ve made it clear that I want my body disposed of as economically as possible, and with minimum impact. Currently, that option is cremation. I don’t think rendering down the fats and proteins in human bodies and using them as pet food is safe, or economically viable, or environmentally beneficial, and it seems unlikely that it will ever be. (Using them as feed for farm animals is unsafe because of prion diseases.) So take whatever can be reused, learn what you can (if anything), and burn the rest of the useless husk. Send the ashes to landfill (or keep them, if it helps any; I’m not using that potassium anymore).

Just to be clear, while I don’t object to the bulldozing of cemeteries, I do object to upsetting people unnecessarily.

It’s not that simple. Are you supposed to send an army of government employees to handpick weeds and scrape lichen off tombstones? Moreover, if you want to turn a cemetery into a decent park, you must pave new roads… on top of the graves. In normal parks you generally have plenty of lawns and it’s simple to just keep them neat looking with a standard lawn mower. But it’s not like you can use one of those to get rid of weeds that grow around tombstones. Tombstones, small fences around each grave, raised soil where the graves are—all of those make it impossible to manage cemeteries with the same ease as normal parks. It’s simpler and cheaper to just remove the tombstones and plant a lawn.

This https://i.ytimg.com/vi/jLdKx6buyFo/maxresdefault.jpg is a photo from that graveyard next to my former school. A lawnmower wouldn’t be sufficient to make this kind of place decent looking.

According to Wikipedia: “Each cremation uses about 110 L (28 US gal) of fuel and releases about 240 kg (540 lb) of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Thus, the roughly 1 million bodies that are cremated annually in the United States produce about 240,000 t (270,000 short tons) of carbon dioxide. That’s more CO2 pollution than 22,000 average American homes generate in a year.” And it’s not just CO2, also other environmental pollutants are released. For example, mercury is emitted when a person with dental amalgam fillings is cremated. That doesn’t sound particularly environmentally friendly for me.

Compare that with traditional burial, where dead bodies are pumped full of embalming fluid (formaldehyde, a known carcinogen), put into a casket (often made of tropical hardwood), and buried inside a concrete grave liner.

Where I live, embalming fluids are used less commonly, grave liners don’t exist, and coffins are usually made from cheap local pine wood. Still, cemeteries waste a lot of real estate here, which can be a big problem for cities in some densely inhabited regions.

I’d say that none of tradition Western methods for disposing of dead bodies is environmentally friendly.

Sure, it’s not like I suggested using human remains for pet food. I’m fully aware that this could spread diseases.

But using them as a plant fertilizer could actually work. Here’s a project about decomposing human remains and turning them into nutrient rich soil: https://www.ted.com/talks/katrina_spade_when_i_die_recompose_me

For people who prefer something that resembles burial, there’s the natural burial option: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_burial A body is buried with no embalming and no coffin, therefore it just decomposes and causes no harm for the environment.

Then there’s also such a thing as “meat and bone meal,” which is a product of the rendering industry, basically it is a mixture of finely ground animal bones and slaughter-house waste products. It is used as a fossil-fuel replacement for renewable energy generation, such as generating electricity or using it as fuel in cement kilns. Instead of using fossil fuel in order to cremate people, it could be possible to use human remains themselves as a source of fuel.

There are plenty of useful or at least not environmentally harmful ways how to dispose of dead human bodies. If humans have figured out ways how to dispose of dead cows, why can’t we apply similar methods for disposing of dead human bodies? After all, humans are just animals. For millions of years dead animal bodies posed no environmental problem on this planet. Humans are the only species on this planet, which are causing environmental harm after their death.

Ieva Skribele:

Assuming average American homes are three humans, the cremation of an American is worth 0.7% of their former annual CO2- output. It’s a footnote on their (or my) consumerist life.

I’m firmly in the cremation camp; and in some European countries, I could have my ashes strewn from a plane, over the landscape.

BTW one could also use renewable-generated electricity to cremate somebody, because cremation is flexible demand: if not today, perhaps tomorrow…

wereatheist:

Better than embalming, I guess. But blood and bone makes good fertiliser.

(And it’s not as if the actual dead people care after their death, is it?)

Maybe some of the nitrate will be gone; but the phosphorus and other trace minerals will still exist, so I think cremation ash is good fertilizer, too :)

If I’m not mistaken, there’s even an enhancement to “natural burial”: It’s freezing corpses first, then bury them without coffin.

Freezing/thawing destroys cell walls, giving bacteria much easier entry, and the rot performs like charm.

Of course not. It’s just that actual undead people care about the last impression they might leave.

wereatheist, the nitty-gritty: both you and I think corpses are useful resources.

(Those old factories are corpses, too)

Re-reading this, and seeing some random articles on the closing of Toy R Us, it seems similar. Marcus, are you familiar enough with the business background of Toys R Us to make a comparison?

I see a lot of people blaming millennials (as usual) for not buying toys from the store they grew up buying toys from. The company was purchased and made private in the early 2000s (2006ish I think). It seems to me the company that bought it overpaid and was never able to catch up on the debt,which seems a bit simpler to understand than the methods you describe above, but it also seems, well, dumb.