On July 4, 1776, a bunch of would-be oligarchs declared the independence of the American colonies.

And it worked, for them. The reasons for the revolt were primarily two-fold: 1) their massive wealth was being taxed, and 2) their “freedoms” were being infringed. As I’ve described elsewhere, [stderr] the “freedom” being infringed was that people could be held as chattel. The oligarchs-to-be were dead set against that, because, well, you weren’t going to catch Thomas Jefferson cutting tobacco or picking cotton – hell no. You weren’t going to catch John Hancock paying a fair import duty on his smuggled rum and slaves; that just wasn’t going to happen. George Washington, a land speculator who was one of the largest real estate owners in the colonies – you weren’t going to catch him paying property taxes – never. The colonial would-be oligarchs who were whipping the people to a froth didn’t seem to mention that a British citizen typically paid 10 times what a colonial paid, at that time. Had the revolt just been about taxes, we would have expected the Londoners to throw king George out and appeal to join the colonies.

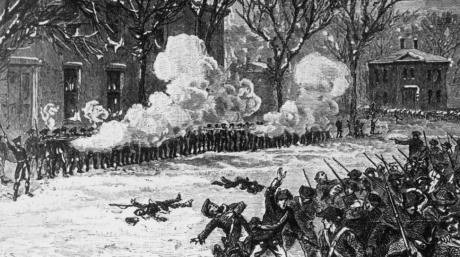

Shay’s rebellion; sort of an American “whiff of grapeshot”

The rest, we know: the Crown Court Lord Chief Justice Mansfield had already hammered the nail in the coffin of slavery in May of 1772; the colonists were not exactly all in favor of independence, but by the time all the fighting and dying was over, there was a new nation, set forth in hypocrisy, with justice toward white property-owning men, and slavery for some. Even early on, the new oligarchs were careful to manipulate the tax system, so that things like alcohol consumption were taxed, but real estate was not; it was mere coincidence that the oligarchs’ long-term wealth was mostly tied up in real estate – within a few years of independence the typical American was paying more taxes than the typical citizen of the British Empire, a state of affairs that resulted in farmers’ rebellions like Shay’s rebellion and the Whiskey rebellion, which were brutally repressed by the new country’s new army. It ought to sound shockingly similar to what happened in France, where a new oligarchy replaced an ageing senescent monarchy, and quickly took on the same airs and vices. In France, the new oligarchy at least had a sense of style and panache and damn near conquered Europe.

It’s a tradition in the US to talk about the political geniuses who wrote the constitution, but that document was barely accepted in its first version, and only was ratified once the slave-owners were able to protect their interests against all comers, embedding the oligarchy into the foundation of the country so thoroughly that a horrible civil war was fought, costing massive lives and damage, without resolving the problem that caused the war in the first place. That was some political genius: creating a constitutional republic that barely survived 100 years without a referendum by mass slaughter! Of course, it’s been mass slaughter all along – the economy of the new oligarchy depended on “free” land garnered by genocide, land which was exploited in the coarsest possible and most ruthless manner; a habit that America’s oligarchs spend vast sums on propaganda to continue. Ironically, today’s oligarchs whip their followers into a frenzy against “immigrants” – when they’re the most successful and red-handed “illegal immigrants” since the Mongols.

A tough old buzzard

As of this writing the US Empire has special forces teams operating in over 70 countries worldwide. That’s the declassified estimate. Imagine the world’s reaction if ISIS had extremely well-trained and armed units, in 70+ countries world-wide, with a huge logistic and intelligence apparatus behind them, spreading ISIS ideology at the tip of a bayonet. Sound too much like moral equivocation for you? ISIS hasn’t bombed Cambodia, yet. Nor North Korea. The war crimes of ISIS are a peccadillo next to the US’. Admittedly, they’ve worked hard to come up with a more repellent ideology than anarcho-globalist capitalism; an impressive feat. The CIA continues its work, alongside the special forces, interfering with other countries’ internal politics in the name of [CLASSIFIED], the intelligence community’s massive [CLASSIFIED] budget and no effective oversight guarantee that it will continue to export and foster terror and political destabilization.

To top it all off, as if in some kind of weird joke, we elected a matinee clown as chief figurehead, and he’s now chafing horribly as he discovers that he’s not the Emperor of America that he thought he was: he’s on Wall Street and the Military/Industrial/Congressional complex’ short leash; all he can do is grab as much cash as he can for himself and his corrupt family, just like the criminals he campaigned against – a red-carpet carpetbagger. #SAD BUFFOON.

Don’t worry about making America great again. It never was. It’s lies written in blood, with a pen-tip made of broken promises.

Happy July 4th!

(Every nation pretty much, is)

National origin stories are an interesting window on how a people sees itself. Their accuracy is almost always questionable, and they change to reflect the concerns of the society they serve.

The Romans were quite unusual in that their origin stories were not straightforward paeons to their own excellence. Rome, so the myth went by the second century AD, was founded by the exiled children of the war god Mars (raised by wolves, of course) and consecrated with an act of fratricide. The first Roman men were refugee thieves and bandits from all over Italy, and their wives were Sabine women abducted by trickery. It is clear that the Romans saw themselves as a violent, conquest-driven mass of people from all corners of the world, who took whatever they could from others and were very prone to civil unrest. Just how most of their neighbours saw them really, and not too far from the truth. The myths disquieted a fair number of proud Roman commentators, who sometimes tried to explain them away with ingenious amendations (“lupa” doesn’t necessarily mean she-wolf, it’s also a slang term for a prostitute!), but in general these myths were accepted as an accurate reflection of who the Romans were.

The American foundation myths don’t seem to reflect any comparable tension or self-examination. They cast the early Americans as simple champions of freedom and self-determination, paragons of virtue bereft of flaws or failings. The genocide of the native peoples is erased. Slavery is passed over unmentioned. The capitalistic, oligarchic tendencies of the colonial elites don’t enter in to the picture at all. For a people who consciously model themselves on Rome, the element of self-criticism inherent in Roman self-perception is markedly lacking. Yes, the Romans had Manifest Destiny too (Vergil’s famous imperium sine fine dedo), and a sense of their uniquely high moral character (Livy’s contention that no other people could have come back from the defeats of Cannae and the Trasimene Lakes and won) and a strong conviction that their current state was a sad reflection of the moral excellence of their ancestors (Livy, passim). But they combined it with a sense that there had always been something a bit off, a bit rotten, about their national character, and an understanding that they tended to disrupt and spoil things wherever they went.

Kim Jong Un got into the spirit this year. So much for Fourth of July fireworks…

polishsalami@#2:

Kim Jong Un got into the spirit this year.

Let’s hope it ends there. But it probably won’t. I don’t understand why the US is so utterly dead set on keeping North Korea isolated; stupid national pride. We should just apologize to them for killing 2 million of them, promise never to do it again, and ask them if they’re willing to start trade and normal relations. We must remember that the situation there is one of our creation.

If it wasn’t, then what excuse would the US have for keeping forces in South Korea?

… John Hancock[‘s] smuggled rum and slaves… George Washington, a land speculator who was one of the largest real estate owners in the colonies … a British citizen typically paid 10 times what a colonial paid… Mansfield had already hammered the nail in the coffin of slavery in May of 1772… alcohol consumption were taxed, but real estate was not; it was mere coincidence that the oligarchs’ long-term wealth was mostly tied up in real estate – within a few years of independence the typical American was paying more taxes than the typical citizen of the British Empire…

Can you recommend a book or three explicating all this in more detail?

(William Hogeland’s The Whiskey Rebellion does a good job on that particular episode, including explicit speculation that Hamilton set it all up on purpose to create a strong central government that could collect taxes and repay the Revolutionary War bonds owed to his [other] political patron, Robert Morris.)

Dunc@#4:

If it wasn’t, then what excuse would the US have for keeping forces in South Korea?

I think the US doesn’t need to bother with excuses anymore. They were always pretty transparent, anyhow. “To prevent Chinese aggression” – like, how the Spratly islands are a threat to Los Angeles.

Pierce R. Butler@#5:

Can you recommend a book or three explicating all this in more detail?

Smuggler Nation by Peter Andreas [amazon] has a lot of interesting stuff about the founding fathers.

Slave Nation by Andrew and Ruth Blumrosen [amazon] makes a stronger case than I do regarding the role of slavery in the founding of the country.

And, of course Howard Zinn’s A People’s History is highly recommended for overall context about the creation of the US.

Jefferson and Hamilton, the rivalry that shaped a nation by Ferling [amazon] also instilled in me a lasting suspicion of both of those characters.

PS – thanks for the suggestion, queued a copy of the Whiskey Rebellion

I’m sure it’ll help make me even more cynical about the founders. It’s sad that the more one learns about them, the worse they appear to be…

Marcus Ranum @ # 7 – Thanks!

Am currently reading my way backwards through US history – gonna be stuck in the Civil War for a while, it looks like, so may not get to yr suggestions muy pronto.

As for the founders, they got put on a very tall pedestal: leads to a high-impact fall.

There seems to be more than one Roman origin story, not sure if this was around, it’s from Virgil I think:

Aeneas, Ilio Achivis prodito ab Antenore Aliisque principibus, deos penates patremque Anchisam umeris gestans et parvulum filium manu trahens, noctu ab urbe excessit. Orta luce Idam petiit. Deinde, navibus fabricatis, magnis cum opibus plurisbusque sociis Troia digressus, longo mari emenso, per divisas terrarum oras in Italiam advenit.

This is my rough and ready translation*

Aeneas, when Ilium (Troy) had been betrayed/handed over to the greeks by Antenor and other leaders, bringing the household gods and his father Anchisam by the shoulder and small son by the hand, left the city by night. He sought the risen (mount) Ida. There/from that place, having fabricated/constructed boats, with great and many works the members/confederates of Troy left, across the long traversed sea, through diverse lands came to the shores of Italy.

*It’s bound to be so wrong, but this is about the level my Latin got to when I was learning from books a decade ago and it’s gone downhill since, so apologies and it gives Carto an opportunity to do his thing!

cartomancer@#1:

It is clear that the Romans saw themselves as a violent, conquest-driven mass of people from all corners of the world, who took whatever they could from others and were very prone to civil unrest. Just how most of their neighbours saw them really, and not too far from the truth. The myths disquieted a fair number of proud Roman commentators, who sometimes tried to explain them away with ingenious amendations (“lupa” doesn’t necessarily mean she-wolf, it’s also a slang term for a prostitute!), but in general these myths were accepted as an accurate reflection of who the Romans were.

That’s one of the things I always liked about ancient Rome: they were pretty “self-actualized” (to use a pop psychology term) – they didn’t BS around about how they were doing things to make the world a better place, or anything like that: they were there for Rome, for Roman reasons, and if you didn’t like that, you’d best not like it quietly, or else. Genghis Khan had a similar clarity about his politics, as did Alexander.

I would say that the transition to national armies, which was pioneered by Bonaparte, also required the militarization of the populace, which also brought in the need to propagandize them silly. I suppose one could also argue that Rome’s population was militarized, at least at first. Did Rome have anything like a “manifest destiny”?

Carto is your man, but Caesar did the genocide thing in Gallia for internal political reasons. The Gauls had sacked Rome centuries before, so were the days Islamic terrorists, and it played well to the populus to conquer them. Something an ambitious politician/general would do to get a nice job and avoid prosecution. I’m not sure it was more than that.

A lot of Romans thought the change from old Rome, a city state with civilian militia, to an empire with standing army was a moral failing and not a good. So it wasn’t Roma, Roma, future yeah! for everybody in my limited knowledge

Marcus Ranum @ # 11: … ancient Rome: … – they didn’t BS around about how they were doing things to make the world a better place …

At least during their later phases, Rome laid on the propaganda pretty thick. Note, e.g., how the raunchy Greek gods got transformed into the noble and high-minded Roman pantheon. I don’t think, however, they tried too hard to bullshit the conquered subjects of the Empire that their enterprise had purposes more elevated than Loot (taxes), though they did attempt to assimilate the local nobles & thugs into joining rather than opposing Imperial gangsterism.

Rome absolutely had a version of manifest destiny. “Civilization” to a Roman was synonymous with Roman material, military, and political culture. Acquisition of territory for the Empire was predicated on the servile nature of non-Roman peoples and their inability to govern themselves in an orderly fashion (the Roman fashion). Even the Greeks were considered this way, as the Romans believed themselves the rightful inheritors of Greek culture and the contemporary descendants of the Classical Greeks to be effete and decadent, unworthy of their own heritage, construed as an idealized Spartan military culture with Alexander’s will-to-power. It was absolutely Rome’s destiny to rule the known world and ultimately it counted as proof of the inferiority and servility of their subject peoples that they had been conquered and enslaved.

Did Rome have a concept of “Manifest Destiny”?

Yes, but as ever it’s more complicated than that. The most famous statement comes from Vergil, Aeneid 1, when Jupiter explains that he has given the Romans “Imperium sine fine” – Empire without limits. Vergil’s poem claims explicitly that it was the will of the gods that Rome would take over the territories it did. But, of course, the will of Jupiter in Roman thought was not really the same thing as the Will of God in Christian thought. Jupiter was a capricious being, and his will wasn’t always synonymous with justice or moral rectitude. The claim that the gods had preordained Rome’s triumphs was not a claim that they were therefore good and right and laudable. The gods had preordained some pretty crappy things.

Vergil was also writing at the time of Augustus, when Roman power over the Mediterranean was already at its height. His claim that Rome was destined to rule the world was a retrospective one, not a call to arms to justify further conquest. Roman historians saw Roman dominance of the Mediterranean as inevitable by the first century BC, but didn’t think it had been that way from the beginning. Livy, taking Polybius as his main source, suggests that the key turning point in Roman history was the defeat of Carthage – whoever won in that conflict would go on to rule the world.

The key difference, I think, is that people in the ancient world saw warfare, violent conflict and conquest as a fact of life. Going out and conquering others was not something that needed much justification – it could enrich you with slaves and plunder, and it would make the people of the conquered territories think twice about trying the same thing on you. For the elites it was a source of prestige, influence and wealth, and for the citizen soldiers it was work and national pride and a chance to improve their lot. We tend to think of the Roman conquests as the projects of consuls and senators, with the poor legionaries going along for the ride, but it wasn’t really like that. The citizens of Athens were very warlike too, and consistently voted for more wars in their democratic assemblies. From the earliest days there was a tradition of raiding neighbouring towns to carry off slaves and cattle, and however urban the Athenians or the Romans got they never really left this drive behind.

Brian English, #9

Yes, that’s the story of Aeneas from Vergil’s Aeneid. It illustrates very well how national origin stories change with the times. Vergil was trying to situate Roman civilization firmly in the stream of Greek civilization – laying claim to a kind of cultural legitimacy in the wider world that it desperately wanted as an Imperial hegemon. The Romans had a very ambivalent relationship with Greek culture – it was foreign and weird on the one hand, but it was rich and deep and respected on the other. They desperately wanted to measure up to the glories of Greek achievement, but also wanted to see the Greeks as decadent, effeminate and immoral by comparison (as CJO notes, above).

Some Romans ran mad after Greek culture, particularly the educated elite (Cicero positively adored anything Greek, and his son Marcus knew that if he wrote back from university in Athens with little Greek aphorisms then his dad was much more likely to send him additional funds). Others were very conservative and shunned it as corrupting (Cato the Elder was appalled when Greek philosophers held high profile public debates in the Roman forum). Having the Roman people descended from Aeneas was a good compromise, as he was Trojan rather than Greek but still a part of the foundational story that underpinned Greek identity. The Trojans tended to be seen as more civic-minded and selfless than the aggressive Greeks in the Roman imagination.

Before the Romans got themselves embedded in the Greek world and its concerns they didn’t think to tell stories like this. Aeneas was tacked on to the beginning of the story – he was cast as the founder of Alba Longa, which was the town where Romulus and Remus were born. The episode with Dido was an obvious attempt to place Rome’s war with Carthage into mythic context – rather than a regular butting of Imperial heads it became a tragic tale of love, duty and feminine irrationality. If you went back to the 3rd or 2nd centuries BC and told some Romans that they were descendents of a Trojan prince they would have laughed at you.

Though “orta luce idam petit” should be “at first light he set off for (Mount) Ida” (ablative absolute there), and “magnis cum opibus” should be “with a great quantity of wealth” (ops, opis – wealth / resources, not opus, operis – work). Not bad after all these years though!

@#10:

That’s one of the things I always liked about ancient Rome: they were pretty “self-actualized” (to use a pop psychology term) – they didn’t BS around about how they were doing things to make the world a better place, or anything like that: they were there for Rome, for Roman reasons, and if you didn’t like that, you’d best not like it quietly, or else.

I certainly don’t like hypocrisy. A state, which talks about freedom, peace, and justice while simultaneously sending their troops to invade other places left and right, killing civilians, torturing “terrorists”, looting natural resources, and generally trying to conquer and control the whole world, is nothing nice. But I still think that states, which openly declare that they want to be jerks (are “self-actualized”), are even worse. When a country openly declares that they want to invade, loot, and commit some genocides, then they commit a hell lot more atrocities compared to hypocritical states like USA. Therefore overall I still prefer hypocritical states who bullshit around about how they are doing things to make the world a better place.

Swoon, my man crush on Carto is still strong.