Is this the right room for an argument?

I’m going to try something here that I consider daunting: as a side effect of this module, I will attempt to offer a refutation of two important paradoxes/arguments that bedevil philosophers and skeptics. Not one, but two! In the interest of Argument Clinic, however, I am willing to fail in the attempt even though it may leave me covered with shame and ripped to pieces by The Commentariat(tm)

In fencing, a destroying parry is one in which the defender’s blade kills the momentum of the attacker’s blade, leaving them in a known position for a riposte.

I don’t know who drew this, but I love it (via google image search) I’ve had that done to me, by the way, and it sounds exactly like “ta-tummmmm” the “ta” is the parry and the “tummmmm” is the sound of losing.

If you’re familiar with the concept of a beat attack, in which the attacker knocks the defender’s blade out of line so they can attack through the opened line, a destroying parry is sort of like a beat parry, if you will. The feeling is a sort of “ta-tummmm” – Musashi calls the technique “To Apply Stickiness”[1][text below] In discussion, the destroying parry is a feeling of cutting at your opponent’s attack while they are still setting it up, and preventing them from pursuing it further, while taking the initiative away from them and leaving you in control of the movement and their position.

In an argument, the destroying parry is delivered as an blocking maneuver on the opposition’s presuppositions or definitions of terms. If you challenge the opposition’s presuppositions immediately as they are rolling out their argument, they’re going to be left in a tough position – they have to either 1) look incredibly weak as they say “wait, let me finish making my point…” or 2) look incredibly weak as they start trying to shore up their definitions on the fly, “no, wait, that’s not what I mean…” Let’s look at two case studies: Zeno’s paradox of movement and St Anselm’s ontological argument.

Zeno’s paradox of movement (in case you don’t know) goes something like this: In order to move from point A to point B you must first go halfway between A and B. But before you can go halfway to B, you must go 1/4 of the way. And before that, you must go 1/8, etc. Eventually, we discover that there are an infinite number of sub-distances that must be covered, and so we can never even begin our voyage because we must first cover an infinity of impossibly small distances. So, the destroying parry to Zeno’s paradox is: “Your definition of movement is wrong. You’re defining movement as requiring subdivision into infinitely small distances, when it’s obvious that I don’t move that way. I cover more than infinitely small distances; in fact I cover an infinity of infinitely small distances every step I take.” In other words: reject the definition from the beginning. Now, your opponent is left with nothing: they can continue to trot out their clever-sounding paradox if they want, but they’re going to have to repair their definition and they probably haven’t thought of a good way to do that.

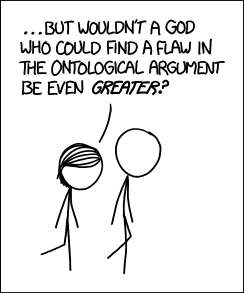

The same destroying parry works on many, many, religious arguments, because – in my experience – a great many religious arguments depend on sneaking things into the definition. Let’s consider St Anselm’s ontological argument, next. It goes thus: god, being defined as greatest and most perfect must exist, because existence is a form of greatness and therefore, the greatest most perfect god must exist. I simplified the ontological argument into a cartoon, there, to make it more obvious what’s going on; some ontological argument junkies like Plantinga add a lot of baroque fluff to the basic argument in order to make it less clear. There’s a specific attack against those techniques, as well, which I will explain after we deconstruct the destroying parry against the simple form of the ontological argument.

“Your definition of god is circular. You’re defining ‘existence’ as an attribute of perfection, you’re just sneaking it in under cover of ‘perfect’ – nice try.” I don’t want to pretend to be a great philosopher; my version is a weaponized reformulation of a much more elegant (and wordy!) take-down by David Hume, who said something to the effect that it’s curious that only divine perfection has ‘exists’ as a presupposition of its definition. We do not presuppose that ‘existence’ is a condition required in a perfect bottle of wine, or a unicorn. One can use imagined perfections in both directions: imagine a perfect afternoon at the beach. By definition, it being only an afternoon, it will end. So it cannot be perfect because a perfect afternoon at the beach would be endless. The destroying parry works just as well against my perfect afternoon at the beach: “your definition is circular and contradictory because it depends on perfection being impossible.”

One of the great things about a destroying parry against a theological argument is that most of the time, theologians are regurgitating very old arguments, indeed (I’m looking at you Alvin!) and often they haven’t thought beyond the card that they’re going to play. When they play their card, you pick it up, tear it to pieces, and say “now what?” They often haven’t got a follow-up. Or in many cases, their follow-up is to grab a shovel and make dirt fly, like William Lane Craig does with his stupid Kalam cosmological argument: it’s been refuted over and over but he just keeps trotting it back out, like a fencer who knows only one cut that you can easily parry over and over until you finally die of boredom.

The destroying parry in argument clinic is a great way to shut down your opponent and leave them thrashing helplessly while you cut their throat. It’s best if you can launch the parry as soon as they start trotting out their argument, though it also serves well as a strong riposte. You can listen with your arms folded then say, “that’s a beautiful case study of a circular argument. Circular arguments are when your argument depends on your definition proving your argument, i.e.: you’re presupposing that motion happens in infinitely small steps in order to argue that motion happens in infinitely small steps. Wow, I’m really impressed by your acumen, Leftenant Obvious.”

In the case of Plantinga’s formulation of the ontological argument, or someone using a technique similar to his, you can use the basic destroying parry and then cut their throat with an (accurate!) accusation of intellectual dishonesty. Jump in quickly and say, “I have to challenge your definition as circular, but do go on…” then stand with your arms folded while they rattle about waving their sword of verbosity, and sink the pin: “… worse, you set up a circular definition then rattled on for 4 pages while hoping I would forget that you tried to slide a circular definition past me. You were hoping that by the time I got through all your verbiage I’d be so bamboozled I wouldn’t be willing to haul you back and point out that you’ve embedded ‘existence’ into your presupposed definition of ‘perfection’ and made an elaborate and dishonest diversion trying to distract me. I thought you were a philosopher but you’re just making debater’s arguments.”

In the case of Plantinga’s formulation of the ontological argument, or someone using a technique similar to his, you can use the basic destroying parry and then cut their throat with an (accurate!) accusation of intellectual dishonesty. Jump in quickly and say, “I have to challenge your definition as circular, but do go on…” then stand with your arms folded while they rattle about waving their sword of verbosity, and sink the pin: “… worse, you set up a circular definition then rattled on for 4 pages while hoping I would forget that you tried to slide a circular definition past me. You were hoping that by the time I got through all your verbiage I’d be so bamboozled I wouldn’t be willing to haul you back and point out that you’ve embedded ‘existence’ into your presupposed definition of ‘perfection’ and made an elaborate and dishonest diversion trying to distract me. I thought you were a philosopher but you’re just making debater’s arguments.”

Plato’s Socrates, probably the all-time champion of Argument Clinic (because Plato could cheat for him!) used this technique all the time: he’d use a destroying parry to get his opponent to define the terms, then obliterate their definition and step back, folding his arms, and say, “but, dear friend, you now leave me more puzzled than I was when we began, for now I truly don’t understand what you mean by <whatever>”

The verbal destroying parry: winning Argument Clinic since 600BC!

Exercise for the reader: what is a good destroying parry for Kalam?

To Apply Stickiness: When the enemy attacks and you also attack with the long sword, you should go in with a sticky feeling and fix your long sword against the enemy’s as you receive his cut. The spirit of stickiness is not hitting very strongly, but hitting so that the long swords do not separate easily. It is best to approach as calmly as possible when hitting the enemy’s long sword with stickiness. The difference between “Stickiness” and “Entanglement” is that stickiness is firm and entanglement is weak. You must appreciate this. – Miyamoto Musashi

Wouldn’t the true destroying argument to Zeno’s paradox be “Some infinite sequences converge”? You cover half the distance in half the time, and the sum of that sequence is the same amount of time as the trivial definition.

sqlrob@#1:

Wouldn’t the true destroying argument to Zeno’s paradox be “Some infinite sequences converge”?

I’d say that’s more of a parry/counterargument – when you engage with the paradox that way, you’re implicitly accepting the initial premise that I can arbitrarily divide your travel into units I decide upon. That’s what the whole argument hinges upon.

The second premise of kalam is “The universe began to exist”, but that’s a presupposition with no evidence.

To sonofrojblake

There’s so many errors to the Kalam, that it’s hard to know where to start. It assumes a beginning, when the evidence is unclear. It assumes that there can be stuff outside of time. It assumes that stuff outside of time can cause a beginning of a time and space like ours (assuming it had a beginning). It assumes that a beginning of timespace must have a cause, but it also assumes that things outside of time don’t need causes – which is a pretty naked “special pleading”.

Finally, even if you grant the entire argument as commonly formulated, the best that it does is get to “some god exists”. It might be a deist god. It might be the god who created the aliens of Rigel 7 in its image. Even if you grant the entire Kalam argument, it gets you absolutely no closer to the Christian god, nor any god that matters. Because I can name a mutually inconsistent god hypothesis for every star in the observable universe, and each such god hypothesis is just as likely on the mere basis of the Kalam argument, therefore we need to apportion the odds equally to each such god hypothesis, which means the Kalam just gets us to 1 over 1 trillion trillion odds that the Christian god exists, which practically might as well equal 0. That’s a really shitty argument if you want to reach that conclusion. In order to reach the conclusion for the Christian god, you need to bring evidence that is specific to the Christian god hypothesis, and the Kalam is not that. The Kalam is simply a non-sequitir.

Playing Zeno: *raises eyebrows* But I agree that you appear to cover an infinity of infinitely small distances. My point is that the appearance must be illusion. You may well claim that it is “obvious” that motion does not work the way described by the paradox — but is that not subtly begging the question?

(I used to think that the fact that there is a smallest unit that space/time is divided into (Planck units) meant that it was not actually physically possible for space/time to be infinitely divided, but I recall Rob Grigjanis arguing that that was not actually the correct conclusion, although I forget the reasoning)

From circles to dates, I find so far that full perfection necessitates existing only in imagination.

Another response to Zeno’s paradox that occurred to me runs something like this: The paradox has, as an implicit assumption, the premise of motionlessness. How about we argue against this? Absolute motionlessness is what is actually impossible: All things, living and nonliving, have some energy, and it is this inherent energy that results in micromotions that can build up to macromotions. The muscles in a turtle’s legs, like in our own, consist of molecules that react to chemicals that are moving at ambient temperature. Even a single proton at 0 Kelvin moves due to zero-point energy. It is not motion that is paradoxical, but rather motionlessness that is the illusion.

Take that, Zeno!

Come to think of it I wonder if something like that can be used against the Kalam argument as well? The cosmological argument is framed as being an answer to something like “why is there something rather than nothing?”, but that implicitly assumes that complete, utter, nothingness is possible. But the theistic/deistic answer cannot be correct, because God is not nothing, and if God never began to exist, then there never was nothingness in the first place. If we are going to posit that something exists that never began to exist, there is no good reason to say that this “something” — whatever it might be — has to be God (let alone a personal God!)

Owlmirror,

Motionless is a conclusion, not a premise.

The motion is displacement* and in both forms (in one, the aspect under consideration is the duration and in the other, the displacement of the motion) of the paradox, that aspect is monotonically decreased towards an infinitesimal.

The actual flawed premise is that an infinitesimal is equivalent to zero.

—

* (s = vt)

sonofrojblake@#3:

The second premise of kalam is “The universe began to exist”, but that’s a presupposition with no evidence.

The first premise can also be destroyed as it’s setting up a circular argument: beginning begs the question of existence.

Pierce R. Butler@#6:

From circles to dates, I find so far that full perfection necessitates existing only in imagination.

You might be able to argue that, which would be tantamount to directly refuting the ontological argument: god cannot exist because one of the attributes of perfection is that it be entirely conceptual!

Owlmirror@#7:

Another response to Zeno’s paradox that occurred to me runs something like this: The paradox has, as an implicit assumption, the premise of motionlessness. How about we argue against this? Absolute motionlessness is what is actually impossible: All things, living and nonliving, have some energy, and it is this inherent energy that results in micromotions that can build up to macromotions.

I agree that there are many other problems with Zeno’s paradox (I think your first role-play as Zeno was a fair attempt, but I’d try to bat it aside based on your perception being flawed)

From a standpoint of argument clinic, I’d observe that engaging with Zeno’s paradox to the point where you’re arguing about macromotion versus theoretical stillness is granting way too much to Zeno; you’re down in the weeds with the paradox and are chipping away at details, while implicitly accepting the whole superstructure. That seems to me to be an unwise overall strategy. Reject early and reject often!

The whole business of modeling arguments as a form of combat strikes me as being deeply problematic. Is Zeno, or any other interlocutor, someone you want to “win” against, or are you trying to understand the conceptual problems the arguments are highlighting? The interlocutor might well be confused. but in many cases — Zeno’s being just one — the confusion is based on ideas that aren’t that easy to refute without modern knowledge of mathematics and/or physics, or without unpacking the hidden assumptions.

Incidentally, I note that the WP article on Zeno’s paradoxes says: “According to Simplicius, Diogenes the Cynic said nothing upon hearing Zeno’s arguments, but stood up and walked, in order to demonstrate the falsity of Zeno’s conclusions.” You’re hardly the first to have a pragmatic rebuttal to a sophisticated argument.