A friend of mine wants to make a Naruto-style ‘kunai’ knife out of damascus. Sounds like a fun project!

I’m a terrible sketcher but I tried to outline a few of the options. I’m still noodling around with ideas. What’s interesting about this process is that I can’t see one option being a lot harder than the others; it’s a question of what you’re good at and where you’re comfortable. For example, i’m great with stock removal – give me a die grinder and an angle grinder and I can carve steel like nobody’s business. But I know people who do the hammer dance so well they’d just pick up a hammer and bang bang bang there’s your shape. Hammering skills also include having enough expertise to be able to assemble a hammering plan in your head – figure where the steel gets hit and when in what sequence.

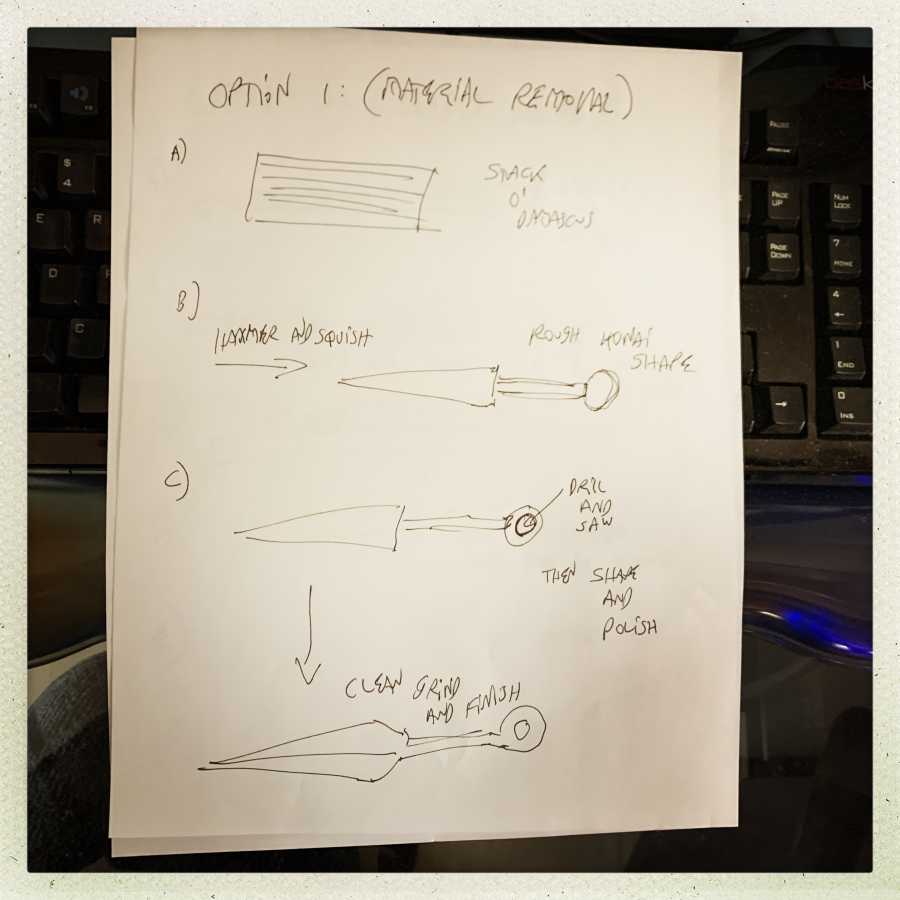

Plan A:

That’s within my comfort zone. I could have that done by tonight. It’s just a matter of burning up a bimetal blade for my scroll saw, and making sure the bar is annealed and soft before I try to shape anything. A pure stock removal approach would be to just take a bar of something flat and drill and cut right out of the flat bar. There’s almost no forging involved beside making the damascus stack.

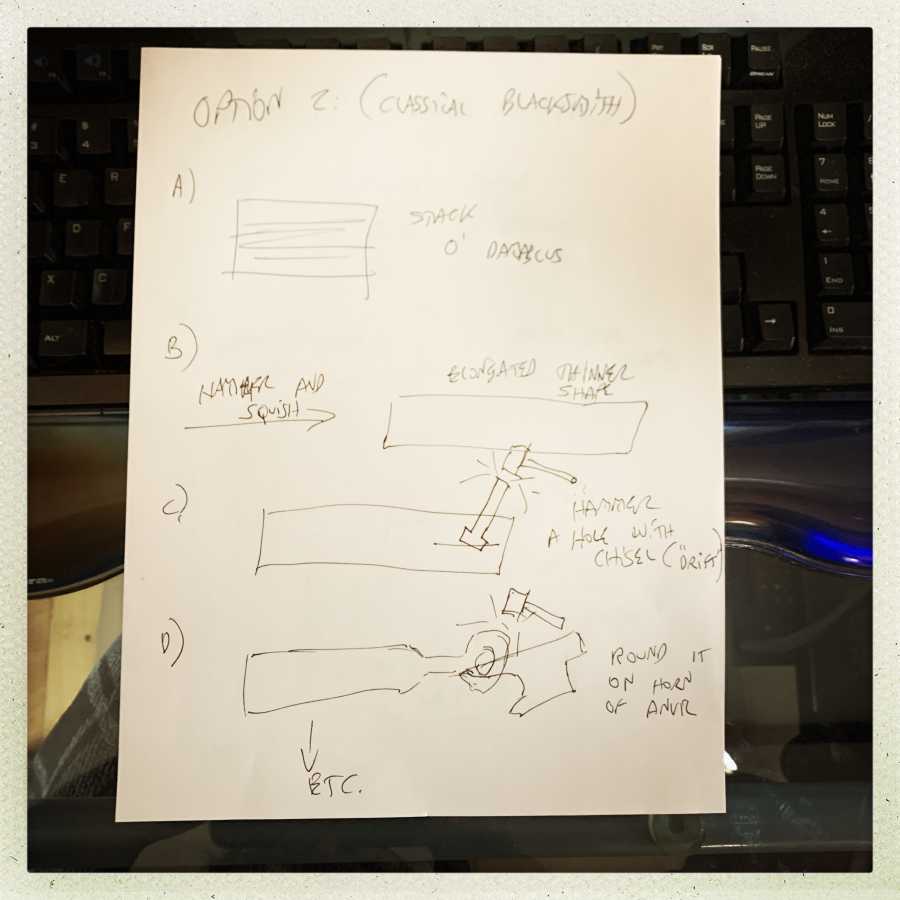

All that removal is a bunch of hard work. Here’s how someone with better hammer-skills would go about it:

Punching a hole in a hot piece of steel with a drift almost always requires an accomplice. Usually, one person holds the steel and positions the chisel/drift and the other person whacks it with the hammer. If you want to see which blacksmiths are friends and trust eachother, if the guy holding the drift is using a gloved hand, they trust the guy with the hammer (or alcohol is involved). If the guy holding the drift is on the other side of the room using long tongs, that’s also an indicator.

The drift approach is preferred for things like hammer and axe-making: you can take a chunk of something hellaciously tough like S7 tool steel and shape it into the exact shape you want where the axe handle will be. Usually axe handle-holes are slightly flared at the top to keep the handle wood locked in. If you do a lot of axes or hammers you make a drift that is shaped the way you want it and you stretch the red hot steel into the position you want it and it’s consistent every time.

If you’re doing a one-off and you’re confident with a hammer, you make the hole with a chisel and then fit it over the anvil’s horn and start stretching the metal around the horn by driving it around and down with lots of little taps. That works great, too. In that case your primary tool is patience and a good eye, because you have to move the metal evenly or the result looks like junk. If you are good with a hammer, you can beat a ring around the horn of an anvil and it’ll come out so precise it looks machined unless you show it to a machinist.

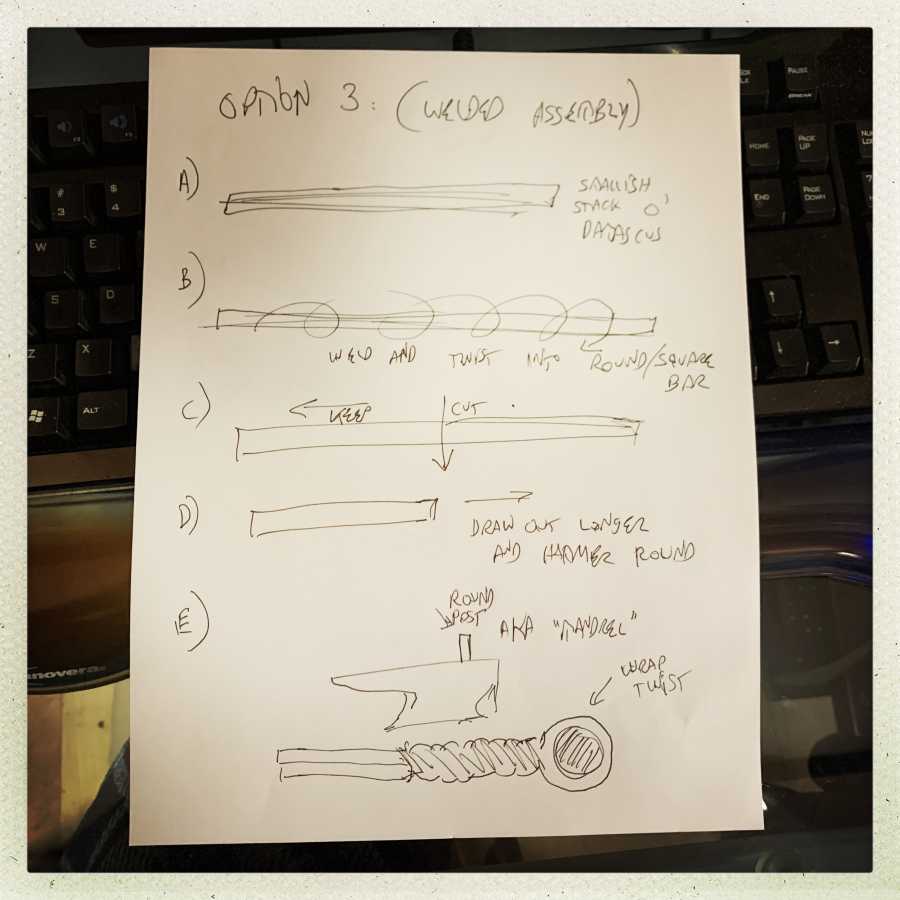

There’s another option, which is to assemble things from pieces and weld them together:

In this case you’re stressing your ability to draw out the twisted bar evenly, then evenly wrap it around the mandrel. That’s not a big deal and one other neat effect is you get a cool twisted handle look. Making the twist bar and drawing it out is easy sleep-walking stuff, as is cutting it and wrapping it. The only concern here is that the welds be good enough to handle the abuse of being twisted again in another direction.

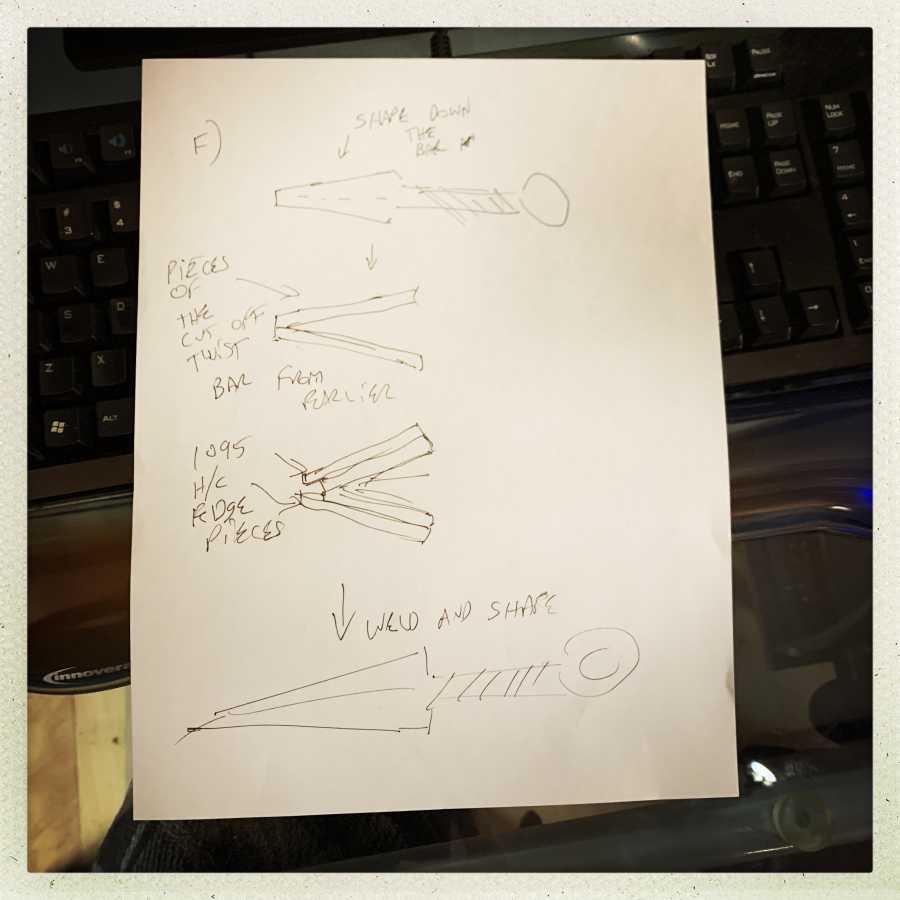

Then, the blade is assembled in another process. This is also nice because you can keep the handle cold and use it as a handle the whole time. So:

Viking swords – the ones with the “serpent in the steel” are made using a similar process of assembly. You might use a core of wrought iron with fancy twists inset between pieces of core, and twisty bars down the sides to form the edge, or whatever. The only “trick” is to keep it all nice and hot and clean when you weld it and to not weld any gaps into a critical place. You can see from my diagram (maybe) that if the welds on the twisted handle weren’t perfect, it wouldn’t matter at all, really – the steel is still plenty strong. On the other hand, if there’s a bad weld in the blade assembly you’ve just wasted the whole thing.

So, this is the pictures I have to think my way to a plan, from. Right now I am leaning toward Option 3, because if it works the result is the most interesting.

Is your friend striving to become the next Hokage?

Ho ho ho kage!

Does your friend also want it balanced for throwing?

Option 3 immediately occurred to me as the coolest option. The ability to use different damascus patterns in the two parts allows for interesting choices

I agree with dangerousbeans. I think #3 is the most interesting. You’re the maker, though, so which would be the most satisfying to make?

Ridana@#3:

Does your friend also want it balanced for throwing?

I need to find that out.

I believe that in Chinese wushu, a knife like this would have a long ribbon through the ring, so it could be whirled, thrown and retrieved, and would act as a drag-tail.

Generally, I’m not a fan of throwing one’s weapons away, but then you would expect anyone who studied kendo to feel that way or they wouldn’t have studied kendo in the first place.

dangerousbeans@#4:

Option 3 immediately occurred to me as the coolest option. The ability to use different damascus patterns in the two parts allows for interesting choices.

I agree. He’s also familiar with Neils Provos’ work on nordic-style blades with inner patterns (e.g.: wolf-tooth). I think if we did it with a twist rod that we cut and used in two places, it’d give a lot of visual self-reference, which would make it look more integral and planned. I’m bungling around with words, there, I’m not sure how else to say that.

In terms of work-factor, it’s not too bad a difference. Obviously, the pure stock removal is pretty hard to screw up, but wow there’d be a lot of grinding. The twist and weld option is a lot of welding and hammering but fairly little in the way of grinding. I know some blade-smiths who’d do option #3 as a matter of course and not think for a second that it was difficult, but they are master blade-smiths and I’m not.

This is the usual teacher’s problem: you want to have an assignment that is hard enough to be interesting and not so hard that it breaks the student’s will to live.

voyager@#5:

You’re the maker, though, so which would be the most satisfying to make?

#3 would be the most interesting to make and would teach the most.