[Thank you all for the thoughtful and insightful comments on the previous posting I did on human supremacy. This is a topic that fascinates me, and I’m still figuring out what I think, which is why I am thinking out loud.]

I’d like to resume my attack on human supremacy, by pursuing a totally different angle. It’s highly relevant, in my opinion, to skepticism in general, gender “issues”, racism, and a whole bunch of other topics, but it also applies to many of the questions human supremacy revolves around, e.g.: creativity, intelligence, motivation, self-awareness, etc.

H J Hornbeck writes [reprobate] about this same issue, which is why I think it’s worth pulling it in to our discussion on AI. Quoting HJ quoting Richard Dawkins:

Everywhere you look, smooth continua are gratuitously carved into discrete categories. Social scientists count how many people lie below “the poverty line”, as though there really were a boundary, instead of a continuum measured in real income. “Pro-life” and pro-choice advocates fret about the moment in embryology when personhood begins, instead of recognising the reality, which is a smooth ascent from zygotehood. An American might be called “black”, even if seven eighths of his ancestors were white. …

If the editor had challenged me to come up with examples where the discontinuous mind really does get it right, I’d have struggled. Tall vs short, fat vs thin, strong vs weak, fast vs slow, old vs young, drunk vs sober, safe vs unsafe, even guilty vs not guilty: these are the ends of continuous if not always bell-shaped distributions.

What Dawkins is talking about, there, is vague concepts. There’s a more formal discussion of vague concepts on [wik] but roughly, the idea of a vague concept is that it’s an issue where, as Dawkins says, there are continua that we wish to carve into discrete categories.

The usual example people use when illustrating a vague concept is “baldness.” So, let’s consider Prince William of England: he’s “balding”. There’s still hair, but there are big areas where there isn’t, and so forth. I think most of us would be comfortable saying “Prince William is balding” but let’s unpack the categorization a bit: is there a specific number of hairs after which you are no longer “balding” you are “bald”? Or, is there a specific hair that, when you lose it, you switch from “a receding hairline” to “balding” or outright “bald”? Do you have to have no hair at all to be bald – not one – or can you be “bald” and actually have 5 hairs? What about 10? Harry’s hair is “thinning” and William’s hair is “balding” but I suspect nobody but the Royal Burrmaster knows the exact hair count, or charts the loss over time.

Vagueness crops up everywhere and that’s why I was a bit uncomfortable dragging it into the discussion (again, I blame HJ) – there are places where things fall on a continuum and we want to chop the continuum up at our convenience in order to use language to talk about whatever the thing is. But, because we want to use language efficiently, we don’t want to spend weeks arguing about what “balding” is and coming up with criteria. We’ve got talking to do! It would be stupid to have to stop and count hairs on royal heads before we could say confidently that William is “balding” but having a definition and criteria is a problem. If we say “50% losses or more and you’re officially balding” we’re still stuck counting hairs. As soon as we say “approximately 50% losses or more” then we’re right back to the problem of “is this guy balding: he’s got maybe 48% hair loss.” I wrote about linguistic nihilism [stderr] back in 2016, describing it as:

We are going to look at a powerful technique for pulling your opponent into a discussion-ending quagmire; it’s the rhetorical equivalent of sneaking off the battlefield under cover of darkness.

Of course, this stuff can be hugely consequential. Consider the “one drop rule” as a response to the question “what is a ‘black person’?” Perhaps someone well-meaning once asked a racist “how can you tell who is ‘black’?” and the “one drop rule” was, actually, the only answer that makes any kind of sense given people’s understanding of population genetics at the time. The problem with vague concepts is categorization, and that’s hugely relevant to many of the things that we do, and how we think about things. I’m going to have to raise the Chomskyite flag here: I do agree with Chomsky’s position that: (roughly)

– Language is the stuff of thought

– How we use language affects our thoughts

– How we think affects our use of language

with one caveat, which is that we cannot possibly talk about thinking without using language – that’s where the linguistic nihilism comes in: I can accuse you of mis-translating your thoughts into the words you utter, because your words were actually ineffable or something like that. I am trying very hard to be fair and intellectually honest here, but this looks to me like a situation ripe for pyrhhonian-style withholding of judgement: we can’t claim to know anything unless we can describe it, and since vague concepts are indescribable, it is hard to make a statement of fact regarding any vague concept.

Let’s try it on AI, now.

When we talk about something being “creative” let’s arm the trap by saying “creativity is a matter of degree; there is a continuum between ‘not creative at all’ and ‘highly creative’” In my previous piece on this topic, I mentioned that I am quite comfortable saying that my dogs were “creative” [and I stand by that!] but perhaps it’s a matter of degree. I am a highly creative person, my dogs were fairly creative (for dogs) and I know some people who aren’t particularly creative. Let’s consider the bottom of the continuum of creativity: a cockroach. If you try to pick it up, it may attempt to run and evade. Is running away a creative process? It had to figure out a new course, direction, and speed. Granted, that’s not very creative, but if you put Napoleon Bonaparte’s mind into the cockroach, he’d hardly have been able to develop a more sophisticated strategy than the roach, because of limits inherent in being a cockroach. On the other hand, Napoleon’s maneuvers at Austerlitz were highly creative (history-makingly so!) so – there’s a continuum of creativity that is subject to basically how much creativity a thing can muster given its nature, the situation it finds itself in, its past, etc. Now, if humans, dogs, cockroaches, and – yes – AIs – exist on a continuum of creativity, I think we have out-flanked the human supremacist position. AI doesn’t have to be some vague concept of “creative” it exists somewhere on the creativity spectrum, and now we can argue about that. Is an AI art generator more or less creative than a dog?

Naturally, the human supremacist might attempt to pull the discussion into a worm-hole, namely, “what is art?” but, the linguistic nihilist skeptic just shrugs and says, “it’s also a continuum.” Is the AI art more or less art? Actually, the classifications completely break down all over the place. What about intelligence?

Yes, what about intelligence? Is an “self-driving” car more or less intelligent than a cockroach? It’s a better driver, and I submit to you that driving is a hard problem and we don’t let human children drive cars until they have a good training-set with lots of conditionals, expertise, and success/failure criteria trained in. I mentioned chess, before, and it used to be one of the high achievements of human intellect held up by human supremacists as an example of how smart humans can be. I remember in the 90s when chess playing AIs started beating human grandmasters, the goal posts moved to “when can AI beat a human Go master?” I was playing a lot of Go at the time, and I remember distinctly that there were positions taken like: “an AI can’t enumerate all the possible moves in a Go game but it’s nearly possible with chess.” etc. AI absolutely clobber humans at some online strategy games that have randomness in the resolution (e.g.: DOTA2) so we can forget about the canard of “an AI exhausts all the options.” I think we’re looking at a continuum representing a vague concept of “intelligence” and the AI keep moving up that continuum.

Is an AI creative? Well, in my previous posting, I tried to explain that the answer must be “yes” because AI creativity can be programmed to work the same way human creativity works. I’ll let the human supremacists struggle to put the word “sometimes” in front of works, but I think that once you put stuff on a continuum, it becomes increasingly difficult to point and say “creativity starts here” and therefore AI fall on the other side of that line. We don’t have to argue about “is it truly creative because it has an inner life?” if a human supremacist wants to assert that an inner life is necessary, they have to argue how important it is to moving the needle up and down the continuum, and how we know that.

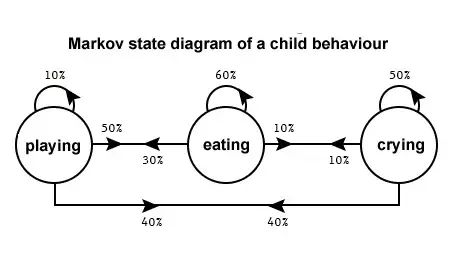

Another comment that often comes up regarding AI creativity is one I tried hard to address in my previous posting. The anti-AI (I won’t call it “human supremacist”) position is something like “all an AI is doing is rolling dice in a big knowledge tree, and regurgitating existing pieces of human art.” First, I tried to explain that that’s what human artists do, too. But more importantly, I think that people who voice that view are confused about how the AIs work. Ok, imagine a Markov Chain analysis of something or other.

[source quora]

When you get into the kind of back-propagation networks that were being built in the 80s (Rumelhart and McClellan’s Parallel Distributed Processing was the text of the day; I still have my dogeared copy) things get really different. So, with back propagation, you simulate a bunch of activity then ask the network to go back and “given all the things that you activated, let’s jiggle the probabilities at the nodes that were activated the soonest, or hardest (depending on algorithm) and see what it triggers, again.” What’s going on is hellaciously complex, and I believe it’s possible that human supremacists mistake our inability to fully comprehend what is going on, with there being something special. That takes us back to the question I was asking earlier, “if we put everything on a continuum, you have to argue that there’s something special that moves the needle one way or another, and how it affects the needle.” If a cockroach’s “run away” algorithm does not produce new strategies, we should not expect an AI to always be brilliantly creative.

I think that’s what’s bothering me about the human supremacist position. It wants to uphold humans as special, while simultaneously situating us on a continuum, or avoiding the continuum altogether. Why should we say “AI are not intelligent” when we can accept that a dog is intelligent, in a doggy sort of way? Or “AI are not intelligent” when they demonstrate emergent strategies much more effective than a cockroach could come up with? The more I think of this, the more I find I am concluding that:

AI are intelligent

AI are creative

and perhaps that’s because a lot of people are not very intelligent or creative, and I don’t think we are being honest if we compare a low intelligence AI with a genius human. It is absolutely incontrovertible that ChatGPT carries on a better conversation than Donald Trump, and he was the president of the United States, once, and may be again. I think that a lot of the barriers we held up have already been jumped over. We’re arguing whether self-driving cars are as good as Nikki Lauda, when we should be looking at whether they’re better than a typical 16 year-old male human. See what I just did? I placed it on a continuum. Because being a good driver is also a vague concept. I know that talking about the Turing Test is passe, but it is for a reason: AIs today are passing the Turing Test constantly. You can no longer look at an article on a website and be sure it was written 100% by a human. In fact, given the way some people write these days, the smashing of the Turing Test is a good thing. But remember, it was human supremacists who were holding up the Turing Test like some kind of shield of specialness.

All that said, I don’t think the AIs are going to get together and wipe out all the humans. Except maybe Nick Bostrom. They’re gonna whack that guy, mark my words.

Well done. I agree with all of your reasoning on AI, creativity, intelligence, and continua. I may relate an anecdote later about my encounter this past summer with a surprisingly creative young cockroach.

That Dawkins quote is ironic given his transphobia

I still think a lot of the problem here is the idea of intelligence as a singe concept. You can’t say something is intelligent, you have to define the task you are measuring the intelligence at. A computer system can be built to do a specific task, such as convince humans it’s intelligent, but that doesn’t mean it has some hypothetical “general intelligence”.

You can see this in people; I’m reasonable at maths, occasionally i go non-verbal. Am i intelligent in some general way? It’s a silly question

I am increasingly convinced that the key to creating actual self-awareness lies in realizing the human self is, itself, a convenient fiction, a simulation, and therefore able to be simulated. Stop thinking of it as ineffable, and get to effing it, piece by piece.

I am also completely unafraid of a human-like artificial general intelligence, or whatever you call it, because the worst things about human beings are the result of “this is the best nature could do” and I’m betting we could do better than that. We’re motivated by instincts of disgust and distrust and pain and shame. There is no reason to imagine those are necessary features of a created self-aware and reasoning being.

So yeah buddy, bring on the AIs. I’m embarrassed by the people quailing and cringing about it.

–

I didn’t have time to comment on the first post on the subject, but this goes for both: Marcus, you are confusing the continuum of stuff-that-brains-do (birds, dogs, humans etc, with varying degrees of complexity) with ehat these «AI» algorithms do, which is interpolating between points in its training data. The quality of their output is impressive, but I would say that this is evidence not of any intelligence or creativity on their part, but rather of the somewhat surprising fact that automating these things (chess, go, translating languages, image recognition, generating text and images) turns out to be not only tractable, but relatively easy.

For the question of creativity, I don’t think you have really shown or seen any evidence of that. Consider how your prompts tend to look like «X with Y in the style of Z». This is perfectly set up to suit the way the algorithm works: interpolating between points in a vector space that encode images. It’s perhaps easy to confuse the encoding method (the «stable diffusion» thing) with a creative process (you compared it to removal of marble), but that is really just the way it encodes the data. What you are grtting out when you ask for X with Y in the style of Z is sample output of the diffusion-gizmo that is a linear combination of the diffusion-gizmos for X, Y and Z.

A real uncontestable example of creativity would be something like the invention of Impressionism; photography obsoletes some of the uses for painting, so thinking «what else can we do with this?» resulted in something genuinely new. Midjourney et al literally can not do something like that, because all they do is interpolate between points in the training data.

Another example you might try is to ask for a slithy tove gimbling in the wabe. A human artist would have a think about what a tove is, what makes it slithy, what the wabe is and what it looks like to gimble in it, and maybe come up with some psychedelic-looking landscape of fantasy plants or animals. Midjourney on the other hand will probably find the prompt in its data labels as labelling depictions the the Jabberwock, and output a version of some human artist’s depiction of the Jabberwock, several of which exist in the training data. Given that there aren’t that many existing Jabberwock-depictions, it’s probably not even that hard to just get it to return the picture in the training data essentially unaltered.

That example doesn’t fit. ‘Personhood’ is a social and legal word, not a biological word, and indicates when an individual is conveyed rights by society.

And you would be hard-pressed to find a society anywhere in human history which conveyed rights from the moment of conception, so that anyone backing such a proposition is certainly not a ‘conservative.’

@4,5

The meat bigot has entered the chat.

dangerousbeans@#2:

You can’t say something is intelligent, you have to define the task you are measuring the intelligence at.

It seems to me that that’s what we’re doing when we put something on a continuum – we’re saying “these things are alike, which is the basis on which we compare them.” I.e.: if I put a human, an ant, and a millipede on a continuum and say “more or fewer legs” then we can argue about where on the continuum various members of the set go. I could also say the continuum is “able to do math” and I think ants and millipedes go way down there on the bottom, and the human goes at the top. I still don’t have a definition of what “able to do math” is. The point of all of this is to try to get at the way humans use language to group things without going through the hard (impossible?) work of defining them non-circularly.

A computer system can be built to do a specific task, such as convince humans it’s intelligent, but that doesn’t mean it has some hypothetical “general intelligence”.

You are subtly tilting the playing field by trying to constrain the computer system to a specific task – i.e.: something that might be easier to demarcate from, uh, general problem-solving. Whatever that is. But if you have a computer system that is pretty good at general problem-solving, how is that not somewhere on a continuum we might call “general intelligence”? Of course I am equating general intelligence with general problem-solving, but that’s the whole problem we have going on, here.

For fun I just asked ChatGPT the building/barometer question, how to calculate the length of the hypotenuse of a triangle given we know the length of the other two sides, and the square root of 3. It answered them all correctly (minus the more exotic suggestions involving the barometer). Was that general problem-solving? If I put that on a continuum between a dog, Neils Bohr, and a 15 year-old American student, I’d say it was a bit better than the 15 year-old. I wouldn’t totally be surprised if an Aussie Shepherd was able to solve the barometer problem, though – those dogs are smart.

To your point, ChatGPT is not a program programmed for a specific task. It’s a language model programmed to interact with humans using language. Historically, humans have considered use of language to be a sign of intelligence. IQ tests (notably bullshit, but…) use language as one of the metrics in the test. I don’t think IQ tests measure intelligence, because I think, as I argued above, that intelligence is a vague concept and all we can do is argue about more or less intelligent than ${whatever} but that is an interesting point, I think.

This is fun, and is less relevant to your comment than it is to Ketil Tveiten’s below. I’ll post it here as a bookmark and will try to address some of those issues later. I’ve got some stuff to do during the day today.

Ketil Tveiten@#5:

Another example you might try is to ask for a slithy tove gimbling in the wabe. A human artist would have a think about what a tove is, what makes it slithy, what the wabe is and what it looks like to gimble in it, and maybe come up with some psychedelic-looking landscape of fantasy plants or animals. Midjourney on the other hand will probably find the prompt in its data labels as labelling depictions the the Jabberwock, and output a version of some human artist’s depiction of the Jabberwock, several of which exist in the training data.

One of your problems is that you don’t appear to understand how AI art generation works. That’s OK but you might want to look at diffusion and GANs – because (as ChatGPT said above) there is no storage of individual data points. If you think about that for a second, it’s pretty obvious: the image generator in stable diffusion uses knowledge-bases trained on billions of images, but is only about 4Gb on the hard drive. That’s not simply compression, and there is no “depiction” existing in the training data. At some point or other, no doubt it was exposed to human artists’ depictions of jabberwocks, but it does not simply go through some mish-mosh of jabberwock related images stored in its knowledge base.

I wonder if that one was influenced by Tove Jansson’s Moomintroll art, because it looks to be in that style. But I am deeply familiar with those books, still, and that is not derivative of anything in them.

That’s more or less jabbersomething

WTF

Looks like some old Dr Who BBC costuming, there.

None of these images, or fragments of them, exist in any directly retrievable form in the knowledge base I was using (Juggernaut XL) because if they did, it would eat all the hard drives.

At least as far as the commentariat here goes, I think the ‘Human Supremacist’ position is something like a strawman. I don’t think I read the entirety of the last thread, but I didn’t see anyone seriously defending the “only humans can be creative”. – Rather I saw a lot of variants of, and better expressions of, my own opinion that this current generation of ‘ai’ products aren’t creative.

These ‘ai’ products exist on a spectrum too – a spectrum that runs from clipart libraries, through these programs, and hopefully off into a more interesting future development. Maybe at some point the software systems we use to generate images from prompts will have enough encoded knowledge to know what they’re actually doing – and wont require extensive human input and iteration in order not to produce disconcerting or purely noise outputs.

You said this:

The anti-AI (I won’t call it “human supremacist”) position is something like “all an AI is doing is rolling dice in a big knowledge tree, and regurgitating existing pieces of human art.” First, I tried to explain that that’s what human artists do, too.

But I’m curious if you would defend this claim. A simple test to see if the Human and the AI are doing the same kind of thing might be to ask them to draw a short, say 6-panel, cartoon where *the same* character does six different things. Good luck with that. People have tried making comic books using AIs, and even with significant effort the AI is barely capable of producing sufficiently similar looking characters from panel to panel, while it takes little human artistic talent do do so.

This is because, unlike the human artist – the AI absolutely is rolling dice along a markov chain. Its a very big and complicated chain with cool outputs and carefully curated features and limits. But it is fundamentally assembling its output out of curated randomness. It is not applying any sort of creative judgement to the output to decide “there, that looks like what I intended to produce”. If a human doesn’t set the number of iterative steps correctly, it produces either specks of noise on a blank image, or eventually just noise full of colour. It has no capacity to decide for itself “this is good, this is what I wanted to make.” Without that capacity, I just don’t think you can call it creative any more than the fact that microsoft word will give you a page full of “pencil” clipart if you type “pencil” into the clipart search bar.

My contention remains that the appearance of creativity is in fact the result of vast amounts of human creative input – from the people who built the tool through to those who had their art (and most importantly, tagging/labelling of art) ingested by the machines, to the prompt-crafter and algorithm tuners who figure out how to extract neat looking output, rather than noise or nonsense, from the random-number generator.

This also applies to your comments about ChatGPT vs Donald Trump’s conversational style. While I’ll agree that ChatGPT can definitely produce more coherent responses than trump, and in this one case might actually be less likely to lie than the human would be – I don’t think this is actually anything you could realistically call ‘conversation’. Nor is the AI engaged in ‘problem solving’ if you ask it to regurgitate the solutions it’s ingested that respond to specific problem-prompts. This is because the AI consumed a lot of quizzes and quora questions and university courses. The fact that it can come up with a mostly-correct answer to a very common problem posed in Math and/or logic courses isn’t exactly surprising. Pre-AI-Hype Google search likely could have done so as well – is google search intelligent?

The problem with ChatGPT as any kind of general-purpose intelligence is that it basically ‘solved’ or sidestepped the quite difficult natural-language-recognition problems in programming by just ignoring them completely. It uses principles quite similar to a spell-check or grammar-check software to produce human-like responses to a human question. But lacking any kind of understanding of the words it is randomly assembling, its output cannot reasonably be trusted. You can say that this is true of humans as well, but humans are generally *capable* of such a thing – whereas ChatGPT is simply not. You could ask it “true answers only” to any question, and this would not give you more true output – where the model consumed garbage and considers garbage, it will output garbage. It is so incapable of truth or plausibility filtering that the AI outputs currently filling up the general web for advertising or political propaganda purposes are going to completely ruin the web as a source for AI training data. Because it cannot meaningfully think about or consider the meanings the data it consumes, the data must be VERY carefully curated by some form of intelligence before the model is allowed to absorb it. I would contend that if there’s creativity in the output, it’s this step that produces most of it.

This computer programmer wonders about your assertion that intelligence exists on some sort of continuum. Are you suggesting that degrees of intelligence are at least weakly ordered?* If so, I doubt the claim.

I suppose I could accept a partial order**; but I doubt that, for something as complicated as intelligence, we could reliably say that one is less than another (except for extreme cases like humans and cockroaches).

Or am I over-analyzing this and you’re not making any such claim?

*An example of what I mean by weak ordering is case-insensitive string comparison. “FOO” and “foo” are distinguishable but are equivalent for the purpose of sorting.

**Like complex numbers any two of which, taken at random, are likely unordered. Note that intelligence, with all its different varieties, is a lot more complicated than just “real part” and “imaginary part”.

Tangentially, the term “human supremacist” sfaik originated in what we now call the animal rights movement, and before that the deep ecology movement, in pressing for less anthropocentric understandings of life on our beleaguered planet.

There may also exist some usages of the phrase in science fiction parables of our species’ tendencies toward imperialism, and maybe even in a robots’ rights story or two somewhere, though most of the genre seems to favor HS ideologies.

I personally suspect nearly all this concern will prove misdirected, what with enviroclimatic disruptions removing the technological foundations necessary for practically all long-term AI scenarios. In the shorter term, we may have some serious problems with humans who use AI (or whatever it gets called next) to control other humans, but the electronics comprise at most a secondary factor in those (admittedly extant/imminent) cases.

Do that help anyone to feel any better?

@7: I’m just saying you guys talk like “AI” was an honest descriptor of this stuff and not a marketing term.

Marcus @9: I do understand how these things work, and there’s no necessary contradiction between the small(ish) size of the program and the apparent amount of stuff it contains. This stuff is fundamentally just linear algebra and PL functions under the hood, once you strip away the fancy tricks (back-propagation, adversarial networks, convolution etc) they do to make the training converge in a reasonable amount of time; the thing that makes it hard to grasp is the enormous number of dimensions you’re doing linear algebra in. The simple fact is that Midjourney et al routinely output their training data if you feed them the right prompt, which is what people mean when they say it “contains the training data”.

Your pictures: it wasn’t clear to me if you asked it for jabberwocks or slithy toves here, that feels relevant to the argument. Regardless, my choice of example of a case where you could easily get back the training data was maybe not great, the Jabberwock seems to be way more popular a subject than I had thought.

Anyway, to cut around all the getting-stuck-in-detail: the way to tell an apparently “intelligent” (whatever that means) system from one that isn’t is to play to its weaknesses and not its strengths. It’s easy to see that a chatbot (be it a simple one like Eliza or a fancy one like ChatGPT) is not intelligent by asking it the right questions and watching it fumble incoherently. ChatGPT can fake a lot of things, but fails miserably at any task that can’t be solved by sufficiently good bullshitting or simply replicating some text in the training data. Having it be the guesser in 20 questions is a good example; it tries a few questions (that are pretty bad ones for the purposes of the game) and then gives up. This is what I was getting at with the impressionism angle and the slithy toves: you can test how “creative” (whatever that means) your Midjourney-or-whatever is by asking for something outside its comfort zone. It is designed to be able to interpolate between things that exist in the training data, but has no facility for things outside of that space. snarkhuntr @10’s example of a six-panel comic sounds like a good thing to try.

Unrelated to the other stuff I’ve been saying: I’m absolutely with you on the continua thing; my Hot Take on any subject is that everything is a continuum, and that absolutely nothing (including this Hot Take) is black and white, but some shade of multidimensional grey.

if the directives of bots in Doom are called AI, how is this new shit not AI? the spectrum again – a doombot is a cockroach, midjourney is like a few neurons in a random octopus part, hypothetical future human-like AI would be more like us in some way, and all can be called AI.

also the six panel comic idea is meaningless. you only propose that because you know it would fail – as it presently exists. but what example will you point to when it breaks that barrier? it still has utility now, if you know how to use it. hell, knowing its weaknesses, as you do, puts you on a path to having that skill. go make some AI art, lol.

You are

so rightSorites.i do agree it’s human instruction and curation that makes useful content out of AI tools (why i’d credit marcus as the artist on his AI art), but the method by which the tools operate, i would argue – as a bachelor of them fine arts – is close enough to human creativity that arguing against that is petty hair-splitting. i am subconsciously remixing millions of inputs, as far as i can tell. sometimes i can remember a specific one, but sometimes i can’t. sometimes those inputs are other people’s art, sometimes my own observation, but in the end that’s the same thing.

Great American Satan:

@15: you do not need to take marketing labels seriously, whether that is the primitive algorithms of a computer game’s automated opponents like in Doom, or a fancy-ass autocomplete bullshit generator like ChatGPT; none of these things are anything like HAL9000 or Daneel Olivaw or a Mind from the Culture. Anyone making an algorithm can call it “artificial intelligence” to sound fancy and cool, but that’s just marketing hype that misdirects from what’s actually going on. A bot in Doom is a flow-chart of if-X-then-Y instructions. Midjourney is (once you strip away the technical details that aren’t conceptually meaningful) a high-dimensional version of a brute-force curve fitting algorithm. None of this is Daneel Olivaw.

@16: You miss the point entirely. An intelligent creative entity would be able to perform the six-panel-comic task effortlessly, but Midjourney et al fail miserably, because they aren’t built to perform that particular task. Asking questions you expect will fail is precisely how you interrogate a system that has fundamental weaknesses. “As presently exists”/Future versions: of course you could refine your curve-fitting algorithm to produce sensible output for a particular problem, but again that misses the point. Recall how early versions of Midjourney would produce Lovecraftian horrors when asked to deliver a picture of a hand with the correct number of fingers; this is a demonstration of what goes on under the hood. The whole point of asking the system questions it isn’t built to answer is to see how it works and how it fails.

Consider AlphaZero, the chess version of this technology. If you presented a human chess master with the game of Shogi, that person would be able to play Shogi at least semi-competently, because they are similar games with a lot of transferable concepts. Now, if you asked AlphaZero to play Shogi, it literally couldn’t do it, because it’s an algorithm designed to play chess and not a computerized intelligence.

@18: you are again playing to the strengths of the tool and not to its weaknesses. Of course Midjourney et al can remix existing art, that’s literally what it is built to do. The difference from what human artists do is that when presented with a request for an image, Midjourney et al perform a linear combination of whatever it interprets the input prompt to refer to, while human artists reconsider the initial request and start the creative process (whatever that is) from scratch. Now, when you are asking for something that can be interpreted as a remix of existing stuff, the Dall-E’s of the world can perform OK, but they have nothing to deliver if you ask for something outside the convex hull of the data points in the training data. Put simply, they can remix, but not generate new things. This is what I tried to illustrate with the impressionism example earlier.

@great american satan, 16

Of course I know that it will fail that task, precisely because I’ve seen the dismal results of people trying to convince the ‘ai’ to generate images of the *same* person doing different things. If someone made different software that behaved differently, I would of course have different responses to that. Perhaps someone will come up with an additional algorithm that can be plopped on top of the GAN to force it to only create faces that match a certain template. How they’ll deal with the fact that the underlying software has no real ability to conceive of terms like “the same person” will also be an interesting exercise in (human) creativity.

I’m not sure that the current families of image-generative ‘ai’ software are capable of, in your words, “break[ing] that barrier”. I think they’re neat technologies and capable of producing – with highly skilled human creative input at virtually every level from conceptual to software tuning – really neat results. Does that make the software ‘intelligent’ or ‘creative’? I don’t know. It probably depends a lot on how you define those contentious terms. At the very least, I have trouble attributing either quality to a simple process that lacks any independant volition. It’s not as if you can just leave Stable Diffusion running and have it decide to spontaneously explore the creative possibilities of remixing Star Wars characters with various animals – or pursue a period of abstract expressionism because it decides that realistic forms are insufficient to express the emotions it’s trying to convey. It’s just not what it’s for.

You could dangle paint cans above a horizontal canvas, poke holes in the bottom and start them swinging and maybe come out with something that looks a lot like certain works by Jackson Pollock – would that make the cans inherently creative? Is a Spirograph creative because of the complexity of its output?

I remember more than a decade ago (possibly two decades), a friend had a little 20-questions gadget that just had a little 14×2 character LCD screen and a pair of buttons marked “yes/no”. This thing was actually really damn good at guessing your 20 questions target, if you didn’t pick something REALLY obscure it would get the right result more often than not and usually in a lot fewer than 20 questions. Is that an example of a smarter ‘AI’ than ChatGPT just because it’s better at one specific task?

As far as calling it ‘AI’, Ketil Tveiten has said exactly what I would have said. It’s just a hype/marketing term. Good for attracting investment money desperate for a place to make an unearned fortune. Their point about the hands is an illustrative one as well – these software systems didn’t get better at hands because they looked at the results of their remixing and decided that they didn’t like the results and wanted to improve, as an artist might do. The models also didn’t produce lovecraftian horrors like Marcus’s weird smushed-eye fairy or weird coral-snake-woman above because they wanted to make something visually disturbing or different. The model no more knows or cares about these outputs than it would the distortion-and-static-filled image they’d generate if you allowed them to iterate a few dozen or hundred times more on the supplied prompts. The models are incapable of understanding what they’re outputting, and I think that this alone disqualifies them from creativity just as the involition of the swinging paintcans or spirograph gears does. It is the humans putting the work in (or the humans whose work has been absorbed into the training models) that do the creativity.

Now, I have to stress this again – that does not mean I believe that a computer ‘ai’ system *could not* be creative. Just that these ones aren’t, and that I don’t know if anyone has any real vision towards making one that is. It is probably possible, but I’m not sure when/how it might be achieved.

ketil – how do you know that you are not a flow chart of fancy algorithms? it sounds to me like your beef with acknowledging AI creativity is that the AI does not understand what it is doing, does not have awareness or agency of its own, but why is either of those things a prerequisite to creativity? depends on how you define creativity, and i’m not agreeing with your terms. or your definition of intelligence. your use of both terms privileges humanity far too much. I think the best way to view our intellectual powers and limitations is within the context of all life. a protozoan is thinking in a binary way using chemical switches. it has a kind of intelligence. so does windows 95. i’m okay with that, and it’s kind of sad to see people freaking out whenever it suggested. “the creative process (whatever that is)” – it’s complicated math, it’s algorithms, it’s chemical and electric switches in meat, and it can – to an extent – be achieved by technology now.

snark – i still haven’t seen an argument made here that convinces me understanding is an important part of creativity. all the elements of creativity, when you break it down, could conceivably be replicated by a machine eventually – aesthetic sense, specific goals in narrative or emotive communication, memory of who a guy is from one panel to the next. what aspect of this would be impossible to eventually program, if anything? and if fully human-like creativity is ultimately possible, how is current AI art *not* at least partway up the path, like a cat is partway between protozoan and human cognition?

snarkhuntr @20: Yes! It is not that an artificial intelligence with creative ability existing on a computer is impossible, it’s that this shit isn’t it!

To be direct, every apparent advance in artificial intelligence is actually a realization that the problem in question turns out to be easy(ish) to solve with existing mathematical methods, applied correctly. Those clowns who thought that “playing chess is the benchmark of intelligence” just did not understand how solvable chess is, given sufficient computational resources. Re-apply that syllogism to any “now this would be a demonstration of artificial intelligence!” you find.

having read the whole comment, it seems the element you would require to consider it creative is understanding of what it’s doing. i can see how that can be important to making “useful” art like illustration, but i don’t personally draw my definition of creativity that restrictively. i can’t, because in using AI art, i’ve seen it generate answers to the input that are equally compelling to anything a human would make, and without understanding. i wouldn’t know wtf to call these things if not creativity.

GAS @21: I don’t know what “intelligence” or “creativity” is, other than that it is obvious that humans possess those traits, but the core of the argument I am making here is that it is plainly obvious when you poke at the technical details here (again, push those systems to their limits) that what the “AI” algorithms do (whether it be LLMs or image generation or whatever) is not it. To reiterate: this is all just fucking linear algebra, however impressive the output looks! The lesson to learn here is that high-dimensional curve-fitting algorithms can solve a surprisingly large class of problems, not that the sand has somehow developed a personality with feelings or whatever.

To take a step back: I’m sure you’ve all had a go with Eliza, or some other simple chatbot, and quickly realized that this is a stupid machine and not an intelligent person. You all can recall the ways in which you came to that realization, and all I am asking you is to apply the same kind of scrutiny to the imagebots. You can easily trip up a chatbot into revealing its nonintelligence, even a fancy one like ChatGPT, and likewise by giving the right prompts you can coerce a stable diffusion bot to admit (implicitly) that it is a moron who cannot think for itself. The difficulty is understanding the ways in which you make the bot admit that, because we as humans are better at asking questions that require hard answers when it comes to language than when it comes to images. The only difference here between Eliza and Midjourney is that understanding the way to make the robot demonstrate it is stupid takes longer and is more diffucult.

GAS @23: the word you are looking for is interpolation. People do it when being creative, but being creative is not the same as doing interpolation. Midjourney et al do interpolation, but they cannot do anything else.

Having read the entire thread (to comment 23), one thing I see which is missed in these discussions is the concept of a skill. By that I mean, the ability to execute a task. We use skills all the time. Many of us are skilled at typing, the words we wish to enter into a comment thread are generated by selecting individual letters on a keyboard. Knowing where our fingers are at any moment, and the relationship of our fingers to the keyboard is a learned skill. Similarly, a skilled auto mechanic can identify the size of a bolt head simply by looking at it. Or a blacksmith knows the temperature of the material by its color. These are all skills which can be leaned, and we all have dozens of them.

Is using a skill creative?

I could argue either way on that, but on the whole I think simply using a skill is not creative. Further, we have ample experience with building tools which replicate the same skills we use. In fact, we have made tools which machine to tolerances greater than what a human can do, and do it faster. What we have created with the modern image-generating (and other) AI programs is to transfer the skill of drawing a unique image similar, but not identical to, previous images.

This is where I think Marcus is coming from in his argument that the AI is creative. In previous machines built to replicate human skills the idea was generally to make the machine replicate the task with greater and greater precision, to avoid randomness in the outcome. The AI image-generators have deliberately allowed randomness to occur, sort of. Whether we call them “Happy Little Accidents” like Bob Ross or not, the result is that we are getting images which are similar to the training data but not identical to any one image in that training data.

And this is where (again) I agree with Great American Satan. An artist, or writer, or metalworker, … , whomever, does learn from exposure to prior art. Even their own prior art. The ability to translate an idea into oils, or words, or steel, is based on experience of what has been done before and what works. And for any specific project being worked on, the creator selects which parts of their experience to include. Even more interestingly, people with the same experiences and backgrounds may well select different parts of their experience to make the selection of what to include. And what is truly amazing is that the same person, doing the same task a second time, may also select different experiences to use within a project.

Marcus is suggesting that now that we have developed a tool which performs that selection, and that selection is different every time we run the same tool with the same inputs, that we may have duplicated (at a very small scale) the way a person performs the same task.

The argument which I think Great American Satan is making is that the current crop of AI image generators have skills which are comparable to pretty good artists. But the AI is still simply a tool. Marcus has developed a skill in using the AI image generating tool, and because he has learned that skill he can now use that tool to be creative.

How creative is that AI. Not much. As a thought experiment, let us imagine an image-generating AI which has been trained on all the artwork until about 1900, and also all the photographs ever taken.

Now, ask the AI to create an image showing the profile and portrait of the same person at the same time. What would happen?

I think there are a lot of ways the current AI with that training set could create an image with those requirements.

But would the AI generate images in the art style known as cubism? I doubt it.

Will a future AI? Maybe. But in order to make that leap, the AI would need to cross the boundaries of its training sets.

@GAS, various

I think we’re close to understanding each other’s points here – if not agreeing. One thing that I’m not quite getting is why you insist on reframing the argument as if I, or Ketil, were arguing that AI creativity is impossible. I don’t think that’s the point I’m trying to make here. You want to assert that true AI/AGI/creative AI is *possible*, I’ll agree that I can’t rule it out. I certainly don’t understand programming, intelligence, the brain or any of the other related topics enough to be able to make a statement like “True Artificial Intelligence is impossible”, which is why I keep repeating that I’m not making that claim.

The specific claim I’m making is that the current crop of ‘AI’ software (and not to forget the training datasets) is *not* creative, and is nothing like any kind of real intelligence. Can it produce surprising and sometimes even genuinely beautiful outputs? Absolutely. Does that make it creative in doing so? Here I disagree. For me to see an activity as being creative, I have to believe that who- (or what-) ever is doing the creativity had some intention in doing the thing, and some goal in doing it. Some mechanism for deciding when it was done creating, and of assessing its work in light of its goals (whether self-directed or externally directed). These AIs do not do this.

I see them as akin to something like being given access to a fully-modelled and textured world in Blender, with rigged-up models and even animations already programmed. You press “render” and suddenly a photorealistic image or short movie is generated. Is Blender creative? After all, you just pushed a button and suddenly art appears – surely creativity is taking place somewhere, but where?

I will further claim that the appearance of ‘creativity’ is really the ‘AI’ systems performing their one unique function: hiding attribution. This is the thing that the corporate world is truly exited about: the prospect of ‘art’ without artists, of movie and TV scripts without writers, of marketable novels without authors, of realizable physical designs without the need for designers. Or at least without artists, writers, authors and designers that they have to credit and pay and (most importantly) negotiate with.

And that’s the true genius of ‘AI’ at the moment. Take a whole crapload of human creative output, remix it through a semi-random process, carefully curate – largely with minimally-compensated third world labour – the inputs and outputs of the system and then claim that it is a unique artistic work owned by [company] and with no identifiable human author. So what if the outputs are sub-par and often distorted or disturbing, they’re FREE! The dream of the capitalist – labour without laborers. Look at all the clearly AI generated pages fouling up google searches. Sure, they’re not ready yet to produce new movie or TV scripts, but a few more years of human creativity added to the models might make them just good enough to produce a not-unwatchable formulaic cop-show or James Patterson novel.

i’d agree that AI tools right now require human guidance to make useful things happen, tho that can be very minimal depending on the use you had in mind.

i disagree on the hiding attribution thing every lefttuber parrots (original thought or are they hiding attribution?). when i drew a moustache guy with slicked back hair for “the vices of dr. carlo” i worked from my own memories of what those concepts look like. computer memory works differently from human memory but it’s still memory. my drawing isn’t an exact replica of a photo of clark gable bc i don’t remember a photo of him perfectly and even if i could, i’d know to alter it. AI doesn’t make a perfect replica bc it’s a denoising algorithm placing pixels where they’d probably be per the prompt and other inputs, which will be invariably somewhat different from the source. same end result as me – a non-copied version of the same concept. am I hiding attribution?

one of these days, assuming we don’t follow our current trajectory from cyberpunk dystopia to mad max wasteland first, my fellow lefties are going to need to understand that creative industries as currently constituted will never be saved by unionization. if people want to make a reasonable living at art, they need to build entirely new systems from the outside, and being luddites about labor-saving tools ain’t gonna help them do that.

the current suggested course of lefties is forcing the moneyed entertainment corpos to a bargaining table, getting more scraps for people within the current system – a system that has been hellishly exploitive for a hundred years, specifically because the glamour of a “dream job” effortlessly undercuts solidarity by suckering in a bottomless pool of scabs. there have been some superficial successes recently, but that’s just perpetuating a status quo so toxic might as well be cyanide.

if you want AI art that isn’t disgusting soulless hackwork, you can do that with effort, and in combination with other tools, and it will still be a a hundred times easier and a million times faster than studying oil painting at ye classical olde money atelier. and if you can make your own artistic vision happen more easily, you don’t need to be a child of wealth or celebrity just for the privilege of a tiny ounce of creative control, where you’ll still just be making garbage for The Mouse.

@GAS, 28

“i disagree on the hiding attribution thing every lefttuber parrots”

I’m really confused by this – what point are you trying to make here? You disagree with some vaguely defined point that is ‘parroted’ by ‘every lefttuber’? Cool, fantastic. I’m happy you’re able to express yourself on this topic, but what has that got to do with anything that anyone in this thread has said? Were people citing ‘every lefttuber’ as some kind of authority? Is it your contention that if many different people come to similar conclusions about a topic that it is somehow suspicious or discreditable for them to do so?

“and being luddites about labor-saving tools ain’t gonna help them do that.”

I’m not clear on where these luddites are to be found. I doubt that anyone working in any modern creative field is a luddite about labour-saving tools, except perhaps for some people who chose to use deliberately archaic tools as an affectation or perhaps (charitably) because they think that it contributes something artistically that is lost with the modern equipment. Most working artists I know are more than happy to use any convenient labour saving tool available to them.

As far as the hiding attribution claim – I think it’s best made out with reference to ChatGPT, which can be convinced to spit out verbatim information from its training sets with the right combination of prompts… sure, it *can* generate ‘new’ text, but when it manages to be convincing, useful and correct for a long period, there’s probably a good chance that it’s quoting a human directly – and without attributing the quote. It’s also built into the software from the ground up – the various preferences and biases of the software’s creators are literally coded into the system, with teams of often quite-poorly-paid third-worlders working tirelessly to make sure the systems don’t do anything that the owners don’t want them to.

“my fellow lefties are going to need to understand that creative industries as currently constituted will never be saved by unionization. ”

This is vastly off topic, but would be a great discussion in itself. I actually think I agree with you completely here, though I do think that unionization has certainly contributed to a lot of people enjoying a much higher quality of life as a creative worker than they otherwise would. But unionization isn’t going to ‘save’ these industries, because the forces of capitalism relentlessly enshittifying every industry in our economy are entrenched and powerful.

the idea AI’s chief innovation is “hiding attribution” is almost verbatim in the latest hbomberguy video and was the subject of videos by left youtubers as well. where did the idea originate and how accurate is it? i was playing with the idea they’re all taking the idea from the same source without attributing it, but i don’t believe that. i do believe it’s a bullshitty meme at this point.

when i speak of luddism i’m not talking about primitivism, just specifically labor reacting badly to technology that could threaten their employment. personally i like to dream of a world where all labor is optional, tho a pipe dream it may be.

i don’t mind disagreeing with a person who has good principles. i’ll be glad to see you around wherever we cross paths in the future.

@GAS

I think I first heard that description on the Trashfuture podcast quite a long time ago – it explains quite a bit about the current excitement around AI in the souless-business-drone community. I’m not a particular fan of hbomberguy, so I was unaware that he had covered the topic as well. I think that “Alleged AIs are, at the moment, mainly just machines for hiding attribution” actually has considerable explanatory power as a hypothesis.

You may feel that it’s a shitty meme – but to me it appears to simply be a true observation of the way that AI is presently being used and the way that many of its boosters are hopeful that it *will* be used in the future. Dismissing an argument without attempting to engage with it, because you feel it is “a shitty meme” is certainly something you’re entitled to do, but it’s hardly convincing rhetorically.

Both AI in the generative sense as well as the idea that “AI” is going to guide a business’s decision-making are – in my view – quite clearly ways to avoid attributing something to its actual authors.

Generative AI remix (more or less) other people’s work and present it fait accompli as a ‘new’ product which can be marketed or sold by whomever is running the model without any worries about compensating the people whose work provided the valuable elements of the thing the GAN spat out.

Probably more nefariously, many people in business and government seem quite exited about being able to outsource certain aspects of their business’s decision-making processes to ‘ai’ or other computerized processes. This allows them to do things like price-rigging between competitors in ways that are not presently legally actionable. “We didn’t *conspire* with our competitors to drive up the rent costs for apartments, we all just happen to use the same algorithm to do our price-setting and the computer determined that the best thing for all of us to do is to continually raise prices even if it requires keeping a certain percentage of our rental stock empty at all times. What would you want us to do? It’s not like we can just ignore what the computer tells us to do!”

Police agencies are all hot under the collar to invest in any technology that claims to be ‘AI’ enabled. These programs offer something that all police agencies desperately want: a way to claim that their own hunches and biases are somehow objective truths that can support warrant applications and maybe even be taken into court as evidence. So companies are happy to either market new AI garbage, or just slap a ‘powered by AI’ label on something they were already doing before AI became the new hype term (looking at you, shotspotter).

Actually, Shotspotter is probably the best example i can think of to prove the point. The way the system actually works is that microphones are planted all around ‘certain areas’ of the city and will attempt to detect and even triangulate gunshots. This is an incredibly subjective and unreliable process, and there have been several cases where the police have pressured the company and it’s obliging technical staff into reclassifying ambiguous or negative results as gunshots in order to support the police’s goals (usually a prosecution). Although the company claims that the system uses proprietary ‘ai-based’ technology to precisely and accurately do this work – they actually rely quite heavily on human operators who have the power to over-rule the ‘ai’ whenever the company finds it convenient to do so.

Other than those workers who belong to one of the competing “We’re building god inside the machine” cults, I think that this is the actual dream of most of the companies attempting to build AI systems at the moment. Find a way to do something illegal, immoral or unpopular and blame it on the computer.

But now we’ve wandered well away from the original topic here…. So I’ll stop ranting.

Ok – trying to get back on topic here.

When I was a kid, I owned a book that consisted of a series of pages each of which depicted a different cartoon/caricature. So you would have a cop, fireman, ballerina, soldier, doctor, a whole bunch of different professions with recognizable uniforms and hair/hat styles.

The gimmick with the book was that the pages were split below the neck and below the waist, and the characters were all positioned in the exact same stance with the dividing lines falling in the same places on each. So you could flip randomly though the book and generate different unexpected combinations. Toddler-me thought it was very clever. “Look! It’s a cop wearing a tutu!”

Is that book ‘doing’ creativity? Because other than the scale of the underlying dataset and the complexity of the mechanisms by which it remixes images, I struggle to see that there is a meaningful difference in the *kind* of thing that generative AI does and the *kind* of thing that the book did. Sure, one is vastly more complicated and interesting – but both are capable of producing surprising combinations and ‘new’ images. I mean, nobody drew a cop-ballerina-cop – I ‘made’ that by flipping.

By contrast, a human illustrator might also be remixing images they’ve seen and remembered, maybe even things they’ve drawn before. But there is a level of intention and choice (or at least illusion of choice) in the human artist’s activities that I simply don’t see in generative AI at this time. The artist selects from whatever options are open to them, and they decide when they have done enough work or that the outcome is what they intended to achieve. The software does not. Much like the flip-book, it lands where it lands – it’s up to humans to interpret the output and decide if they need to give the algorithim another spin to generate a better, more pleasing or funnier result.

On vagueness: this is “fuzzy logic” aka “indeterminate sets”, where true or false goes from binary (1 or 0) to “to some degree” ( from 0.0 through 0.5 to 1.0).

The poverty line is an inflexion point on a continua. Below it a person can not achieve their needs and above it a person has a margin extra to their needs. Its somewhat more precise than the other fuzzy examples.

On categories: it may be useful to recognise that we work from a “flag pole” in the center of a category where the fuzzy logic says 1.0, and don’t tend to think about the edges of our categories.

We recognise a category applies to some degree that triggers a normalisation, assigning 1.0 to the application of the category.

Interestingly we use 1.0 as a trigger for action and we don’t generally have fuzzy actions. (Medical diagnosis leads to treatment actions) As Yoda says “there is do, or do not”.

On creativity: what is it? I use ” creating novel responses, or applying a concept in a novel way”.

A cockroach doesn’t do that. It has built in reactions to stimuli. (You could claim evolution by natural selection produced that configuration of cocroach and so that process is creative)

Does a self driving car do that to any degree? I think yes, it may come across previously unencountered situations and apply a set of existing concepts to determine a course of action which may achieve its goal to some degree. If it works it may form a new concept.

Ketil Tveiten@#19:

fancy-ass autocomplete bullshit generator like ChatGPT; none of these things are anything like HAL9000 or Daneel Olivaw or a Mind from the Culture

Wow, look, those goalposts just broke the sound barrier like a slap drone.