Currently, I am in the process of making a small batch (4) of kiridashi. It’s a pretty strict design and, while it probably looks like it’s easy to just make a single large flat bevel, it’s not.

It’s probably easier to make smaller bevels and it’s definitely easier if they are curved; you don’t have to be as dead still on the grinder. I’m not complaining – I love making blades of any sort, it’s just that it’s a bit more complicated than it probably seems. And I sort of cheat.

The way I cheat is by having my grinder on a foot switch. It tears the motor up if I am constantly switching it on and off, so I usually just have my foot planted on the switch. But, when you get down to fractions of an inch, then it sure is nice to be able to spin the grinder down, position the work-piece where you want it and at the exact angle, then (without having to move your hands!) turn the grinder on. The next level of cheating is to use a jig, and the level beyond that is to use a CNC milling machine to shape the blade to within a thousandth of an inch, and just polish it.

Kiridashi are a good chance to see how consistent your hand is. Also, they’re usually made with the nastiest, hardest steel that the smith can produce – which means that, when it’s quenched and you’re trying to fine-shape the edge down to a perfect nonexistence along a straight line – the stuff is glass hard and the grinder works its magic very slowly.

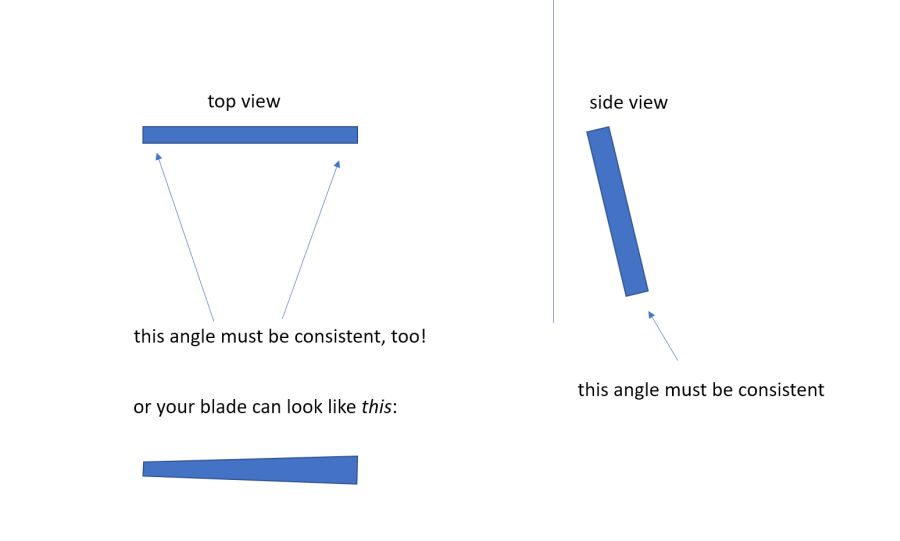

When you’re making kiridashi, the bevel angle and the cutting edge angle both have to be perfect, or it is immediately obvious to everyone.

I’m not complaining. It’s a joy to make things, but sometimes the simplest things are harder than they look.

Why I am dwelling on this, right now, is because I have 4 lovely kiridashi in a variety of sizes, sitting downstairs and I discovered that two of them are a few thousandths off in the top angle, which means they are insanely sharp at the tip and not very sharp at the heel. That sucks because I thought I had them right until I put them on a sharpening stone and the heel resolutely remained dull. There is no sharpening stone that I want to use to remove all the steel from the bevel of a kiridashi, so it’s back to the grinder, which means that I have to re-start the polish and re-etch and re-sharpen. It’s what happens when you’re a bit too tired to be grinding kiridashi, but you do it anyway.

That’s the “gojiradashi” (godzilla kiridashi) which I made as part of a commission. If you look closely, you can see that the edge is slightly curved; that makes it easier to cut with, because the handle is curved, too. “It’s not a mistake” in other words. The steel is motorcycle chain canister damascus, about 1/4″ thick faced onto a piece of 1095 high carbon steel. I don’t know what is in any given batch of motorcycle chain but damn, that stuff is nasty. Even with the blank annealed, drilling that big fat hole in the end was an hour of working my way up through the drill sizes. It does not matter if you’re using a 2,000lb Bridgeport milling machine, or a hand drill, your cutting tool has to survive the heat and torque of scraping layers of steel away from other layers, and the heat that produces.

The angle of the bevel is a bit steeper than I would normally use, but when I made the blade thick, I made the bevel steeper, so it wouldn’t go way back up the handle, where the user’s finger might get “involved” with the edge.

One final point about kiridashi: it’s tempting to make them exotic. I have a vintage Japanese-made one that I bought in the 80s, and it’s made of tamahagane and wrought iron. Tamahagane is the Japanese term for “jewel steel” – it’s the heaviest and most carbon-rich steel that is produced by a given smelting run. Hand-made Japanese tamahagane is now impossibly hard to get, so there are smiths who reproduce the process on their own. I was scheduled to be taking a class at Dragonfly Forge where we were going to melt some iron sands down with charcoal to produce a plug of steel, but Covid intervened and now (apparently) the whole area near Bandon is a mess, with forest fires coming within a couple miles of the Dragonfly shop. I had hoped to score some tamahagane to make myself a proper kiridashi but that may not happen for a while. Another alternative, which I may explore, is to melt down a car brake rotor with some vanadium and charcoal, using a propane/oxygen blown smelter. Fun, but dangerous. It doesn’t get more exotic than that.

The ones I am prepping for my next FTB auction are 1095 with suminigashi facings that are quite thick, so the bevels are gigantic. It seemed like a good idea until the reality of polishing a glacier began to set in.

I love the idea of “gojiradashi” (godzilla kiridashi)” that is just awesome. I have a miniature horse named Godzilla. When born he was only 18″ tall and could walk under the belly of his dam. When he was old enough I sent him to a trainer, who was horrified at his name and just would not say “Godzilla” and instead called him “Goddy Schwartz”, for some reason I cannot fathom. Naturally, Godzilla does not have any idea what his name is, and is convinced that the only reason humans exist is so they can feed him.

I can sympathize with the idea of polishing to a strict angle. Boy does that suck… usually I’m only trying to polish the whole piece, not work it down to a very strict and exact angle. However that is a gorgeous piece and I am sure whoever owns it will be thrilled with how sharp the end is. I generally have a hard time getting the very tip as sharp as I’d like it!

I don’t think using a jig is “cheating” – humans are tool using (and making…) animals, and a jig is just a really specialized tool. I also feel that humans are inherently fallible. Just demanding humans to not make mistakes is an exercise in futility, and you may as well try to bail out the ocean. I think it’s better to accept that humans are prone to mistakes, and try to build systems with that in mind. Off hand, checksums in barcodes and checklists of items used in surgery come to mind…

I vaguely remember reading someplace that knives are a really minor use of steel, and generally not worth making steel specifically for (this may be different now?), so knifemakers tended to find steels made for other industrial purposes, that also worked pretty well for knives. In high-carbon, I think springs were an easy one, especially for larger blades. I can’t remember specifically, but I want to say I learned about this from some ~90s steel, “BG42” or similar, and I think it was “BG” for “bearing and/or gear”, as those were high-wear industrial items that also needed to be fairly tough (not really great to have teeth snapping off a gear, or a bearing getting chipped, I imagine), and it worked pretty well for a knife steel. I imagine a motorcycle chain would have similar requirements, a high wear resistance because of all the moving parts and the amount and speed of moving, as well as some toughness to help resist snapping, maybe?

I’ve also seen a couple youtube vids of smiths doing canister damascus (that’s a pretty damned clever technique!), and I’ve seen them add powdered steel of a decent type, both to help fill in the space, and I imagine to add a known steel to the mix, without interfering with the weird pattern from whatever object they were using for the canister damascus.

Anyways, thanks for posting these, I don’t always comment on them, but I almost always read them, and generally find them interesting.

lochaber@#2:

I’ve also seen a couple youtube vids of smiths doing canister damascus (that’s a pretty damned clever technique!), and I’ve seen them add powdered steel of a decent type, both to help fill in the space, and I imagine to add a known steel to the mix, without interfering with the weird pattern from whatever object they were using for the canister damascus.

The real issue is keeping the billet from falling apart when you first start to hammer on it. The canister is great for that, and having some powdered steel in there also serves to solidify the blows so things can’t go whanging around. Imagine trying to hammer a pile of yellow-hot ball bearings and you can picture what I am talking about. Ow!

The setup I used for the motorcycle chain was a 16ga steel tube with the end crushed down and welded, with as much moto-chain shoved in there as I could get, then I hammered and sifted 1096 powder through the whole thing, crushed the other end down, welded the can shut, and put it in the forge.

Canister welding is a fairly new technique but it’s based on old techniques. The vikings used to put sand on the top of a crucible before they smelted the charge. That way, the sand melted to glass and blocked oxygen getting into the crucible. For the ancient processes, which had long heat-up times, on the order of days, keeping oxygen out was a big deal. It’s less of an issue with an induction furnace and I believe that those are often purged with nitrogen to reduce the chance of the steel catching fire.

I vaguely remember reading someplace that knives are a really minor use of steel, and generally not worth making steel specifically for (this may be different now?), so knifemakers tended to find steels made for other industrial purposes, that also worked pretty well for knives.

You are correct. Many industrial applications include recommendations for quenching, etc, that are based on “you are making a drive-shaft for a 2-story high generator” – a knife is not even a rounding error.

There are some knifemakers and suppliers who have gone into business making their own crucible steels (e.g.: AEB-L) specifically for knives. They’re great steels but they’re really expensive.

I admit I have daydreamed often of resurrecting a form of the puddle iron process to make some wrought iron in largeish blocks. I imagine that there are smiths who would sell their souls for one of those (picture a cast-wrought-iron hammer head or axe-head cast with a groove in the edge to accept a piece of modern high carbon steel) I think most of the people that are doing backyard smelting are aiming for wootz steel or something even more rare and special than lowly wrought iron.

I will further note that I am perfectly set up here to do backyard smelting. My shed is on a giant pad of strip mine tailings – easy to dig into, non-flammable, and dense. It would be easy easy easy for me to run a buried pipe from where my propane tank will be, over to a smelter (buried for safety) and get one of the locals to drag some of the foundation stones from my fallen barn to make a shield wall around the whole area. Like I said: perfect. I even have a 36″ section of 3/8″ thick steel pipe 16″ across, just sitting in my components room. And – best of all – Harbison Walker, the company that makes most of the refractory cements everyone uses – is just up the road in Pittsburgh; I won’t have to pay to ship 50lb sacks of Castolite around. The question for me is if I will live long enough, not when.

I learned about this from some ~90s steel, “BG42” or similar, and I think it was “BG” for “bearing and/or gear”, as those were high-wear industrial items that also needed to be fairly tough (not really great to have teeth snapping off a gear, or a bearing getting chipped, I imagine), and it worked pretty well for a knife steel. I imagine a motorcycle chain would have similar requirements, a high wear resistance because of all the moving parts and the amount and speed of moving, as well as some toughness to help resist snapping, maybe?

Vanadium and Molybdenum, usually. And, of course, lots of carbon to stick it all together.

Chromium gives you “stainless” which has a whole bunch of different things that come along with it (including “nobody in their right mind wants to smelt a crucible-load of anything containing a lot of chromium.”)

kestrel@#1:

When he was old enough I sent him to a trainer, who was horrified at his name and just would not say “Godzilla”

Awwww, that’s too bad! I used to know a fat lazy old horse named “Deathwing” which he completely failed to live up to.

And I’d never try to get on a horse named “fluffy” because I’d be afraid its person had a sense of humor like mine and called any horse that regularly mashed its payload something cute like that.

Irrelevant to anything but this comment: one thing I hate is computer games where you can’t name your horse. Damn, that’s frustrating. I just played through Ghost of Tsushima and was horrified that I was stuck calling my black horse “shadow” (“kage”) instead of “ce qui péte” (that which farts) (the structure lifted from Alfred Jarry, whose bicycle was called “ce qui roule” (that which rolls)) In Red Dead Redemption, a big game last year, the designers even worked on giving the horses various genitalia but not names. So, you could have a well-hung horse but not call him “pepin le bref” (little Peter) (son of Charles Martel and the founder of the Carolingian dynasty) Gah! It’s stupid! For that matter, it took the idiots who coded Elite: Dangerous two years to add ship names to the game.

@lochaber

I’m not sure, but i think 1095 might be somewhat close to an actual blade steel. from memory it’s close to 19th century sword steels? although that’s getting back before there were standard steel blends?

The ones i use a lot are definitely designed for other things; 52100 is a bearing steel and W2 i think was a machine tool bit steel

motorcycle chain is probably some obnoxiously wear resistant mild-steel. it rusts, so can’t have too much chromium in it. you also don’t want them too brittle, so can’t have too much carbon, although the alloying elements would form carbides and reduce the amount of martensite that forms. and as Marcus said molybdenum to help through hardening.

any advice on the overall shape/design of kiridashi? other than something that feels nice in the hand. I’m trying to forge some as practice