There’s an old joke I heard from one of my psychology professors at Johns Hopkins: “A psychologist is studying a frog. He puts it on a table near a yard-stick and says ‘JUMP!’ and the frog jumps a foot. The psychologist notes this down in his lab book and cuts one of the frog’s legs off, then puts it back in its starting position and says ‘JUMP!’. The frog jumps – not as well – 8 inches. The psychologist notes this down and removes another leg. The frog manages to jump 4 inches. With only one leg remaining, the frog is ordered to JUMP! and it manages to sort of shift its weight, painfully. The psychologist records 1/4 inch. When the psychologist removes the frog’s remaining leg, the frog just sits there, and the psychologist writes in his lab book: frog with legs removed loses its hearing.”

It’s a bad joke, but it touches on a fundamental problem of science: sometimes we can confuse cause and effect. In psychology, there was a movement (normally most associated with Pavlov and B.F. Skinner) called “behaviorism” – its tenet being that we should not speculate about inner states of a creature and we should only measure its behavior. We don’t say “the dog drools when it hears the bell, because it is anticipating food.” We say, “the bell rings and the dog drools; there appears to be a connection.”

a “skinner box” – rats can be operantly conditioned using electric shock and food reward

As some of you may know, I’m pretty skeptical of a great deal of psychology, especially the vintage stuff. Most of what I learned about in school seemed to be pointless, if not outright cruel, and worse: wasteful. I remember asking my professor “what was the point of the Stanford Prison Experiment?” and he waffled a bit about what Zimbardo might have expected to learn from it, but really it just sounded like Zimbardo was doing “experiments” for the sake of his own curiosity. I scare-quoted “experiments” because I don’t accept that Zimbardo was actually doing an experiment, at all; to me an experiment has to have a pre-determined measurement criterion that will serve to confirm or deny a hypothesis. I don’t think Zimbardo was engaging in scientific research, at all. I’ve always been a bit horrified by the way my psychology textbooks (this was back in the early 80s) even mentioned such pointless studies – at the same time as they protested the psychology is a science. I’d expect a scientist to only mention Zimbardo as an embarrassing mill-stone, not as a mile-stone in the field. So, I thought that Skinner and the behaviorists were a breath of fresh air: you measure what you measure and you don’t speculate – if the measurement shows something, then there’s no need to speculate.

The problem with behaviorism is that psychology (at that time) really wanted to generalize across species. To me, this was upsettingly pseudo-scientific: an experiment performed on rats does not in any way, shape, or form, allow us to generalize human behavior. An experiment performed on college undergraduates does not allow us to generalize human behavior, either, unless we are able to somehow extract the cultural influences that come along with being a college undergraduate. But, if you look back to the annals of popular psychology from the 70s, there was a great deal of – let’s call it “generalization by implication” – you know: if you put rats in over-densely populated situations, they kill and eat eachother more often; therefore we should worry about cannibalism in cities – that’s the implication. If we put a rat in a Skinner box, we can conclude that: rats are capable of being taught using operant conditioning. Anything else? Not really. We can hypothesize that dogs might be taught using operant conditioning, but to be certain, we ought to try it and see. There’s a reality there, and we can measure it – but what’s hard is to generalize it across species, or to assume that there’s a certain mechanism being exhibited.

That’s where it gets tricky: can we assume the mechanism? If we say that a set of behaviors exhibited by rats, dogs, and chickens in Skinner boxes comprise “operant conditioning” can we claim that the mechanism is “learning” in the human sense? The rat has “learned” how to get cookies by working the lever, but Skinner boxes are obviously not how humans learn. If I take a college undergraduate and offer them $25 or an electric shock to run my test, are they operantly conditioned? It appears to be a different behavior; for one thing, the criteria we use to measure (drooling or pressing a lever) are different. Therefore, obviously, the behavior is different. The frog may have actually gone deaf when its legs were cut off, but unless we have a reliable way of asking the frog, we’ve got nothing.

So, imagine my surprise when I was listening to an episode of The Infinite Monkey Cage podcast [imc] about numbers. At around 5:00 in, one of the panelists asserts that the earliest words in language are counting words. Then he goes on to mention a study that indicates that babies have very early capability for basic numbery-stuff or county behaviors. I deliberately fudged the language there to make it more waffly because the panelist’s explanation appeared to claim confidently that babies can do basic counting because of an experimental result. Unfortunately, I could immediately see a flaw in the experiment as described so I looked around a bit to see if there was a better explanation of the experiment. There’s no need to dig further into the panelist’s beliefs or evidence-based convictions, though I’ll observe that he seems to be engaging in exactly the kind of “interpreting the results a bit too far” that keeps getting psychology in trouble.

Here’s a better explanation of the experiment: [scimag] Let’s look at it a bit and then I’ll explain the hole in the experiment.

If a 6-month-old can distinguish between 20 dots and 10 dots, she’s more likely to be a good at math in preschool. That’s the conclusion of a new study, which finds that part of our proficiency at addition and subtraction may simply be something we’re born with.

Researchers have long wondered where our math skills come from. Are they innate, or should we credit studying and good teachers—or some combination of the two? “Math ability is a very complex concept, and there are a lot of actors that play into it,” says Ariel Starr, a graduate student in psychology and neuroscience at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

One of those actors appears to be the approximate number system, or the intuitive capacity to discern between groups of objects of varying magnitudes. We share this talent with numerous other animals, including rats, monkeys, birds, and fish. Some of those animals, for example, can match the number of sounds they hear to the number of objects they see, while others can watch handlers place different numbers of food items into buckets, and then choose the bucket with the most food. For ancient humans, this skill would have been an asset, Starr explains, by helping a group of humans determine if predators outnumbered them, for example.

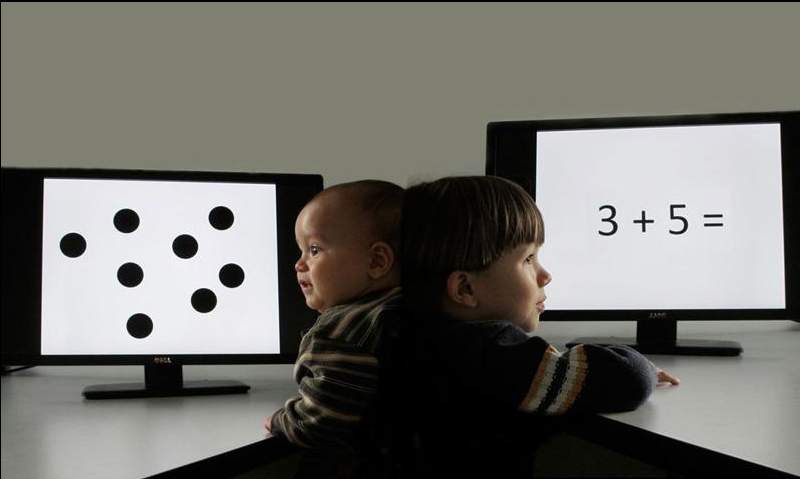

The experimental layout is this: we take a 6-month-old and show them two screens. On one screen is ten dots. On the other screen are a changing number of dots. By watching where the child’s eyes go – which screen they are looking at – the researchers infer that the child is paying more attention to whichever collection of dots is largest. Therefore: 6-month-olds have an ability to discern “larger number of dots” which implies some basic counting ability, which implies some inherent mathematical ability.

Researchers suspect that this intuitive number sense may play into humanity’s unique ability to use symbols to do math. While both a monkey and a human can look at photos of 20 and 30 dots and then choose a photo of 50 dots to represent that total value, only a human can add the symbolic Arabic numerals for 20 and 30 together to get 50.

See where it’s going off the rails, already? Because humans can be taught to do math that helps, uhmmmm…. No, actually it doesn’t help show that their results are significant. Basically, this is like saying “because dogs can drool, they have an innate ability to use language, since drooling can be a form of communication.”

Note that I am not saying anything about whether I think dogs can communicate (I think they rather obviously can, and if you’ve lived with a dog, you will almost certainly agree) or whether babies can count (I think they quickly come to understand ‘bigger’ and ‘more’ or ‘less’) but if we say that babies’ ability to discern “bigger/smaller” “more/less” then I don’t see how that’s evidence that infants can do counting-like stuff. It’s evidence that infants’ eyes function and brains quickly learn certain things about the world around them.

Children who performed in the top 50% of the math achievement test had a significantly higher intuitive number sense in infancy than those who performed in the bottom 50%, the authors found. This relationship held true even when the researchers controlled for general intelligence.

[source]

I’m not saying that none of the experiment’s results are true. I doubt, however, that they have any basis for being so confident that they are measuring what they think they are measuring.

The mechanism of science is that we theorize a cause/effect relationship and try to narrow it down by constructing experiments that confirm or deny the cause/effect relationship by manipulating it. A theory that has predictive power is one where the theory allows us to predict how the experiment will come out, based on the theory. That means that if someone can throw out an alternate theory that has the same predictive power and matches your experimental results: you’ve got a problem. Now, you can no longer claim that your theory is true because you have two theories that may be true – you need to devise an experiment that lets you more finely divide cause/effect to determine which theory is right (or more usually, eliminate the one that’s wrong).

Based on the above, let me show you how to explode this experiment: let’s hypothesize that animals that forage, predate, or are subject to predation, have a built-in function that processes the input from their eyes and detects changes in a scene. For example, suppose you are looking at a field and you see no deer. You divert your attention to check your txt messages on your cellphone and you look up at the field again and immediately notice that there are deer! Yummy deer! Our predator/prey “scene visual change detection engine” allows us to rapidly detect change from one scene to another and it wakes up other bits of our brain to process the changes. Put differently: change is interesting. There, now, that’s just some bullshit that I made up but I think it’s plausible enough that I could use the same experiment to argue that my “scene visual change detection engine” exists in babies. And dogs. And rats. And octopi, if I could figure out a reliable way to see which bunch of dots an octopus was interested in. I can even argue that having a good “scene visual change detection engine” is a component of some aspect of IQ and we should expect that babies who scored better at detecting changes in scenery (more change means more interesting) might turn out to be better at math, someday, if they have parents who can afford to co-sign their student loans.

I’m not outright rubbishing this experiment, but it seems to me that we should be a lot more skeptical of some of the results that get promoted into the popular zeitgeist. Normally, when I take a poke at psychology, someone comes along and says “but that’s pop psychology, real psychology does not depend on old broken concepts like IQ” – except they do. That’s the problem, when your science has built itself on foundations of sketchy results. You can do the best work you can, and the results are still sketchy. As soon as someone in an experiment says anything about factoring out general intelligence, they’ve left themselves wide open for a skeptical challenge rejecting their entire premise.

The bad joke about the psychologist and the frog actually cuts to the core of how we practice the method of science. We use theory to design experiments that allow us to vary cause/effect so we can confirm/disprove the theory. The reason the story about the frog is not funny is because the psychologist in the joke has just as much reason to conclude that the frog has gone deaf, than that legs are important to jumping behavior – unless, that is, the experiment also somehow controls for the relevance of legs to jumping, or has some other way of testing the frog’s hearing.

[source]

Also, the dogs I’ve known (I tend to favor the smarter breeds) (whatever “smart” means) would opt out of the experiment. My dogs, Miles and Jake, had never experienced food-stress and, while they knew what hunger was, they would have ignored the experiment entirely and focused on trying to escape the harness or terrify the experimenter into letting them go. The whole Pavlov experiment seems bogus to me. Other readers with experience with dogs care to support or contradict my opinion?

I will not further belabor the fact that Pavlov’s results are part of the core of psychology’s epistemology: operant conditioning is considered to be a model for how learning takes place. If Pavlov’s experiments are bullshit (as I suspect they are) then we must engage skeptically with extensions of the operant conditioning model of learning; it’s probably bullshit, too. Suddenly we’re in quicksand.

“a tool for measuring individuals against themselves as a baseline and not comparing between individuals” – let’s say that infant mortality in poor children is higher than the rest of the population. Let’s say that some percentage of the babies measured in the study grew up poor and – died. So, now you have social factors skewing the results: babies with more affluent parents might score better simply as a consequence of surviving.

What if an “IQ test” is actually a “paying attention test”? Or a “willing to engage in dull tasks test”? I haven’t even got an IQ anymore because I can’t be arsed to take a test.

We also should be skeptical of any experiment involving babies. Testing them for cognitive tasks is going to be hugely influenced by whether the tyke has been sleeping comfortably, has gas, or is hungry. They’re babies and anyone who spends time around a baby is going to tell you that babies are pretty variable all on their own and they’re not going to be able to tell you why. Did the experimenters normalize the baby set-up to make sure all the babies had clean diapers, a certain amount of sleep, and their mother was in the room? A baby that’s got gas is probably going to behave very differently on the test from one that doesn’t. (See above comment regarding infant variability in IQ tests) Like with Pavlov’s dogs, we cannot ask the dog; perhaps the dog would just say “I’m a mastiff, we drool, stupid.”

“children who performed in the top 50%” – top 50%? That’s making my p-hacking alarms go off. “We measured an almost immeasurably small difference compared to a coin-toss.”

“what was the point of the Stanford Prison Experiment?” – Zimbardo was originally trying to see if he could experimentally determine that there’s something about Germans that makes them more obedient to authority and nobody was stupid enough to fund that. So he managed to secure funding (?where?) and ran the experiment to determine that – what? – people tend to submit to authority. Yes, they do, that’s what authority means.

How do we know that the difference is caused by genetics? I can think of alternative explanations, for example, some parents spend a lot of time teaching, interacting, playing, and talking with their newborn babies; others are single parents with full time jobs and spend much less time interacting with their children. Wouldn’t this influence a child’s mental development?

Looking at where a child’s eyes go prove nothing. If you showed me two drawings—one of them very simple with very few objects, the other detailed and with lots of various shapes—I would spend a longer time looking at the more complex drawing. Why? Because a more detailed image means that there’s more to look at. How do you even conclude that babies perceive “more dots” as anything number-related? How is this supposed to prove anything about mathematics? Maybe it’s just that a more detailed image means that there’s more to look at?

How do we know what exactly the baby discerns? How do we know that they actually discern something? Maybe they are just staring at an image having no clue what it is that they are looking at? How do we know that a baby discerns a “larger number of dots”? And how is this supposed to imply a counting ability?

What’s so hard to believe about a drop counter? (I’m pretty sure the tech existed for it back then, it’s a pretty simple device) The dogs were surgically implanted with cannulas to collect the saliva. They weren’t just holding a bucket under their mouth. And dogs can be trained to tolerate the harness (knowing Pavlov’s other work, he probably tortured them until they just gave up).

Is there something missing from that sentence? Or are you trying to confuse me again. ; )

The thing I don’t understand about the counting babies is, on what basis do the researchers infer that the baby is paying more attention to whichever collection of dots is largest? That is, if all babies always look at the larger group, then how do some babies “do better” at the counting test (i.e., showed a higher intuitive number sense) than others? If babies don’t always look at the larger group, then how do they know larger groups are inherently more interesting to babies, or that they’re looking at the group they think is larger? Maybe they just felt like looking at smaller groups for a change. To me that’s the fatal assumption in this study.

I don’t think any discussion of human numerical ability can be complete without mentioning the Piraha, a people whose language lacks words for numbers,

Here’s a popular summary: What Happens When a Language Has No Numbers?

There are a lot of hits if you search Google Scholar for “[author:everett piraha]”. The one that looks most relevant is: Number as a cognitive technology: Evidence from Pirahã language and cognition

Owlmirror@#3:

I don’t think any discussion of human numerical ability can be complete without mentioning the Piraha, a people whose language lacks words for numbers,

Conclusion: they aren’t human?

I’d never heard of them, so thank you for that. How fascinating!

Ieva Skrebele@#1:

How do we know what exactly the baby discerns? How do we know that they actually discern something? Maybe they are just staring at an image having no clue what it is that they are looking at? How do we know that a baby discerns a “larger number of dots”? And how is this supposed to imply a counting ability?

I also didn’t see anything about whether the baby’s mother was in the room or not. How did they control for the baby looking at/for mom as in “get me outta here!”

They appear to have had a researcher watch where the baby was looking and score based on that. No margin for experimenter error, there!

Wow. That is egregiously unjustified. At best, it’s just a wild guess. I’d assume that’s par for the course in evo-psych though.

While I’m suspicious of a lot of psych, I have outright disdain by reflex whenever I see an evo-psych claim being made.

If you have a group of 10 dots, and a group of 20 dots, and a baby randomly stares at one dot, the odds are two to one that the baby will be staring in the general direction of the larger group. This does not mean the baby can count.

I’m not fond of preferential looking as a measure, but since I did recently publish a study using just that measurement, I feel compelled to defend the experiment, given that you’re not even reading the original research article. (Which is not to say I don’t disagree that most psychologists, especially the ones that enjoy conversing with the general public, as opposed to those that do not, tend to state things way too confidently).

But two brief points. One is that when changing the numbers of dots on the screens, they were almost certainly using masking that very effectively masks subtle, even no so subtle, changes in an image (see change blindness). And secondly, I’d be surprised if they weren’t working off of baseline controls demonstrating base rate preferences of, for example, more dots, but also helps account for problems like left/right bias in looking at the screens.

Now maybe those aren’t true, especially if it was published by the NAoS support instead of through regular peer review.

The Onion: Biologists Announce They’re All Done With Rodents

You seem to put a lot of weight behind the word “generalize.” We’re animals. There are things animals do, which can be studied. Other animals are obviously not the very same thing as humans (not to mention that individuals themselves aren’t identical), but there may nonetheless be a huge number of significant patterns which could help us understand the world a little better. So let’s see what we find and “generalize.”

That’s basically all the thought process needs to be like as far as I’m concerned, and it seems perfectly reasonable (also maybe a bit boring, like a lot of reasonable shit). The more nonsense you add to it yourself, the more you’re strawmanning. Or just failing to consider/understand the strongest case that can be made for the thing you’re opposing.

You don’t seem to have an issue assuming that there is a mechanism. (You start by simply asserting that there is a reality about it that one can examine, which I don’t think is problematic.) Instead, what you want to contest, apparently, is which specific mechanism it was that some specific people happened to propose, as well as the logical or empirical justification for that … or at least this is how it goes when that’s done by a group of scientists you don’t trust very much (for whatever reason).

This is very confusing. What do you think would constitute an ability to do counting-like stuff, if it isn’t discerning something like bigger/smaller or more/less? Those English words are about magnitudes, no? I don’t know how counting-like stuff could happen without the use of some such set of concepts about exactly that type of relation. What you propose wouldn’t show infants know abstract algebra, but it would be evidence that they have some core abilities necessary for counting (at least so far as I understand what is meant by “counting,” as I think I do).

First, you were the one to propose that we could say (at least for the sake of argument) that babies can discern bigger/smaller or more/less. This is what I said would be evidence of counting. But I can only guess that you’re shifting back to the particular methods of that study you were criticizing, instead of your own generic proposal (with no details about its methodology given) that you claimed wouldn’t constitute evidence.

I mean, yeah, in the study, the people presumably measure their gaze somehow, maybe it has more to do with certain things grabbing their attention or what have you, not a process like counting … I get that. But none of that’s required in your statement above. Wherever that bit was going may have just been lost in the editing stage (very understandable) but in any case, it’s hard to grok how you think this argument is supposed to go (or if it’s actually the one you wanted to make).

If discerning (whatever exactly that means) between bigger/smaller or more/less is supposed to be evidence that their eyes function and that their brains quickly learn certain things about the world around them, then you should have mentioned that they were using their eyes (not their ears, for example) and were learning this task quickly, presumably compared to something else that is less quick.

It would also help to know what you think it is about the world that they learn — specifically, not about counting things in the world, since that’s being rejected. It isn’t terribly helpful to just get a vague gesture at some other mystery set of “things in the world” that it may or may not be.

It’s kind of funny … it doesn’t seem like much of a problem when you have more than one emprically adequate theory. It’s like the “problem” some people have of owning two nice houses, both satisfactory, both fully paid off…. More often, the issue is that people are just hoping to come up with a single intelligible one that also makes good predictions.

Anyway, if this were an episode of Highlander, so there needs to be only one (which is deemed correct, since we only have the one world to be correct about), then unfortunately it may simply be impossible to distinguish between them empirically. It’s not logically necessary of scientific theories in general, meaning your approach need not always work. But there can be other useful features, besides empirical adequacy/predictive power, that could help to make the decision a little easier: simplicity, parsimony, making room to develop bigger and badder theories in the future, making new technologies, which one lets you write more articles and get more grant money (preferably while doing less work), and so forth.

For some real fun with behaviorism, have a look at “Applied Behavioral Analysis” — it’s touted as “therapy” for Autistic kids. Autistics, of course, have a LOT to say about ABA, and NONE OF IT is good. It’s basically “abuse the kid until they learn to act neurotypical”.

Yes I could make Jake drool, by eg preparing the dogs’ breakfasts or preparing meat for us, and catching it would be reasonably easy as he knows to sit still in the same place or he will not get spoon licks or scraps. This is because even with our higher than normal worksurfaces he could easily take things off them or nudge your elbow when you were using a knife, so he was trained not to do that as soon as we got him; we can leave meat on a work surface were he could reach it and he won’t try to get it, unless he knows it’s dog food. I couldn’t make Thorn drool to order, she very rarely (?if ever?) drools. I guess it depends on the dog not just the breed.

I hope that makes sense I’m very tired. I’ll look at the question again in the morning.

consciousness razor@#10:

You seem to put a lot of weight behind the word “generalize.” We’re animals. There are things animals do, which can be studied. Other animals are obviously not the very same thing as humans (not to mention that individuals themselves aren’t identical), but there may nonetheless be a huge number of significant patterns which could help us understand the world a little better. So let’s see what we find and “generalize.”

I am referring to the tendency to generalize one animal’s behavior as possibly being representative of other animals, in a certain situation. We may learn there are significant patterns, and we may not but – so what? Doesn’t it seem reasonable to ask whether some behavior we observe in animal A is likely to be similar to animal B and have a theory that we can confirm or disconfirm, first? Otherwise we’re just gathering observations and, if we detect similarities, we have no theoretical basis to make any assumption other than, “huh, these two animals do similar things in similar circumstances.” Again: so what?

You appear to be characterizing my complaint as a straw-man argument, which I don’t appreciate. I’m not just throwing rocks at some experiments for the fun of it; they’re experiments that were undertaken without any framework in which we’d learn anything worth doing the experiment in the first place. If we’re experimenting on people or other animals, then we’re really just playing with their lives to see what happens. Why not do what Nikko Tinbergen and the ethologists suggest, which is observe the animals’ normal behaviors in the circumstances which the animals normally experience? That way, we learn what Animal A does in a given situation; there’s plenty of knowledge to be had from that. I.e.: if you want to know how Graylag geese behave when they have a chick and a predator is threatening the chick, you can observe that behavior as it happens – putting a Graylag goose and its chick in an artificial situation tells you damn near nothing. In fact, if it’s a Graylag goose, its response to a novel situation may appear to be random, because that’s what Graylag geese appear to do in novel threat situations. Other geese do not. So, suppose we make an observation that “in this situation, Graylag geese do X” and generalize it to all geese? Let alone humans?

When people read pop psychology experimental results, like John Calhoun’s mouse crowding studies, they are looking for ways to generalize that behavior – imagining that maybe other animals will behave likewise. Mostly, they think maybe it shows something about how humans will behave. But even mice and rats don’t behave the same way in the same situations, never mind individuals, and certainly not humans. None of that even touches on the question of whether these behaviors are learned or instinctive or a mix of the two (which seems most likely). So, if these experimental observations cannot be generalized, then what are we learning from them? Aside from (for example, in the Calhoun experiments) “mice in a highly unusual and constructed situation do not behave like mice do in nature.” Big deal.

Or just failing to consider/understand the strongest case that can be made for the thing you’re opposing.

I just want to check. Are you trying to imply I am being dishonest?

It’s not my job to choose the strongest case for the thing I am opposing. Actually, when we’re talking about scientific theories and experiments, all it takes is a single counter-argument to put the whole thing in doubt. I’m not responsible for going, “well, this experiment would be worthwhile if it were ${somehow different}” let the experimenter figure that out and, in the meantime maybe they should retract their work or acknowledge that they didn’t defend it adequately. Perhaps we have a different understanding of how the scientific method works.

You don’t seem to have an issue assuming that there is a mechanism.

I’m willing to assume that behaviors that appear strongly non-random are non-random. That’s what we observe. As I said, I think the behaviorists have the right approach.

Instead, what you want to contest, apparently, is which specific mechanism it was that some specific people happened to propose, as well as the logical or empirical justification for that …

Well, yes. If there appears to be something governing a behavior, and it appears that the behavior is consistent and non-random, why wouldn’t we assume there’s a mechanism of some sort governing the behavior? Then, it’s up to whoever’s concerned with it to hypothesize how that mechanism works and devise experiments intended to reveal how it functions. Whether their hypotheses and experiments make the case well, is their problem.

That’s pretty straightforward, I think, and I don’t see how science can work any other way. It’s the old “burden of proof is on the proposer of the proposition” thing, isn’t it?

What do you think would constitute an ability to do counting-like stuff, if it isn’t discerning something like bigger/smaller or more/less?

Ah, I think I see the disconnect. I am unconvinced that being able to discern bigger/smaller and more/less are an example of counting-like stuff. Being able to discern bigger/smaller could be a much simpler function than counting. I could hypothesize a couple of things it could be, which don’t involve counting but the easiest answer is that discerning more/less could be a “compare roughly how big something looks.” That capability may be something that could contribute to a counting-like capability, but it’s not one. Probably at this point we’d need to agree on a definition of “counting-like ability” that was not recursive but it’s not my problem to do so.

What do you think would constitute an ability to do counting-like stuff, if it isn’t discerning something like bigger/smaller or more/less?

I don’t know. That’s the point. I am the one that is unconvinced that being able to say something is bigger or smaller than something else implies an ability to do counting-like actions. I’m comfortable with the idea that being able to say something is bigger or smaller than something else implies an ability to compare sizes of things. Does that ability depend necessarily on being able to do counting-like behaviors? It might not. It might. I’m trying not to speculate.

I don’t know how counting-like stuff could happen without the use of some such set of concepts about exactly that type of relation.

Is that an argument from ignorance?

It’s possible that it’s an innate ability, which just gives a bigger/smaller signal. I can imagine how one could lash a bigger/smaller answer into an ability to order things by size. What if we have neurons in our brain that specialize in returning a boolean value for comparing the sizes of two things? I’m not saying we do – but it’s just about as ridiculous as the option that being able to compare sizes of things implies the potential for doing counting.

Even if you were to say that being able to compare sizes of things implies the potential for doing counting, that still doesn’t argue that that’s what’s actually happening. There could be some other mechanism that does not carry that implication. There might not. But I don’t see how we can point at the potential and say “that’s how it happens.”

First, you were the one to propose that we could say (at least for the sake of argument) that babies can discern bigger/smaller or more/less.

No, I said that, absent evidence otherwise, we could hypothesize such a thing and that it would be completely vacuous. We can come up with hypotheses about what’s going on until the cows come home and die of old age, but if we have multiple possible mechanisms for how something might happen, and we cannot eliminate all but one, then it seems to me that we can’t say we have attiributed that effect to that cause. We can have strong suspicions, sure. But we have not got enough knowledge to claim we understand the mechanism.

Oh, I think I just thought of an example that may help you understand what I am saying: Clever Hans. I don’t know if you are familiar with Clever Hans the “horse that could count.” It turned out that the horse couldn’t count at all, but exhibited behaviors that were indistinguishable (to some people at that time) from counting. In actuality, the horse would simply signal digits until he saw the body language of his trainer indicate he had the right number. The horse had no counting capability at all but exhibited counting-like capability. I might hypothesize that he had an “on/off” ability. So, we have two theories now:

1) Clever Hans can count

2) Clever Hans can read body language

The way to proceed is for the people who believe Clever Hans can count to re-formulate their experiment to factor out the newly-raised objection to their experiment.

If discerning (whatever exactly that means) between bigger/smaller or more/less is supposed to be evidence that their eyes function and that their brains quickly learn certain things about the world around them, then you should have mentioned that they were using their eyes (not their ears, for example) and were learning this task quickly, presumably compared to something else that is less quick.

Eh, I was just making up other hypothetical abilities for the babies to have. It’s all the rage. If I were actually saying they had those abilities it would be my job to convince you that they did. I don’t just get to say “oh they use their ‘bigger sense'” – any more than I get to say “they use their ‘counting sense'”

I’m quite sure I didn’t explain myself properly. Sometimes I fail to do that. This is a blog not a thesis defense.

It would also help to know what you think it is about the world that they learn — specifically, not about counting things in the world, since that’s being rejected. It isn’t terribly helpful to just get a vague gesture at some other mystery set of “things in the world” that it may or may not be.

I am not seriously proposing there is such a sense. I’m saying “you don’t get to just suppose there’s such a sense and move on, without considering problems with your evidence that there is such a sense.” I created that whole example as a way of showing how hard it is to prove that there is a hypothetical capability by just hypothesizing it and saying, “SEE!?” How does being able to look at more or fewer dots show that someone has a “counting-like sense” when it might just as easily show that someone has a “like more dots sense”?

it doesn’t seem like much of a problem when you have more than one emprically adequate theory

OK, let me try a less subtle example:

Hypothesis: babies get “look at the picture” beamed into their heads from distant aliens on Sirius B.

Hypothesis: babies have a “counting-like” capability

Hypothesis: babies just like more visually cluttered pictures because they have a sense of taste that’s oriented that way

Since all three hypotheses attempt to establish a unique cause/effect relationship between a mechanism and how the baby behaves, only one hypothesis can be true at best. They could all be false; there could be hundreds or millions of other theories. So, whoever is promoting any particular theory needs to come forward with experimental evidence that their theory is the right one. It is my opinion that has not happened here. Maybe you’re comfortable that babies can do counting-like behaviors. That’s OK, you’re welcome to it.

But there can be other useful features, besides empirical adequacy/predictive power, that could help to make the decision a little easier: simplicity, parsimony, making room to develop bigger and badder theories in the future

Well, sure. One can also choose to believe in whatever theory is prettiest, or sounds best.

How are we supposed to decide which theory we accept, when there are multiple theories? Evidence and experiment, presumably. We can create an infinite barrage of theories – the question is how plausible they are. In this case, when we’re talking about pretty thin results (“in the upper 50% of their class”) and a dramatic hypothesis (“6 month old babies can sort of count”) I’m not convinced. Maybe you are/aren’t.

ridana@#2:

What’s so hard to believe about a drop counter? (I’m pretty sure the tech existed for it back then, it’s a pretty simple device) The dogs were surgically implanted with cannulas to collect the saliva. They weren’t just holding a bucket under their mouth.

Well, I’ll drop a posting about that tomorrow.

Surprisingly, the pictures illustrating the experiment don’t appear to match the photographs of the experiment.

Illustrations of hoses coming from dogs and going to counting-devices don’t appear to bear any resemblance to what was going on. It looks more like a drool-catcher with graduated markings. That’s hardly a “drop catcher”.

I can imagine a “drop counter” though. It would be a precision piece of machinery with a carefully calibrated drop-former which let drops fall onto a counter-balanced arm that would actuate a counter under the weight of a drop impacting. I can already think of several things that would go wrong with such an instrument (multi/partial drops, dry air, vibration, occlusion of the drop-former, differences in the thickness of dog drool…)

The dog pawing at the fucker because it looked interesting/was in the way/it was bored/it really didn’t like being held in the apparatus/it heard a noise outside/it thought it ought to be dinnertime anyway.

@ 8 Sam N

I gave the paper a quick skim but I am just about falling asleep at the keyboard so I am missing things but I think it needs a good fisking from someone familiar with the area. An n = 48 is not that great and some of the r’s do not look that large. There seems to be some mention of a reduced sample size in some of the testing at three years of age that I am too tired to check out. I did not notice anything about baseline controls but I need to read the thing when I am fully concious.

There is, at least, one regression that does not make seem to make any theoretical sense but I don’t know the area.

NAoS support did pass through my mind

@ Marcus

I will not further belabor the fact that Pavlov’s results are part of the core of psychology’s epistemology: operant conditioning is considered to be a model for how learning takes place.

Pavlovian conditioning is usually referred to as “Classical conditioning” it is not operant. Skinner’s research, for example, was in the area of “operant conditioning”

I have always thought that Pavlovian (classical conditioning) was pretty much a dead end though it probably has specialized uses that I am not aware of.

Re dogs: I’ve been fortunate to have a number of them over the years; only one was a drooler (Rhodesian Ridgeback “Flynn”), and it wasn’t drops, it was a stream — like a tap — if he thought he had a chance of something. When the chance was no more, the drool stopped.

My current one (Staffy “Igor”) just sits and hopes hard, but no drool whatsoever. Same treatment, of course.

—

In passing, I’d much rather Pavlov had experimented on humans than on dogs; dogs deserve better than that. I don’t elevate humans above dogs just because I happen to be human.

[OT]

PS I don’t recommend getting a hunting breed dog if you live in a rural area, lovely as they may otherwise be. They just can’t help but to hunt.

Learnt that the hard way.

I wonder how you would do a control on the “baby looking at dots” experiment. Use many different animals? Do llamas like looking at images with more dots? What about zebra fish, or crows, or sheep? If all those other animals prefer looking at more dots rather than less dots, does that mean they can count? I’m not sure that follows.

I do think people tend to put themselves too much into these experiments and assume way too much, but at least here they are using other human beings. I really have to wonder when I read, for example, that cattle don’t usually eat a certain poisonous plant because it “tastes bitter”. How do they know what it tastes like to the cow? Do cows perceive the taste of things the exact same way that humans do?… seems like they might be guessing.

kestrel:

Um, change “because it “tastes bitter”’ to “because they don’t like the taste” and your objection vanishes. Me, I like gin and bitters.

Dunno. Presumably, the reference is not the qualia of taste, but rather to the homologous sensory system. In the taxonomy of species, we’re pretty closely related.

(Ever heard of cowpox?)

Baby: WTF is this? Mum said we were going out for a bit of fun, and all I get is a bunch of dots? Jesus. Someone explain adults to me.

Marcus @#14:

While I can think of a number of ways to build a drop counting device with early 20th c. tech, what matters is what Pavlov says he did. You can find one of his lectures about it here. About 4 paragraphs down is an explanation with an illustration of his device, which I can’t follow for the life of me. Make of it what you will.

He also notes:

I didn’t read the entire page (afraid of running into more things about his work I’d rather not know), but some parts of it were curiously interesting, like building a fucking moat (ok, a trench) around the research facility to reduce outside stimuli.

Marcus:

I don’t get why you think you need something in addition to learning stuff. Did you have some other kind of scientific thing that needed doing?

You have an answer when someone comes along to ask “but how do you know these two animals do similar things in similar circumstances?” You can respond with “I know this from empirical observations.” And if it seems like somehow they still don’t get the point of it all, you could say “that’s a way to start doing science, not with some wacky ‘theory’ about nothing that has ever been observed.” And then you stare at them until they go away, so you can go back to learning more stuff about the world.

So, of course, we should do so carefully and ethically. You play with rocks just to see what happens; and if the rock is unharmed (as the evidence suggests), there’s no problem. It’s the same with having babies stare at dots, for instance: they’re unharmed. Since I’m not condoning anything unethical, I’m not sure where you think this is going, but I’ll leave it there.

Did I ever say anywhere that you shouldn’t do that, or did I give you any reason to believe this is what I thought?

You make it sound as if that’s a problem. It could be true that other animals will behave likewise, and saying “maybe so” is entirely correct. You can do further observations/experiments to find out what those indicate. Sometimes, you probably shouldn’t be too surprised to get similar results. Sometimes, you probably should be. It depends.

No. If you were deliberately strawmanning, that would imply dishonesty. Simply failing to comprehend something isn’t dishonesty. (And that’s not how “strawmanning” is normally interpreted, since people typically take offense and assume the worst, which is why I added that as an alternative.)

I don’t care what your job is, but opposing something for silly reasons is not a good idea.

If your counter-argument is incoherent or irrelevant (like a strawman argument is), then in fact it doesn’t put the whole thing in doubt. It may make you personally have doubts, for whatever silly reasons you’ve contrived, but that does not actually matter in the grand scheme of things.

But that’s just you presuming that evidence and experiment are always enough to decide the matter. What I was saying is that it ain’t necessarily so. The only options at that point are using other criteria which don’t depend on distinguishing between them empirically, since observing is not the only thing we’re capable of doing (i.e., we can think and so forth). If this made you throw up your hands up and say “but I presumed otherwise,” then I doubt most people would care.