A friend of mine retired from an IT executive job and she and her husband decided to become wealthy capitalists in their retirement. Since the evils of capitalism are a frequent topic here on FtB, maybe it’s a good idea to do a quick explainer of how a few of those evils work. These are the simple ones, and I’ll describe them as cleanly as I can so you can understand what’s going on when you hear about it elsewhere.

The basic idea of asset stripping is that if you can find anything that is worth more than its owners realize you buy it for what they think it’s worth, sell it, and then are left with a profit. This is not “theft” it’s just “the seller mis-priced what they were selling” so it’s moral behavior for capitalists. In fact, it’s practically sanctified behavior.

Let’s take an example: XYZ Framis Corp has been a family-run business for 75 years and is a solid player in the global framis market. They have been pretty profitable for those 75 years, have good relations with the unionized workers, and have built up a well-funded pension fund. In fact, because the founders believe that laborers should be cared for in their old age, there is nearly $25,000,000 in the pension fund. An asset stripper notices this, and notices the market price of XYZ Framis Corp shares takes a dip; the company’s market capitalization drops. Let’s say XYZ Framis Corp shares total value is $250,000,000. One day it drops to $200,000,000 because the stock market is having a bad day. A group of asset strippers borrow $200,000,000 on a short-term loan then buy a controlling interest in XYZ Framis Corp – let’s say they buy it all (to keep things simple) – they’ve just bought $275,000,000 for $200,000,000. So they immediately start firing workers, sell off the tooling and facility, and pocket the $25,000,000 in the pension fund. Then they sell the remains of the company for whatever they can get for it – anything in the $200,000,000 range will do. What they really wanted was the pension fund. Then they pay off whoever loaned the $200,000,000 and they have a tidy profit; they have done no actual work, added no value to anything, destroyed a profitable business, and killed off all the framis-making jobs in the USA.

Let’s take an example: XYZ Framis Corp has been a family-run business for 75 years and is a solid player in the global framis market. They have been pretty profitable for those 75 years, have good relations with the unionized workers, and have built up a well-funded pension fund. In fact, because the founders believe that laborers should be cared for in their old age, there is nearly $25,000,000 in the pension fund. An asset stripper notices this, and notices the market price of XYZ Framis Corp shares takes a dip; the company’s market capitalization drops. Let’s say XYZ Framis Corp shares total value is $250,000,000. One day it drops to $200,000,000 because the stock market is having a bad day. A group of asset strippers borrow $200,000,000 on a short-term loan then buy a controlling interest in XYZ Framis Corp – let’s say they buy it all (to keep things simple) – they’ve just bought $275,000,000 for $200,000,000. So they immediately start firing workers, sell off the tooling and facility, and pocket the $25,000,000 in the pension fund. Then they sell the remains of the company for whatever they can get for it – anything in the $200,000,000 range will do. What they really wanted was the pension fund. Then they pay off whoever loaned the $200,000,000 and they have a tidy profit; they have done no actual work, added no value to anything, destroyed a profitable business, and killed off all the framis-making jobs in the USA.

Capitalist apologists might say that the asset strippers just made the global framis market more efficient. But that’s bullshit – it was really all about legally stealing the $25,000,000 pension fund without doing any work for it except signing papers and doing some handshakes. Time left over for a round of golf.

When a Chinese company rises to prominence in the global framis market following the unexpected collapse of XYZ Framis Corp, capitalist apologists point to China and say “they stole our jobs!”

The amount of additional money you can borrow against an asset is called your “leverage.” So, a “leveraged buy-out” is when you buy a business using another business as collateral. In a bit I’ll explain what leveraged buy-outs look like if you’re collecting trailer parks. The “junk bond king” Michael Milken, who has now reinvented himself as a multi-hundred millionaire philanthropist, popularized the “leveraged buy-out” in the late 70s and 80s, and triggered a huge bubble in asset values as everyone inflated what their assets were worth, so they could get bigger loans to buy bigger assets. It all collapsed and a lot of people lost everything. As happens to the small fish that swim with the big sharks in capitalism.

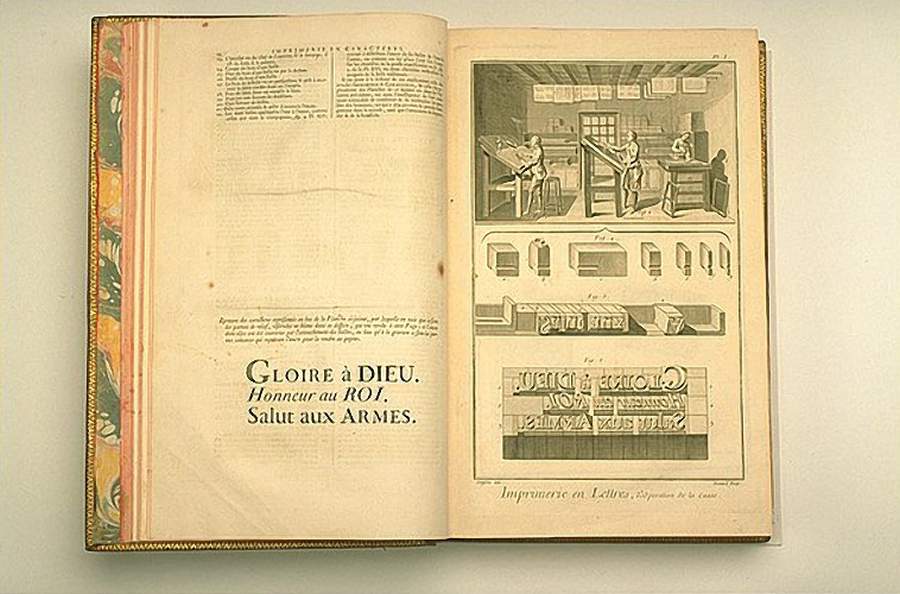

Asset stripping happens in lots of ways at lots of levels. My father used to turn purple with rage when he’d see old books (like a volume of Diderot’s encyclopedia) in art stores that had had the illustrations cut out, framed, and sold as individual art-works. If you can buy a copy of the encyclopedia for $1,000 and it has 200 illustrations in it that you can get $25 apiece for, you’ve just made $4,000. It was just a dumb old book, right?

Here’s another term: “margin call.” Let’s say you buy the encyclopedia with a $1,000 loan from your fellow capitalist buddy. Here’s a trick: you use the encyclopedia as collateral for buying the encyclopedia! So you tell Capitalist Bob “hey Bob, lend me $1,000 for a year. I’ll pay you back $1,250 at the end of the year.” and Capitalist Bob says “what is your collateral for that loan?” (good capitalists don’t trust eachother) You say, “I have a copy of Diderot’s encyclopedia worth $1,000.” He loans you the money, you buy the encyclopedia, sign a contract with Capitalist Bob that at the end of the year he gets $1,250 or he ‘forecloses’ on your encyclopedia. Then you get out a mat-cutter and start whacking pages out of the poor, unfortunate book. Capitalists refer to this as “margining out” – you’re gambling that you can make enough to pay back the loan on time, and that everything from then on will be profit. But suppose nobody wants to buy the pictures; you’re margined out and Capitalist Bob calls and says, “hey, it’s time for my money or the book.” That’s a margin call. It’s when the value of the assets you used to secure a loan have changed, and are no longer worth the price of the loan. Capitalist Bob is going to send Ivan the Bonecrusher over to visit you if you don’t come up with the cash.

Here’s another term: “margin call.” Let’s say you buy the encyclopedia with a $1,000 loan from your fellow capitalist buddy. Here’s a trick: you use the encyclopedia as collateral for buying the encyclopedia! So you tell Capitalist Bob “hey Bob, lend me $1,000 for a year. I’ll pay you back $1,250 at the end of the year.” and Capitalist Bob says “what is your collateral for that loan?” (good capitalists don’t trust eachother) You say, “I have a copy of Diderot’s encyclopedia worth $1,000.” He loans you the money, you buy the encyclopedia, sign a contract with Capitalist Bob that at the end of the year he gets $1,250 or he ‘forecloses’ on your encyclopedia. Then you get out a mat-cutter and start whacking pages out of the poor, unfortunate book. Capitalists refer to this as “margining out” – you’re gambling that you can make enough to pay back the loan on time, and that everything from then on will be profit. But suppose nobody wants to buy the pictures; you’re margined out and Capitalist Bob calls and says, “hey, it’s time for my money or the book.” That’s a margin call. It’s when the value of the assets you used to secure a loan have changed, and are no longer worth the price of the loan. Capitalist Bob is going to send Ivan the Bonecrusher over to visit you if you don’t come up with the cash.

When talking about real estate loans that’s what people are talking about when they say they are “under water” on a loan: I buy a house for $1,000,000 and then borrow $750,000 against the house so I can start a methamphetamine business. But the feds raid my meth lab and I lose all my assets. Now I ‘own’ $250,000 of a $1,000,000 house. But – because this is a messed-up story about capitalism, it turns out that the $1,000,000 house is built on top of a toxic waste dump that the seller neglected to mention to me. The best I could get if I sold it would be $100,000. I am now “under water” by $650,000 because if I sell the house I still have to pay off the loan, but my asset’s value re-adjusted and now I am screwed. Then comes the “margin call” when Max The Merciless – the guy I borrowed the money from – discovers that my meth lab was busted and I no longer have assets enough to collateralize my loan.

So, asset stripping and margining out are basically forms of gambling. If you’re rich already, you can play these sorts of games without danger because even if you lose you have enough assets somewhere else that you can survive if you’re margined out and one of your loans goes underwater. That’s what Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital was: a large pile of money that served as a base of collateral from which Romney could buy businesses, strip their assets, break them apart, and sell the shattered remains. You know those jobs everyone’s talking about? That’s what Bain Capital is exactly not about: it created a job for Mitt Romney and some lawyers, and otherwise it just shut businesses down. It’s the business equivalent of buying a beautiful book and cutting out the pages with illustrations, then throwing the pages which are just text in the dumpster.

So, asset stripping and margining out are basically forms of gambling. If you’re rich already, you can play these sorts of games without danger because even if you lose you have enough assets somewhere else that you can survive if you’re margined out and one of your loans goes underwater. That’s what Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital was: a large pile of money that served as a base of collateral from which Romney could buy businesses, strip their assets, break them apart, and sell the shattered remains. You know those jobs everyone’s talking about? That’s what Bain Capital is exactly not about: it created a job for Mitt Romney and some lawyers, and otherwise it just shut businesses down. It’s the business equivalent of buying a beautiful book and cutting out the pages with illustrations, then throwing the pages which are just text in the dumpster.

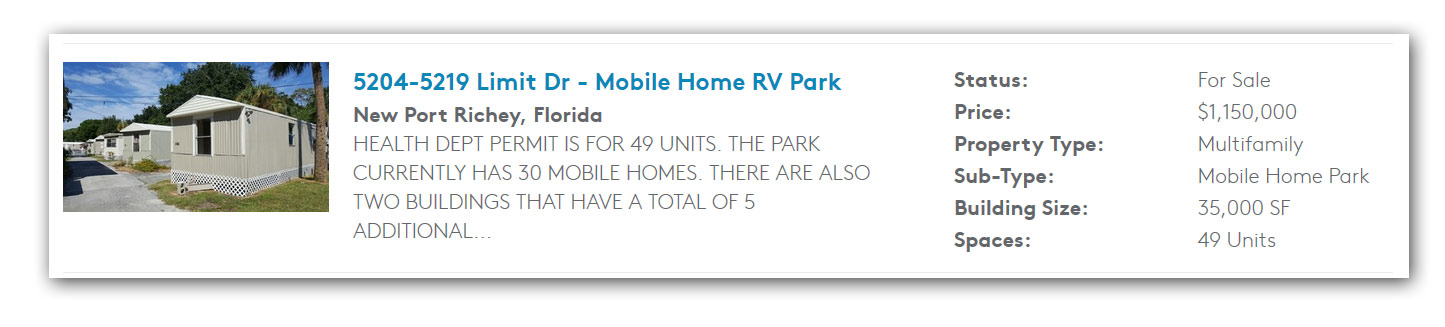

Then, you have the roll-up experts. That’s what my friend did when she retired: she bought a trailer park. It wasn’t a very big one, and it wasn’t a very nice one, but it was what she and her husband could afford to gamble on. Then, they invested some money in making it look better: paint, driveways, some landscaping, and a property code that all the trailers had to look good. So let’s say she bought the trailer park for $750,000 and spends $100,000 prettying it up. That’s mighty pretty. Then, she goes to the bank to get a loan to buy another trailer park, up the road; it’s worth $1,500,000. So she gets the first trailer park assessed as worth $1,250,000 and gets a loan for the second trailer park with the first trailer park as collateral. If you’ve done the math you noticed there’s $250,000 missing – she took a home equity loan against her house for that (margining herself out a bit) and is paying $2,000/month on that home equity loan. Then, she raises the prices on all the denizens of the two trailer parks – it doesn’t take much – until she’s bringing in $5,000 more per month. Clever, huh? In 10 months she’s paid off the home equity loan and can buy the trailer park over the hill by cleaning up the second trailer park a bit, and doing the same routine. Last time I checked with her, she owned most of the trailer parks in a large area, and had raised the prices just a little bit, at all of them. When the financial crisis hit and interest rates dropped, she re-financed all the debt on all the trailer parks and her profit margins were high enough that she’s probably paid them all off, now.

Then, you have the roll-up experts. That’s what my friend did when she retired: she bought a trailer park. It wasn’t a very big one, and it wasn’t a very nice one, but it was what she and her husband could afford to gamble on. Then, they invested some money in making it look better: paint, driveways, some landscaping, and a property code that all the trailers had to look good. So let’s say she bought the trailer park for $750,000 and spends $100,000 prettying it up. That’s mighty pretty. Then, she goes to the bank to get a loan to buy another trailer park, up the road; it’s worth $1,500,000. So she gets the first trailer park assessed as worth $1,250,000 and gets a loan for the second trailer park with the first trailer park as collateral. If you’ve done the math you noticed there’s $250,000 missing – she took a home equity loan against her house for that (margining herself out a bit) and is paying $2,000/month on that home equity loan. Then, she raises the prices on all the denizens of the two trailer parks – it doesn’t take much – until she’s bringing in $5,000 more per month. Clever, huh? In 10 months she’s paid off the home equity loan and can buy the trailer park over the hill by cleaning up the second trailer park a bit, and doing the same routine. Last time I checked with her, she owned most of the trailer parks in a large area, and had raised the prices just a little bit, at all of them. When the financial crisis hit and interest rates dropped, she re-financed all the debt on all the trailer parks and her profit margins were high enough that she’s probably paid them all off, now.

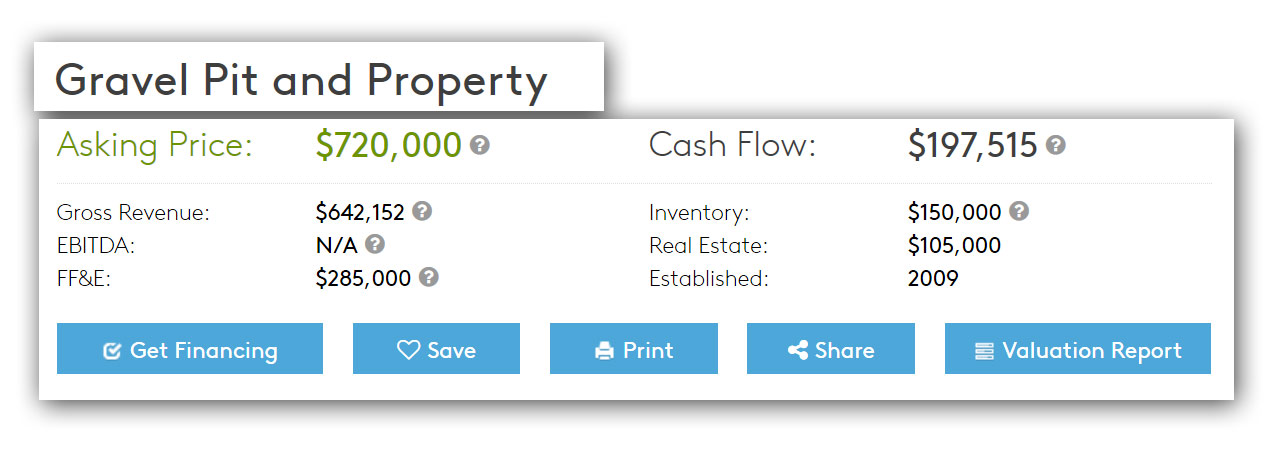

I know another guy who did a roll-up and it was brilliant; he is now quite wealthy. His big realization was this: the cost of diesel fuel is going up and will never come back down. From that, he concluded that the cost of shipping gravel for construction and lawn and garden decoration was going to be affected by the cost of diesel fuel. He looked around and found an area that was turning into nice suburbs and had a lot of high-end homes being built – and bought the local gravel pit/quarry. Then, he raised prices sharply and blamed the cost of fuel. He played his gamble perfectly: none of the builders were willing to pay the additional fuel cost and time to have gravel and rock trucked in from another county so they complained and passed the cost on to their customers. The result was that his gravel pit started bringing in a lot more money, which made it worth more on paper so he used the first gravel pit as collateral to buy the only other gravel pit in the county. Then, he controlled the price of gravel and as long as diesel fuel costs went up, he could raise the price per ton to the point where it was just what the market would bear, below the point where it was cost-justified to truck gravel in from 30 miles away. You know what happens next: he bought another gravel pit.

I know another guy who did a roll-up and it was brilliant; he is now quite wealthy. His big realization was this: the cost of diesel fuel is going up and will never come back down. From that, he concluded that the cost of shipping gravel for construction and lawn and garden decoration was going to be affected by the cost of diesel fuel. He looked around and found an area that was turning into nice suburbs and had a lot of high-end homes being built – and bought the local gravel pit/quarry. Then, he raised prices sharply and blamed the cost of fuel. He played his gamble perfectly: none of the builders were willing to pay the additional fuel cost and time to have gravel and rock trucked in from another county so they complained and passed the cost on to their customers. The result was that his gravel pit started bringing in a lot more money, which made it worth more on paper so he used the first gravel pit as collateral to buy the only other gravel pit in the county. Then, he controlled the price of gravel and as long as diesel fuel costs went up, he could raise the price per ton to the point where it was just what the market would bear, below the point where it was cost-justified to truck gravel in from 30 miles away. You know what happens next: he bought another gravel pit.

What usually happens with these deals is that someone comes up with the idea, does it, and makes a ton of money. Then, a few more people do it, and the marks catch on, realize that they haven’t been valuing their assets correctly, and raise the prices (aka: “a market correction”) – as soon as it’s no longer possible to buy assets that are undervalued, there’s no point in these types of manipulations because the cost of entry is the same as the value of the exit, so there’s no easy money to squeeze out of the system. That’s really the important thing to understand: none of these shenanigans add any value to anything. It’s just squeezing out profits that people had overlooked – perhaps because they were, you know, trying to build a sustainable business that had happy employees. Capitalism’s efficiency comes mostly from squeezing out that happiness – hey, it’s “unrealized assets” baby.

I tell you these little stories to explain how metastatic capitalism spreads like cancer and destroys businesses and magnifies inequality by taking advantage of poor people who aren’t mobile enough to leave and find another trailer park. Or, the union workers at XYZ Framis Corp, who thought they had a pension and a steady job, suddenly find “their jobs stolen by the Chinese.” Or, why some commodity prices suddenly spike for no apparent reason. Remember ENRON? That was a commodity roll-up in the energy market: an energy company that kept getting bigger and valuing itself higher and higher so it could buy more small companies. These things work as long as nobody reads the books carefully.

And now you know why Donald Trump keeps people from looking at his books. He’s probably a billionaire in terms of deliberately inflated asset values, but what is he actually worth? This morning, I had a bowel movement that was probably worth more than Donald Trump, if you balanced his assets against his debts and risk. If you’ve been reading between the lines, Jared Kushner’s real estate portfolio is margined out and he’s sweating because he’s got a loan on a property that he’s not being able to sell in order to cover the cost of servicing his leverage. In other words: he’s a gambler and right now he’s losing and everyone knows he’s losing so they’re all watching to see what happens. Capitalists are like sharks; they love to watch one of their own fumble so they can rip them apart in a bloody scrimmage that leaves everyone grabbing at chunks of meat. Then they go for a round of golf.

And now you know why Donald Trump keeps people from looking at his books. He’s probably a billionaire in terms of deliberately inflated asset values, but what is he actually worth? This morning, I had a bowel movement that was probably worth more than Donald Trump, if you balanced his assets against his debts and risk. If you’ve been reading between the lines, Jared Kushner’s real estate portfolio is margined out and he’s sweating because he’s got a loan on a property that he’s not being able to sell in order to cover the cost of servicing his leverage. In other words: he’s a gambler and right now he’s losing and everyone knows he’s losing so they’re all watching to see what happens. Capitalists are like sharks; they love to watch one of their own fumble so they can rip them apart in a bloody scrimmage that leaves everyone grabbing at chunks of meat. Then they go for a round of golf.

Adam Curtis did a great documentary about the first generation of asset strippers, called The Mayfair Set. It’s got a lot of familiar characters from the 1980s in it but it’s London/England-centric.

It’s fascinating stuff. Curtis charts how Britain’s real estate market and industry were gutted by asset stripping capitalists, who leapt in when the government lost power because of the downturn in value of the Pound Sterling in the 70s and 80s. I don’t recall if it has the story of George Soros’ run on the Bank of England (I think it does) but … Soros basically triggered a margin call on the Bank of England and the government had to turn on the printing press to prevent a collapse, which basically made Soros’ options against the Bank of England become worth real money.

Is this interesting to you? If it is, shall I explain options and derivatives next?

IF I remember right this also happened to health care non profits. They had all this reserve cash.

Or maybe it was just health care organizations in general. It was a long time ago.

I’ve always been interested in these types of ‘economic principles’, if that’s the correct way to phrase it. Your explanation has the benefit of being informative and not skewed with the perspective of running dog capitalists, i.e. it’s not covered in bullshit, so please continue.

I find word etymology inherently interesting. In Russian there’s a word “прихватить” (spelled with English letters: prihvatit’; meaning: to seize, to grab). In Latvian there’s a verb “privatizēt” (meaning: to privatize), and a noun “privatizācija” (meaning: privatization).

In 1990ties Latvians crated a new word—“prihvatizēt” (as a verb) and “prihvatizācija” (as a noun). This new word was a combination of the Latvian word “privatizēt” and the Russian word “prihvatit’.” As you can see, the beginning of both words is the same, except for the “h” sound in the Russian word. The meaning of Latvian word “prihvatizēt” is “to use the privatization process in order to seize state assets.” In 1990ties in Latvia there was this whole privatization process. Assets (real estate, companies) that used to be owned by the Soviet state were getting privatized. Plenty of nasty people (aka: capitalists) became millionaires as a result. The way how they did it was basically the same as what you described in this blog post: they used the privatization process to obtain some factory (the way how politicians engineered the process allowed businessmen to obtain factories for very little money). Afterwards they just fired all the workers and sold all the machinery and buildings from the factory. And that’s how the first Latvian millionaires earned their cash in the 1990ties. Fired workers couldn’t do anything; they could only accept their fate. And of course people also invented an entirely new word to describe this business model.

Speaking of etymology, Latvian word for violence is “vardarbība.” It’s a compound word. “Vara” means “power” in Latvian. “Darbība” means “an action.” Latvian word “vardarbība” means literally “exercising one’s power.” Apparently, back when people coined this word, whoever had power tended to also abuse it. And now we have politicians and capitalists talking nonsense about how those people who have power use it for the benefit of all the citizens. Yeah, right, they sure do.

By the way, I forgot to mention another trick that the well-rounded capitalist might play. Consider Gravel Pit Guy, now he owns all the gravel pits in a region; he has 3 gravel pits – so he shuts two down and lays off the workers. Now, he’s still got the valuable assets (gravel in the ground) and now that there is only one source for gravel, naturally, the price goes up a little. His trick, then, is to manipulate the price of gravel so that nobody gets the great idea “hey! I’ll open my own gravel pit!” – if he’s a really clever capitalist, he then buys the local representative with a donation of $100,000 for his next election campaign, and the representative sneaks across legislation that says that gravel-pits are regulated because reasons and you need to jump through flaming hoops wearing a chicken suit in order to open a new one. That technique is called “regulatory capture” – it’s when the industry being regulated buys the regulator or runs their nephew for the regulator’s seat.

Isn’t capitalism great? It’s so efficient, and it squeezes so much efficiency out of the market. It’s so efficient everyone must play a round of golf!

Asset stripping happened to a lot of British breweries, the ones that had city centre sites or even edge of city centre sites dating from the Victorian era, especially if they were owned by families where most of the current owners weren’t involved in the day-today business, but just took their dividends. We lost many jobs, some great beers and some gorgeous buildings. Sometimes the buildings were retained because they were listed, but turned into flats. It really pisses me off.

But how is the market “more efficient”? I don’t get this one. What does efficiency mean for the market? That there is one source of framis less in the world? If Framis Corp was profitable then it should, speaking capitalistically, be “fine” even if it might have been more profitable. (Making the Corp more profitable would presumably have raised the effieciency of the company, not the market as a whole.) At most it would mean all the other framis producers would now be a little more profitable as they get a bigger share of the demand without having to compete for it. Is that all “efficiency” is here? “More for me!” (Or, for the asset stripper, more for someone else who’ll be strip-mined later.)

In the same way as the bacteria eating my brain would be, yes.

jazzlet@#6:

Asset stripping happened to a lot of British breweries

Ugh, yes. And that’s how you wound up with a great big roll-up that owns everything. Same thing in the US.

What appears to happen is that the wall street guys learn a particular market well enough to spot “unrealized value” (i.e.: money nobody has grabbed, yet) in that market. Then, they move in and squeeze it as hard as they can. I suppose that once someone learns how to value a brewery’s finances they can walk in and quickly spot the ones that are take-over candidates.

As I am sure you know, the reason I am pointing all of this out is because those “efficiencies” are jobs and equipment. There is absolutely no reason at all that the brewing industry needs to be so “efficient” that there is only one major brewery left in Merrie England (that is fucking pathetic, btw) – that “efficiency” does not help anyone; it just results in less interesting beer, many fewer jobs, and a very small number of golf-playing capitalists.

komarov@#6:

But how is the market “more efficient”? I don’t get this one. What does efficiency mean for the market?

I am sorry; I should have clearly delimited that “more efficient” is a lie. It is, in fact, one of the foundational lies of capitalism.

It goes like this: a market is more “efficient” when redundancies are removed, because redundancy costs money. So if Merrie England has 500 breweries that each cost $5,000,000 apiece, there’s all that infrastructure going to waste! We could shut them all down and build one brewery that needs one giant fermenter large enough for 500 breweries and – sure, it’s a $25,000,000 mega-brewery but we no longer need $250,000,000 worth of breweries! Now watch the little birdie–> In principle that means that mega-brewery could sell its beer for, let’s say, 1/75 of the cost! Beer would be cheaper than water! People would be getting paid to drink the beer!

That never happens, because the capitalists pocket the “efficiency” and sometimes, once they have a monopoly, they raise prices. Then, it’s time for a round of golf and some Budweiser from America!

If your capitalist running dog apologists are American, they’ll say “competition is good!” and then what you wind up with is 2 mega-breweries with plants that cost $25,000,000. Let’s call them AT&T Beer and Verizon Beer. The capitalists will then tell you that the competition keeps prices down! But that’s obviously a lie since we’ve already established that the redundancy squeezed out of the system would price free-market beer at 1/75 or so of what it cost when there were 500 breweries! What happened?! Simple: the two mega-breweries realize that they can make completely awful beer, buy a congressman and pass taxes on imported Badgerian Black Brew (which is great!) to keep it out of the market (#sad) and – even though beer ought to now cost 1/25 of what it used to cost thanks to the reduction in redundancy, you get: a) shit beer, b) twice as many rich capitalists, c) the capitalists can afford to buy expensive Badgerian Black Brew to drink while they have another round of golf!

In the same way as the bacteria eating my brain would be, yes.

I am going to score that as a solid “no”

Here’s another example: remember when they told you that making CDs was much less expensive than vinyl records? That was true. Records were bigger, harder to ship, more delicate, harder to produce, etc. Then remember how they told you that CDs cost 1/10 what it cost to produce vinyl records?

When CDs came out, the cost of music went up!

Clearly, free market economics did not apply to the price of CDs. What happened was the music publishers pocketed more profits, and made more money, and played more golf!

Fortunately, the music consumers of the world figured out a way to thoroughly fuck them back, and now they can’t afford to golf, any more. #sad.

By the way: all I know about economics is what I’ve managed to glean from a couple of economics text books I slogged through. It appears that economics has a lot of theories about what should happen when various changes happen to markets. What should happen is generally “not what actually happens” so – unfairly, I am sure – I think of economics as a field that mostly exists to explain why markets did the wrong thing (“market failure”) and it wasn’t the economists that were wrong, at all.

Ieva Skrebele@#4:

The meaning of Latvian word “prihvatizēt” is “to use the privatization process in order to seize state assets.”

I love that so much.

The Latvian word also sounds an awful lot like “Privateer” in English. Basically thugs given State approval to engage in piracy.

Re #9/#10:

Well, the “Bullshit” was clear enough, but in the context “efficiency” looked more like a marketing buzzword than a fixed definition, which was what I expected hearing the word. That the term is then used to lie, cheat and steal is probably par for the course given the topic. Thanks for clearing it up!

—

Quite the opposite, I’d be fasicnated by the bacteria and capitalists alike, for essentially the same reasons. Neither may seem curable, but before I succumb to either I might as well indulge my idle curiosity.

—

I can’t judge anyone too harshly for that, having worked out quite a few mathematical models to which the real world then refused to conform. Reality failure can so frustrating…

Yes, me too. I find languages and words fascinating, whenever I learn a new language, I discover so many fun words and phrases that express shades of meanings nonexistent in any of the languages I had known previously. The joy of being a polyglot!

I’ll give another example. In Latvian there’s a word “strādāt” (meaning: to work). In Russian there’s a word “страдать” (spelled with English letters: stradat’, meaning: to suffer). Both words are pronounced slightly differently, but they are quite similar. Before retiring, whenever using the word “to work” in a Latvian sentence, my mother usually instead pronounced the word in the Russian way. For example Latvian sentence “es eju strādāt” means “I go to work.” But it was also possible to say “es eju страдать” (just pronounce the last word in the Russian way) and then you get a sentence that means “I go to work to suffer,” the last word in that sentence would simultaneously mean “to work” and “to suffer.” When saying in Latvian “I go to work in order to further enrich greedy capitalists,” this sentence could gain a whole new meaning if you just chose to pronounce one word slightly differently: “I go to suffer in order to further enrich greedy capitalists.” I’d say that for most people the second version is truer.

The things bilingual people do with their languages sometimes are really fun.

No, it’s not 1/75, that’s not how you calculate this. The mega-brewery has reduced one of the costs (namely: cost of equipment used for making beer), but many other costs remain constant (for example: cereal grains still cost the same). Sure, often capitalists don’t reduce prices, because they want more profit and they have a monopoly. But occasionally they do reduce the prices somewhat. For example, in Latvia we have two mega-breweries and about a dozen very small breweries. Beer produced by mega-breweries actually is cheaper than the one produced by the small companies. Personally, I’m no beer expert, but I have heard my friends telling me that the beer from the smaller companies is significantly tastier though.

Well, occasionally I also get this impression, but I don’t think it’s that simple. For example, let’s look at the topic of competition. You said: “The capitalists will then tell you that the competition keeps prices down! But that’s obviously a lie.” It’s not a lie. When you really have competition, it does keep the prices down. In those cases that you mentioned as a proof that economists are wrong, there was no competition, instead there was a monopoly or an oligopoly. Your example of AT&T Beer and Verizon Beer describes an oligopoly. And economists actually say that in situations of limited competition prices are supposed to go up. Which is what happened in your example. Economist theories also factor in branding and marketing. For example, how comes that iPhones are so expensive despite all the competition from cheap Chinese alternatives? It’s because Apple marketing team has managed to convince phone owners that an iPhone is worth paying for so much even though some Chinese made smartphone has all the same functions and costs significantly less. Competition works significally better with non branded products. For example, potatoes sold by farmer John are pretty much indistinguishable from potatoes sold by his neighbor farmers Bob and Donald and Fred. The fact that there’s competition between John, Bob, Donald and Fred keeps the prices of potatoes down.

There’s definitely such a thing as incorrect economic theories. After all, economics is a highly political field; some people are pushing some theories in order to promote certain political goals. Sometimes economists simply make mistakes or fail to take into account some factor (after all, there are countless factors that influence what happens in the markets). But it is unfair to think of economics as a field that mostly exists to explain why markets did the wrong thing. By the way, personally I find economics pretty interesting. Granted, I didn’t have a choice, I simply had to learn the basics, because I had to regularly debate about economics in debate tournaments.

Your discussion of the relationship between so-called efficiency and gambling is apt.

Back in the day when I used to play cards for lunch money I pondered this enigma. If I was able to make a better than even money bet, why not bet all I had on it? Obviously, if I lost the bet I was out of the game, at least temporarily. I never solved the problem myself, but later learned about what is called the Kelley criterion. (Bernoulli had also solved the problem in a different form centuries ago.) The key is to focus on return on investment over time. By being prudent and not betting everything you can maximize your expected return on investment. You have to take your stake into account.

But the modern concept of economic efficiency, as far as I can tell, is marginalistic. That is, it ignores the size of your stake. If you are prudent and take your stake into account, you can lose out to those who take on too much risk or who have a larger stake than you and can take on more risk. If your publicly traded company is holding cash (or the equivalent) back in order to manage risk and maximize return, it could, in theory, be making more money at the moment, and is vulnerable to asset stripping by those who are willing to take on more risk, or are able to pass the risk along to others, or who have more money (a larger stake).

How does Badgerian Black Brew compare to Purple Moose (highly recommended also & brewed by my brother-in-law – https://purplemoose.co.uk)?

@ 10 Marcus

I think of economics as a field that mostly exists to explain why markets did the wrong thing (“market failure”) and it wasn’t the economists that were wrong, at all

I have long had the feeling that much of economics was a branch of fantasy writing, possibly under the influence of drugs. Hey, it worked for Colridge.

I once had an academic economist assure me that a monopoly environment was the best environment in which to foster innovation. And he could prove it! This was in the early 1990’s as Silicon Valley was exploding.

The first time I heard about Utility Theory, I thought it was a joke. Well it was but the economists never caught on for a long time.Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking Fast and Slow mentions that academic economists know that Utility Theory is not valid but it is still taught. It’s like a university chemistry department teaching about phlogiston as a serious theory.

On the other hand, I have seen at least one paper that suggests economists do not use the term “theory” in the same way as any other science discipline does.

This morning, I had a bowel movement that was probably worth more than Donald Trump

Constipation again, eh? Try prunes.

13 komarov

I can’t judge anyone too harshly for that, having worked out quite a few mathematical models to which the real world then refused to conform.

The problem with many classical economists is that when the model fails to map onto reality they tend to assert the model is valid and the reality is wrong. See Marcus’ mention of “market failure”. There are a lot of market failures.

The IMF with its austerity programs is a perfect example. Some economic theory, probably from those idiots in the Chicago School, “know” austerity programs will restore the economy. So far it has not worked very well over the last 40 or 50 years, (Greece is the current most notable victim ) but the theory is right! Next time it will work!

I cannot remember what economic melt down it was, but the IMF was telling everyone to reduce expenditures (code for reducing any services to the poor,and often the middle class, privatize everything that can be flogged and raise prices on things like school fees).

Notably Malaysia gave them the finger, called in some markers from some other Islamic states (probably Saudi Arabia and the UAE but I am not sure) and was in decent economic health a few years before any of the IMF victims were even starting to recover. On the other hand, Argentina followed the orthodox IMF approach and was a basket case for years.

As you may have guessed I don’t have a lot of respect for classical economic theory. I do think that economists have developed some useful concepts and, in some cases, some extremely useful tools that I am happy to use. But then, some remarkable advances in chemistry were made using the phlogiston theory.

Marcus, I think your explanation of margin call is a bit off. Let me try:

You want to buy 10 Diderot encyclopedias for $1,000 each, and plan to get busy with your cutting mat. You only have $1,000, so you borrow $9,000 and use the encyclopedias as collateral. A week later, the same encyclopedia can be bought for $800 on eBay. Your collateral is now smaller than what the bank would want it to be, and they notice this, so they call you and tell you to repay $1,800, to bring your loan back to 90% of the value of the collateral. That’s the margin call. If you have the cash, all is fine, but if you don’t, the banker grabs your Bridgeport mill from your workshop and sells it to raise the cash. They don’t care to get a good price on it, just to cover their $1,800, so they sell it for whatever they can get for it at the moment and you get screwed badly. And you needed the mill to make the frames for the Diderot illustrations, so you’re doubly-screwed.

Forgot to say: the point of the margin call is not that you have to repay the loan when it’s due; but that the lender can demand that you repay part of your loan at any time, if the value of the collateral decreases and no longer covers the loan. When this happens with securities, the same bank often lends you the money and holds the securities for you, so they can just help themselves to whatever they can sell from your trading account — even to things that offset the risks of other stuff you own. They don’t care; they’ll sell the plywood sheets off your windows a day before the hurricane, if it raises the money they want.

cvoinescu@#20:

Your example of a margin call is more accurate than mine; I over-simplified a bit too much. Part of the problem is that the term “margin” is slangified so its meaning can shift slightly, but the main problem is that I took a shortcut and didn’t explain that loans and collateralization are contracts and (except where regulated, like a mortgage loan) the devil is in the detail of the terms. You’re right that, if I borrowed and agreed that the lender could demand repayment at any time if the collateral went under water, then things would play themselves out as you describe. Except you left out the part about how they’d dig up your grandma’s corpse and sell it to lab supply vendors if that was some way they could raise the money out of your assets. “What is a kidney worth these days, Bob?”

Margin calls can look a lot like something out of an early Guy Ritchie movie, yep. I knew a guy who had a big house in Seattle that was bought with a bunch of Microsoft shares as collateral. And … I don’t even need to tell the rest of that story.

Sunday Afternoon@#16:

How does Badgerian Black Brew compare to Purple Moose (highly recommended also & brewed by my brother-in-law

Since Badgerian Black is entirely fictional, it’s got lower calories for sure! But it probably doesn’t taste as good. Purple Moose sounds pretty nice!*

(* Mynd you, møøse bites Kan be pretti nasti)

I wonder what shade your father would turn if he saw this destruction:

Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=187&v=SdxEF51kY_4

The destruction I refer to is shown at about 2:50, but watch it all, I assure you it’s well worth it.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/13/beer-brewing-belgian-monks-accuse-retailer-ethical-breach-westvleteren

Patric Slattery@#24:

OMG no WTF!!

@Patrick Slattery #24:

I saw that exhibition at Holyrood House when it visited Edinburgh – it was fascinating & extraordinary. I didn’t realize that they had cut up a book to make it possible…

It also happens when markets open up. Eastern germany still has not really recovered from the gutting it got when capitalists rushed in after the unification and tore apart anything with value.

There are people that make me want a Ethicshammer of Bashing +5 … .

Is monopoly good for innovation? Yes and no.

In biology, most mutations are deleterious. People are fairly smart, so human innovation has a better chance of being successful, but even so, most new ideas don’t make it. To innovate you have to be able to take on the risk. Monopolies can do that. But that does not mean that they do. Often the reason for innovation is to get a competitive advantage. Monopolies don’t need to do that, so why bother?

The practical way to foster innovation is to grant the innovators monopolies on their innovations for a limited time, i.e., grant patents and copyrights. The current system is flawed, but the basic idea is right. Without monopolies or market power competition drives profits to zero over time. We do want profits to go to zero over time, but not too quickly.

Well, I haven’t even struggled through a couple of textbooks, but the impression I’ve got is that there was a brief period in the mid-20th century where Keynes and his ilk did actually manage to put economics on a sound empirical footing, with a great deal of success… Unfortunately this was not advantageous to capitalists, so over the next few decades they encouraged everybody to forget all of that and go back to the classical economic ideas of the 18th century, which suited them much better. So now Keynsianism is generally regarded as discredited, but nobody can really tell you why.

This is also why we mostly don’t talk about “political economy” any more.

Austerity programs are just an example of political goals determining economic policies. When a country has accumulated so much debt that they cannot possibly pay it back and they face a financial crisis, one of the options is to default and just not pay their debts at all. But that would result in billionaires losing money (after all, it’s the rich guys who have lent money to countries like Greece). You cannot allow that to happen. Therefore austerity measures are pushed as an alternative to defaulting. It doesn’t matter if schools and hospitals are closed, the main thing is that billionaires earn a profit. Everybody knows that austerity measures do not work. They are pushed not because they work, but because that’s what capitalists want. In order to maximize their profits, capitalists need certain economic policies. In order to force voters to accept those policies, they just invent convenient economic theories.

jrkrideau@#17:

I once had an academic economist assure me that a monopoly environment was the best environment in which to foster innovation. And he could prove it! This was in the early 1990’s as Silicon Valley was exploding.

The first time I heard about Utility Theory, I thought it was a joke. Well it was but the economists never caught on for a long time.Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking Fast and Slow mentions that academic economists know that Utility Theory is not valid but it is still taught. It’s like a university chemistry department teaching about phlogiston as a serious theory.

It’s interesting that they know a theory is bogus but keep talking about it. I suppose it’s “pop economics.”

Gah, that just causes us things like Malcolm Gladwell, who appears to have made an interesting career out of pointing out the economists are wrong a lot. I wish I could write a best-seller about water being wet.

Bill Spight@#29:

To innovate you have to be able to take on the risk. Monopolies can do that. But that does not mean that they do. Often the reason for innovation is to get a competitive advantage. Monopolies don’t need to do that, so why bother?

The tradeoffs around monopolies are something that makes my head hurt. Can we agree “it’s complicated” and stop there?

For example, saying that competition has produced wonderful innovations in smart phones – that’s true. But have those wonderful innovations justified their cost? Would we be better off if we had the equivalent of “old” iPhone 5s that cost $25 and were available to poor people worldwide, instead if iPhone X that cost $1000? I don’t know. I’m skeptical as hell about utilitarianism, too, so I’m not going to claim there’s some way we can reason about the utility and social benefits of this or that, because as far as I can see it just looks mighty hand-wavey.

Ieva Skrebele@#31:

Austerity programs are just an example of political goals determining economic policies.

I think it’s actually an advanced case of “regulatory capture.” Wall Street owns a government and uses it to push a political agenda that protects Wall Street’s investments. For that matter, Wall Street owns an army, too…

Dunc@#30:

Well, I haven’t even struggled through a couple of textbooks, but the impression I’ve got is that there was a brief period in the mid-20th century where Keynes and his ilk did actually manage to put economics on a sound empirical footing, with a great deal of success… Unfortunately this was not advantageous to capitalists, so over the next few decades they encouraged everybody to forget all of that and go back to the classical economic ideas of the 18th century, which suited them much better. So now Keynsianism is generally regarded as discredited, but nobody can really tell you why.

That nicely summarizes my view, too. Thank you for the confirmation bias.

I got dug into the beginning of Capital back in 2009 and it’s … interesting. Keynes was trying to nail down some of the things that Marx approaches dialectically. (Marx’ dialectics is a really interesting thing but they make my head hurt) So the arguments against Keynes appear to be that many of the underpinnings of economics as a whole are squishy. In other words, to destroy Keynes, economists blew up their own epistemology. It hearkens back to Popkin’s History of Skepticism in which the Catholics and Protestants blew up eachother’s epistemology in order to win their disagreement, thereby both losing.

I have not written about it, but … I watched a lecture by Milton Friedman the other day. Fascinating stuff. What I learned was that Friedman was an asshole. Here was a guy who started out poor, got a scholarship to a big university, made a name for himself, and turned around and started crapping all over the social safety net and egalitarianism. I need to go back, take some valium, and re-watch that.

This is also why we mostly don’t talk about “political economy” any more.

Right. It’d be like talking about “applied social science.”

Marcus Ranum@#33

Tradeoffs around monopolies are complicated? You bet. :) Amazon has blazed a new path for monopolies by not making a profit and thus becoming a monopoly. Uber’s game plan is to become a monopoly; its best bet is to pass on a lot of cost and risk to drivers. I avoid patronizing both of them.

Anti-trust law is a blunt instrument, but the best tool to rein in monopolies that we have, IMO. Unfortunately, in the US it has been defanged, with the idea that monopolies are OK if they keep prices down. OC, that last is an unprovable assertion. It’s not the consumers that need protection, it’s the smaller businesses. Without small businesses and unions, where is our middle class?

As for utilitarianism, it is reductionistic. People do have non-transitive preferences, because value is multi-dimensional. Economists “save” utilitarianism, in a way, by making it purely personal. If they allow comparisons across individuals, a vicious sadist could claim that his torture murders are good, because he derives much more pleasure from them than his victims pain and society’s benefits from executing him. But if you accept average utilities, this problem goes away, as does transitivity on the large scale. The early battle cry of utilitarianism was “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Surely that implies utility averaging. In socio-economic terms the greatest number are the lower classes.

To Bill Spight

I prefer Rawls’ “Veil Of Ignorance” standard as my accumulation function for utilitarian analysis. It’s squishy, but it points you in the right direction for the sort of the analysis that should be made.

The tradeoffs around monopolies are something that makes my head hurt. Can we agree “it’s complicated” and stop there?

A friend of mine told me that he was taught that four competitors (his example: supermarkets) would naturally set prices to a high level, and competition would not work to bring them down, even without deliberate price fixing. Take that with a grain of salt, because citation very much needed, but it would mean that even if you added Comcast Beer and Sprint Beer, you’d still be drinking expensive yellow water.

For example, saying that competition has produced wonderful innovations in smart phones – that’s true. But have those wonderful innovations justified their cost?

The cost is absolutely not justified. We know how to make a cheap, good phone, but we don’t, because there’s much less profit in it, and it would eat into the sales of $500+ phones. They actually do make cheaper, decent phones for the less extravagantly rich countries (e.g. China, Eastern Europe, South America), but they intentionally don’t sell those models in the US or Western Europe.

But it’s not competition alone that has enabled the wonderful innovations. A lot of them are the fruits of state-sponsored research — obviously the Internet, but also less obvious things such as the radio protocols, some forms of encryption, algorithms, and even the computer to begin with. Companies are good at turning these into money-making products, but universities are much better at fundamental research. Or, to put it differently, companies turn knowledge and money into more money, and research universities turn knowledge and money into more knowledge. Yet we sabotage education and research whenever we can, and treat teachers and most scientists like shit, but we give lavishly to companies and their bosses and owners.

Sometimes competition does work to reduce prices, other times it does not. This depends on a multitude of factors:

– How easy it is to compare the prices? For online shops it takes only a couple of mouse clicks, for brick and mortar stores you don’t know how much the competitors charge until you go to a different store and check.

– How much time and effort it takes to buy from another source? For example, most people buy their groceries in the shop that’s closest to their home, not going to a more distant shop even if their prices are better.

– Do marketers manage to successfully create the false impression that the more expensive brand name product is somehow better and more unique compared to cheaper alternatives?

– Do companies employ any tools to minimize purchasers’ choices? For example, theoretically there is some competition in the e-book market. There’s Amazon Kindle, Kobo Aura, Barnes & Noble Nook and a bunch of other stores selling e-readers and e-books. In reality, if you have bought a Kindle, you aren’t going to be getting your e-books from Barnes & Noble. Personally, I really hate this kind of crap. Which is why instead I’m using an Onyx Boox e-reader and I get my e-books wherever the hell I want.

– How easy it is to switch to a competitor’s product? Have you signed any contracts saying that you are obliged to stick with this seller for some period of time? Does switching to a competitor requires installing new wires in your home?

I can think of many examples where competition managed to significantly reduce prices. But I also know examples where it didn’t work.

My current phone is Samsung Galaxy S4. This model costs 150 € brand new and unlocked in German online shops. If you are OK with a used or a refurbished phone, the price for this model drops significantly more. If 150 € is too much for you, you can also get brand new and unlocked phones for as little as 15 €, also in German online shops. Alcatel, LG, Nokia, Samsung models without touch screen and with physical buttons (still remember those?) are available in German shops. German shops offer a lot of models in the 15 to 25 € price range. You don’t like physical buttons and you want a touch screen model? Well, in German online shops, those start at about 50 € (brand new and unlocked). And it’s not just German shops that offer countless options for cheap phones. It’s the same with British online shops. I’d say the claim that nobody sells cheap phone models in Western Europe is false.

There’s also a problem with the word “intentionally.” Sellers will offer literally anything as long as there’s a market for it and as long as they can make a profit. American sellers would be happy to sell even $10 phones if only Americans were willing to buy them. If sellers aren’t offering some product for sale in the U.S., then that’s only because there’s no demand for it (namely: Americans, in general, don’t want to buy the product).

Besides, even if no local sellers offered cheap phones for sale, you could just buy one online from international sellers. A person working in a Chinese online shop will be more than happy to simply ship the phone to your U.S. address.

Personally, I don’t mind that Apple is selling overpriced iPhones. I just don’t care about those, as I don’t intend to buy one. It’s not like I don’t have options for good quality cheap phones. In fact, there are literally hundreds of cheap and pretty good models I can choose from.

If being unlocked is not a major goal, there are a lot of cheap phones being sold by the majors.