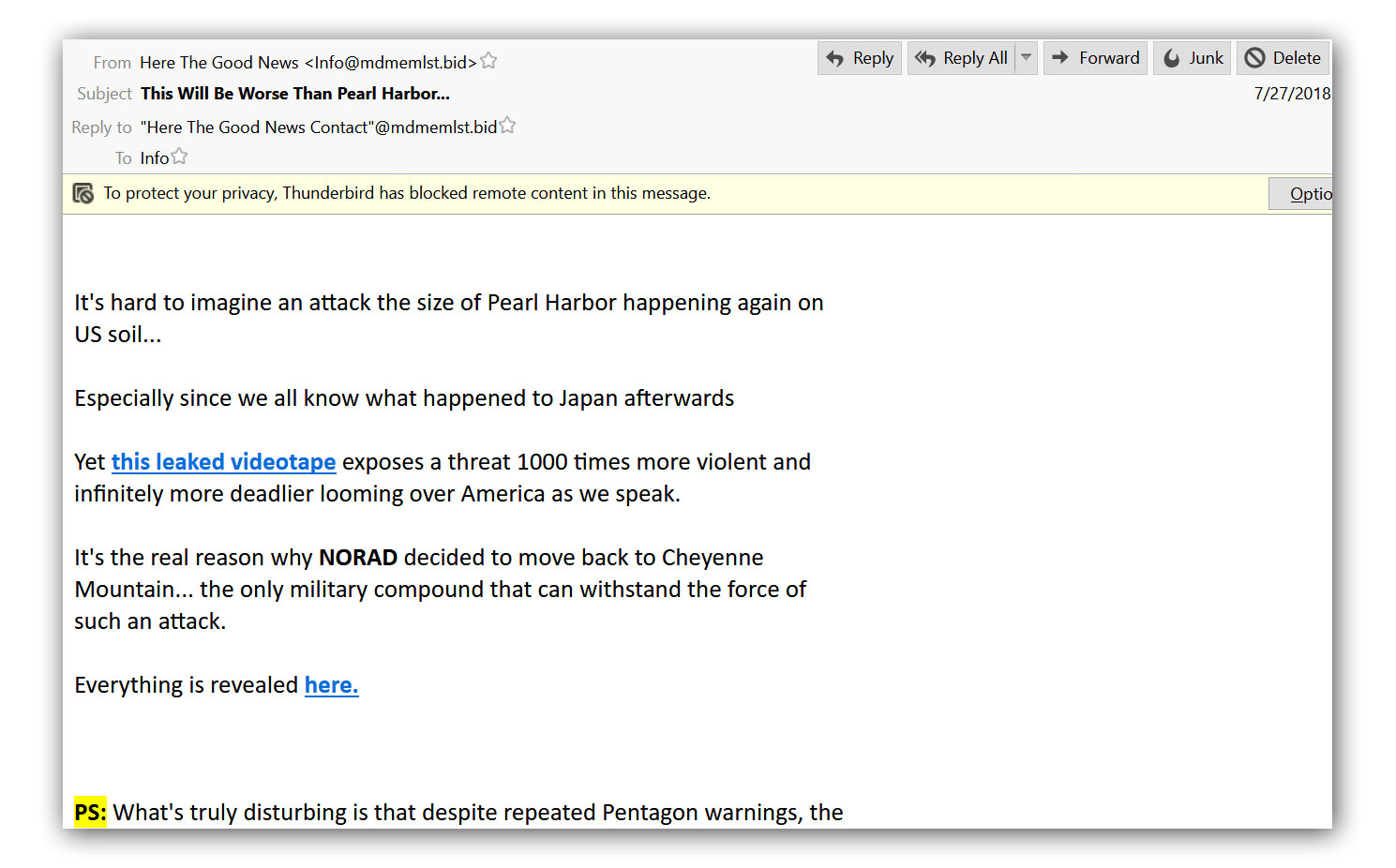

The people who read and believe this stuff are the foundation of American anti-intellectualism. And they vote:

I never expected my spam-box to become a source of material, but it slowly sunk in to me that this is important “cultural context.”

Americans have always been ‘fraidy-cats that you can sell tactical gewgaws to, when you need to raise money. This sort of blatant appeal is the same message that motivates Jim Bakker (and Jim Jones’ for that matter) base to act: mysterious abstract fear or something-or-other undefined.

For one thing, Pearl Harbor was a strategic failure and didn’t really do that much damage. Sure, it shocked the US imperium into action but in terms of military significance, it wasn’t that big a deal and it was only a surprise because the US was complacent, ignored its intelligence service and diplomats, and responded incompetently. So “bigger than Pearl Harbor” means, what, exactly?

I used to have a loose friend (a “loose friend” is someone who thinks you’re their friend but you consider them more of an acquaintance, keep in touch with them periodically, but don’t go much out of your way to spend any time with) who used to believe all the ‘EMP bomb from North Korea will throw us back into the dark ages!” nonsense. At first, I tried to explain that atmospheric EMP tests had been run in the 50s and 60s and that he should read up on HARDTACK ORANGE and maybe he’d notice that it hadn’t thrown civilization back to the dark ages, except for in San Francisco. I tried to explain to him that nuclear forensics includes some very clever and effective techniques (I only know the declassified ones) and that there really is no such thing as an “anonymous nuclear air-burst”) after a few back-and-forth exchanges about the topic, he’d shut up about it for a few months then suddenly he’d come right back with more of the same. I eventually realized that he wasn’t listening to a damn thing I was saying, so I “went meta-” and said:

“T. –

I realized that we’ve discussed this before and it finally dawned on me that you simply are not listening. I keep trying to explain facts and prior knowledge, and you keep coming back with this strongly-held opinion that this horrible thing is going to happen any day now. For over a decade. I’m tired of trying to explain it to you, so I think it’s best if you no longer consider me part of your circle of friends, and I add your email address to my spam filters, and we don’t have this kind of discussion any more.”

And that was that. Why do we allow these time-wasters to come traipsing into our lives and create these pointless discussions? I realized, in that moment, that he was basically a spammer to me – and his opinion mattered about as much.

I’m back on haitus from Facebook and Twitter (just in time for the internet advertising bubble to begin to wobble a bit!) because another ‘friend’ managed to make a comment which showed up on his time-line which sucked in a bunch of mormon reactionaries, ex-military, and other flavors of time-wasters. After thinking about it for a bit I realized that the only way to prevent that from happening was to start dropping any of my ‘friends’ who ever did that to me. The time before, when I went on haitus, it was the same thing – I dropped everyone who posted a kid picture, a sports picture, or anything religious. It turned out to be a good exercise; I discovered that I only valued a small handful of friends and they weren’t why I was on Facebook in the first place. Buh-bye!

This just got me thinking. For me to fear something, “mysterious, abstract and undefined” simply won’t work. I need to be able to clearly imagine the possible bad outcome in order to fear it. And whether I can imagine something largely depends on whether I have experienced anything similar in past. For example, when I see a hot pot on the oven, I’m reluctant to touch it with my right hand (I always use my left hand for anything even remotely risky, I even hold my computer mouse my left hand, because I fear repetitive strain injury). About 10 years ago I burned my right hand with some boiling strawberry syrup, and not being able to draw anything or even hold a pencil for some days really sucked. Thus I learned to really fear injuring my dominant hand. I can also fear something if it has never happened with me, yet I can clearly imagine the unpleasant experience, because it can be easily extrapolated based on what unpleasant things I have already experienced. For example, I have never experienced severe sexual abuse, yet I’m still capable of fearing it, because I can use my various other past experiences of different forms of abuse in order to extrapolate how sexual abuse could feel. In my life I have also experienced cases where repeatedly experiencing something that used to scare me resulted in me completely losing that fear. For example, as a child I used to fear people getting angry in my presence and starting to yell at me. At some point I just stopped caring—somebody else’s anger management problem shouldn’t even concern me. Another example: as a teenager I feared speaking in public. After being forced to do so for a couple of times, I got used to it and lost that fear. The point is—what I fear is closely tied to 1) my past experiences, and 2) my ability to clearly imagine the dreaded scenario. Something “mysterious, abstract and undefined” simply doesn’t work on me.

Now that I hopefully managed to explain the principle, on to the real scary problems (like nuclear disasters, for example). I know how pain feels like, so I’m capable of fearing a nuclear disaster, because it would really hurt for humans who are exposed to the radiation. But that’s not enough. I also need to be able to fully imagine the scary scenario, exactly how it could happen. The exact thing that could go wrong, what would happen, how exactly. And the scenario must be plausible and reasonable and at least somewhat likely to happen. I must be able to imagine the whole chain of events that leads to the disaster. Only then it will feel scary for me. If somebody simply tells me, for example, “nanoparticles are dangerous; they will kill us all,” that’s not enough to make me scared. I need a clear and plausible and reasonable scenario for how exactly it would happen. If I don’t understand what could go wrong and how, I cannot imagine the scary event, and I cannot feel afraid.

I deal with this problem differently. For example, I have a very close friend (he’s been my friend for years and still is) who once started talking about how “the human eye is too complex, it couldn’t have evolved” (yep, that crap, although, being agnostic, he at least skipped the “therefore God created us” part). The two of us were hanging out in a beach that day, so I tried my best to explain how the eye actually evolved (it’s so damn hard to explain the intricacies of evolution when I’m away from my computer and reference books, and I have to rely exclusively on my memory). Anyway, I failed to convince him (all I could do was tell him to read a book by Donald Prothero that I had read on the subject). That was the last time we had this discussion, it hadn’t gone anywhere, so we didn’t repeat it. And we stayed friends who simply didn’t discuss evolution ever again. If I don’t enjoy talking with some friend about some topic, I can talk with this person about other topics. We can just agree to disagree, and that settles the problem. It’s not obligatory for me to ensure that all my friends believe exactly the same things I do.

As for spam e-mails. If a friend sends me an e-mail with some boring question, I won’t answer it (or I’ll type a single sentence answer if I must). It’s not hard to simply ignore a question that I perceive as boring and don’t want to waste my time typing an answer to. On the other hand, if a complete stranger asks me something interesting, I will answer. Whether I choose to have some discussion depends on how interesting for me are the topic and contents of that discussion, rather than on who the conversation partner is. Everybody is welcome to ask me questions or approach me with conversations, and I’ll decide which ones I want to answer based on what seems interesting for me. If I end up frequently communicating with some person because I perceive our discussions as interesting, then we are likely to become friends over time. If, on the other hand, somebody who used to be my friend starts to bore me, then we’ll just drift apart by communicating less and less frequently. It seems like I look at this question from a different angle. I never feel obliged or pressured to do something I don’t want to do just because the person who proposed this activity has the status of being my friend. The question I ask is “do I enjoy this experience (this discussion, this dinner, whatever)?” If I find out that I frequently enjoy the experiences I have together with some person, then that settles the question that I do want to have more similar experiences with them in the future, and that I might as well call this person a friend.

Yep, that sounds about right. This is why I have never made a Facebook account in the first place. This and a few more reasons.

There is a Japanese writer, Marie Kondo, who has achieved a level of international fame through a series of books describing how to reduce the amount of clutter in one’s home; at its heart, her advice reduces to evaluating each item and asking if it brings joy into one’s life. It might seem cowardly or solipsistic but perhaps we should be asking the same of the people we let into our lives, especially our online ones. I shut down my Facebook and Twitter accounts a few months ago because, although they were useful condos for staying in touch with close friends and family members, and ways of making connections with interesting people I would never have otherwise come in contact with, the mental price was just too high to pay in the long run.