Imagine you’re a graduate student in American History and you write a thesis that’s so good, so striking, and so timely that it’s deservedly a best-seller: 200,000 copies. As Ray Wylie Hubbard says, “careers have been built on less.”

Richard Hofstadter

For Richard Hofstadter, that best-seller was just the beginning of a long string of brilliant, analytical history.

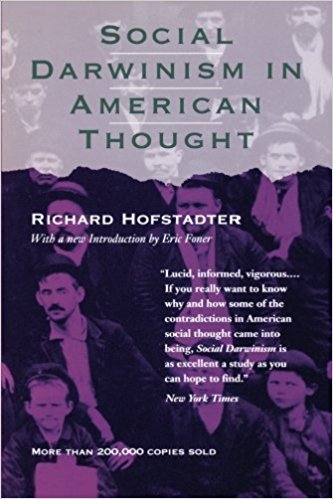

That thesis was published as Social Darwinism in American Thought [amzn] and it’s been in print since 1944 – also pretty good for a thesis. What most of us atheist/skeptics don’t understand is that Hofstadter pulled together and explained the events and the process whereby Darwin’s theory fused with American laissez-faire industrial capitalism, and became – for many – what amounts to America’s true religion.

That sounds like a grandiose claim, doesn’t it? It’s understating the case. Anyone who studies the relationship between labor and capital during the industrial revolution, cannot help but come face to face with industrial capitalists like Andrew Carnegie, pushing his “Gospel of Wealth” – and where did those ideas come from?

Hofstadter starts with Herbert Spencer, who began as what today we’d call a “science communicator” with a philosophy of progress that was agnostic yet teleological: we get better as human beings and make better of ourselves because of our desire to transcend; to achieve an adapted, harmonious, state. Spencer’s philosophy was like a fresh petri dish waiting for Darwin’s ideas to percolate into. Christianity was falling apart – it was pretty clear to any thoughtful person by then that the best that could be salvaged from it was that sense of telelogy; Spencer stepped into the gap. Not deliberately, but decisively. As religion has always served the powerful as a justification for the divine right of kings, America’s new industrial elite were eager to find a new justifying paradigm by which to explain their tremendous wealth and power, and to absolve them of any shame they might feel for building that wealth on the backs of laborers that they (to put it bluntly) robbed ruthlessly at every opportunity.

John D. Rockefeller, speaking from an intimate acquaintance with the methods of competition declared in a Sunday-school address:

The growth of a large business is merely a survival of the fittest … The American Beauty Rose can be produced in the splendor and fragrance which bring cheer to its beholder only by sacrificing the early buds which grow up around it. This is not an evil tendency in business. It is merely the working-out of a law of nature and a law of God.

The most prominent of the disciples of Spencer was Andrew Carnegie, who sought out the philosopher, became his intimate friend, and showered him with favors. In his autobiography, Carnegie told how troubled and perplexed he had been over the collapse of Christian theology, until he took the trouble to read Darwin and Spencer.

I remember that light came on as in a flood and all was clear. Not only had I got rid of theology and the supernatural, but I had found the truth of evolution. “All is well since all grows better,” became my motto, my true source of comfort. Man was not created with an instinct for his own degradation, but from the lower he had risen to the higher forms. Nor is there any conceivable end to his march to perfection. His face it turned to the light; he stands in the sun and looks upward.

Perhaps it was comforting, too, to discover that social laws were founded in the immutable principles of the natural order. In an article in the North American Review, which he ranked among the best of his writings, Carnegie emphasized the biological foundations of the law of competition. However much we may object to the seeming harshness of this law, he wrote, “It is here; we cannot evade it; no substitute for it has been found; and while the law may sometimes be hard for the individual it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department.” Even if it might be desirable for civilization to eventually discard its individualistic foundation, such a change is not practicable in our age; it would belong to another “long succeeding sociological stratum,” whereas our duty is with the here and now.

Not ostentatious

Carnegie had founded a personal religion that perfectly justified his rapaciousness and selfishness because it was all going to make everyone better someday after he had enjoyed a life of mansions and luxuries, power, and respect. It clearly never occurred to Carnegie that he might try to elevate the situation of his workers and improve their lives.* Carnegie would have fit right in with today’s libertarian or Randian crowd, the apostles of “I’m all right, Jack, keep your hands offa my stack.”

If you want a grim laugh, you can read about Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth [wik] – a paean to rich people patting themselves on the back by helping those who deserved it; you know, the middle class and those least likely to waste it on drinking and dancing. Carnegie, naturally, felt that ostentatious and luxurious living was inappropriate – so he had a huge mansion on 5th Avenue in New York, a palace named Skibo in Scotland, and, sorry, I can’t keep a straight face anymore. As he felt his death approaching, he reinvented himself as a philanthropist – but only after sheltering enough wealth to gift America with an endless plutocratic line of Carnegie offspring.

Conservatism and Spencer’s philosophy walked hand in hand. The doctrine of selection and the biological apology for laissez faire, preached in Spencer’s formal sociological writings and in a series of shorter essays, satisfied the desire of the select for a scientific rationale. Spencer’s plea for absolute freedom of individual enterprise was a large philosophical statement of the constitutional ban upon interference with liberty and property without due process of law. Spencer was advancing within a cosmic framework the same general political philosophy which under the Supreme Court’s exegesis of the Fourteenth Amendment served to brilliantly to turn back the tide of state reform.

See what I mean about how effortlessly and clearly Hofstadter ties all this together? These extracts, I have pulled from a pair of pages; the entire book – all 200+ pages – is full of comparable insights. You can open the book to practically any page and encounter something that will increase your understanding of America. Usually it will make you more disgusted with America. He’s cool and unsparing:

The social views of Spencer’s popularizers were likewise conservative. Youmans took time from his promotion of science to attack the eight-hour strikers in 1872. Labor, he urged in characteristic Spencerian vein, must “accept the spirit of civilization, which is pacific, constructive, controlled by reason, and slowly ameliorating and progressive. Coercive and violent measures which aim at great and sudden advancement are sure to prove illusory.” He suggested that, if people were taught the elements of political economy and social science in the course of their education, such mistakes might be avoided.

The coercive and violent measures Youmans was referring to were the strikers who shut down and fortified factories to negotiate for better working conditions – the coercive and violent measures of the heavily armed Pinkertons’ strike-breakers were, one supposes, teleology in action. It was into this environment that Marx’ writings fell, and that helps us all understand why America developed such a violent aversion to Marxism that it violently struggled to eradicate it world-wide. The proto-social Darwinists of America were fully engaged as excuse-makers for the ruthless capitalists, and, as they justified their extravagances they had to implicitly treat the workers and less fortunate as lesser beings. It all made sense.

I’m sorry to say, but when theists accuse atheists of promoting social darwinism and its many evils, they’re pretty much right. The response we should make is not to deny it but rather to point out, “Spencerian social darwinism was a substitute for religion as a way of justifying unrestrained power and greed. In that sense, the social darwinists were merely replacing christianity as a system of oppression.” And, besides, we know that their science was bad. [stderr] The social darwinists and eugenicists had cause and effect confused; it was a great big post hoc ergo propter hoc error. It oughtn’t suprise anyone to learn that the most vigorous attacks against Spencer were from the faithful, not atheists – christians didn’t like Spencer’s “The Unknowable” semi- deism, since it wasn’t specific support for their beliefs. Sadly, the christians of the period didn’t have practice arguing against scientism (yet) so they missed the obvious holes where Spencer’s arguments could be attacked.

Hofstadter also makes one of the smoothest literary put-downs I’ve ever encountered:

Although its influence far outstripped its merits, the Spencerian system serves students of the American mind as a fossil specimen from which the intellectual body of the period may be reconstructed.

Oh, snap.

That’s just a bit of the flavor of the first two chapters! Hofstadter goes on to trace how Spencer’s thought wove through American journalism, public intellectualism, and – of course – higher education. The newly evolving “science” of psychology was eager to embrace social darwinian ideas and mingled and metastasized with good old American racism to produce eugenics. These ideas are with us today, unfortunately. Social darwinism, racism, and plain old elitism all rely on post hoc reasoning: certain people don’t do as well as others, it must be because the others are better or there’s something wrong with the people who aren’t doing well. Either way you flip it, it’s the same reasoning and it doesn’t take into account that they may be being held back, or that the other competitor may have an un-natural advantage like having rich or powerful parents.

There was nothing in Darwinism that inevitably made it an apology for competition or force. Kropotkin’s interpretation of Darwinism was as logical as Sumner’s. Ward’s rejection of biology as a source of social principles was no less natural than Spencer’s assumption of a universal dynamic common to biology and society alike. The Christian denial of Darwinian “realism” in social theory was no less natural, as a human reaction, than the harsh logic of the “scientific school.” Darwinism had from the first this dual potentiality; intrinsically it was a neutral instrument, capable of supporting opposite ideologies. How, then, can one account for the ascendancy, until the 1890’s of the rugged individualist’s interpretation of Darwinism?

The answer is that American society saw its own image in the tooth-and-claw version of natural selection, and that its dominant groups were therefore able to dramatize this vision of competition as a thing good in itself. Ruthless business rivalry and unprincipled politics seemed to be justified by the survival philosophy. As long as the dream of personal conquest and individual assertion motivated the middle class, this philosophy seemed tenable, and its critics remained a minority.

This book has been added to my recommended reading list;[stderr] you can now get a copy risk-free thanks to my “you will love this book” guarantee.

This book has been added to my recommended reading list;[stderr] you can now get a copy risk-free thanks to my “you will love this book” guarantee.

Since I first read the book while I was tripping in and out on oxycodone, I read it through twice, to make sure that the part about the lizard-men ruling Wall St was confabulation (it was) and also to take notes.

* Carnegie, ever the capitalist, screwed his workers in myriad tiny ways – a percentage point here and there across the entirety of his business equated to a great deal of money for him and presumably his workers didn’t notice. In fact, naturally, they did: so when they complained, Carnegie brought in the Pinkertons to break their heads. I will write more about Carnegie some other time, but I’ll have to take some anti-regurgitants first.

Well, many Christians ended up endorsing laissez-faire capitalism with the Prosperity Gospel movement, which I believe heavily influenced today’s Christian Right and its enthusiastic endorsement of capitalism. There was also the rival Social Goapel movement, heavily critical of capitalism, but it didn’t end up having as much long-term influence.

One irony I think is that when Hofstadter wrote his thesis, Social Darwinism had somewhat fallen out of fashion in the US, along with unregulated capitalism. In the late 20th century, as laissez-faire capitalism became more fashionable again, social Darwinism also started to reappear.

Straight onto my reading list. Thanks!

Caine@#2:

Straight onto my reading list.

It’ll keep your pipes from freezing!

No, wait, that’s Jim Bakker’s survival ‘food’…

Marcus:

Talk about pipe blockage! I’ll be reading this right after Jan Bondeson’s Rivals of the Ripper: Unsolved Murders of Women in Late Victorian London, which I just started.

springa73@#1:

Well, many Christians ended up endorsing laissez-faire capitalism with the Prosperity Gospel movement, which I believe heavily influenced today’s Christian Right and its enthusiastic endorsement of capitalism.

Hofstadter died in 1970, the Prosperity Gospel movement already existed, under a different name.

From Wikipedia:

I’d tend to agree with that; the linkage between prosperity theology and Carnegie’s worship of wealth is pretty clear. I started reading some of Carnegie last year and it was pretty bad drivel. Perhaps it’ll merit some review.

Hofstadter wrote:

The predators are running the country, now. The vocabulary is different.

Carnegie emphasized the biological foundations of the law of competition. However much we may object to the seeming harshness of this law, he wrote, “It is here; we cannot evade it; no substitute for it has been found; and while the law may sometimes be hard for the individual it is best for the race, because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department.”

A laissez faire attitude towards economic transactions makes just as much sense as a laissez faire attitude towards murder and assault. Social Darwinists might as well have proposed murder to be legalized. Sure, some people would get killed and the system might be cruel for the individual, but in the long term it would be beneficial for the human species (weak people get killed and don’t pass on their bad genes). Never mind that the plan would fail (it’s not the stronger people who would survive, instead it would be people who have access to guns). In a laissez faire capitalism we have a similar problem — it is not the smartest people who earn most money, it’s just those who are lucky and have the right opportunities.

Regarding the prosperity gospel. I grew up in an atheist bubble and I learned about Christianity mostly from history books. I was extremely surprised when I found out about American prosperity gospel. It seemed contrary to everything I knew about Christianity. Somehow I have always associated Christianity with ideals of poverty and humility. There was Jesus who claimed that it was “easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.” Greed was one the seven deadly sins for Christians, their religion required to turn the other cheek, love your neighbor, give to charity and be a selfless person. Growing up in an atheist bubble, the only Christian person I personally knew was the mother of my childhood friend and she claimed that her religion required renouncing worldly possessions.

Of course I was aware of pope being the exact opposite of poor and plenty of rich kings being officially Christian. Still, all these cases seemed like hypocrisy for me. I saw poverty and charity as the ideals of Christianity and it was simply that rich people failed to conform to these ideals. Consider, for example, the Dominicans and Franciscans, founded by Saint Dominic and Saint Francis, who were committed to owning nothing. These monks were beggars who preached to the poor and cared for the sick and the destitute. Francis of Assisi abandoned his family riches, ate the plainest food, wore simple garments, and owned practically nothing. Somehow I ended up seeing this as the ideal of Christianity: be poor, humble, donate to charity, help the poor, care for the sick and unfortunate.

And then by the time I was about 20 I first heard about American prosperity gospel. For me it seemed absolutely incompatible with the ideals of Christianity.

Ieva Skrebele@#6:

A laissez faire attitude towards economic transactions makes just as much sense as a laissez faire attitude towards murder and assault.

Agreed. I don’t really think it’s that far off for those that quote Hobbes’ war of all against all – they’re proto-survivalists, as far as I can tell.

Social Darwinists might as well have proposed murder to be legalized.

For Carnegie, it was. Many of the industrial capitalists would call upon the national guard, or Pinkertons’ to break strikes – often using military weapons. To give you some of the character of these events:

1) Carnegie negotiates an annual production-based bonus with the mine-workers’ union

2) Carnegie calculates the bonus at Christmas, when steel prices were at their lowest and indexes the bonus to the sale value of the commodity

3) The union complains

4) Carnegie tells them they can quit and go work someplace else

5) The union goes on strike and locks out the steel plant

6) Carnegie brings in 2 gunboats loaded with Pinkertons with Winchester repeating rifles

7) People are killed

8) The bonus is re-negotiated to half of what it should be

9) That’s it

That’s. It. It should be familiar to anyone who watched #NODAPL and rental cops and militarized police attacking civilians with impunity.

it is not the smartest people who earn most money, it’s just those who are lucky and have the right opportunities.

Don’t forget ruthlessness. It’s a matter of opportunity and ruthlessness, more than smarts. That’s a big part of Hofstadter’s underlying argument: the American social darwinists are apologists for and helpmeets to some of the worst people in the society.

From my perspective, I step back and look at the political leadership and see the revolving door: the US is run by and for horrible people like Carnegie. The social darwinists (and to springa73’s point at #1, the propserity gospelists) are justifying the actions of the political and economic elites the same way that religion worked to justify the divine right of kings. It’s the same shit, it’s just a different day.

I was extremely surprised when I found out about American prosperity gospel. It seemed contrary to everything I knew about Christianity.

I’m sure that, as you explored christianity more, you realized that its salient characteristic is “convenient doctrinal flexibility.” (Except for where it’s so inflexible that they kill people over it)

Greed was one the seven deadly sins for Christians, their religion required to turn the other cheek, love your neighbor, give to charity and be a selfless person.

Carnegie and the prosperity gospel preachers basically made greed a virtue. I don’t want to spoiler too much but, naturally, Hofstadter ties it all together with American imperialism, racism, etc. This all plays straight into the “white man’s burden.”

6) Carnegie brings in 2 gunboats loaded with Pinkertons with Winchester repeating rifles

7) People are killed

8) The bonus is re-negotiated to half of what it should be

Oh, crap! My experiences with strikes were a lot more civilized. Here we don’t have them as often as in France, but they occasionally happen. I have fond memories from almost 20 years ago when I got to skip school, because all the teachers were on a strike. It usually happened as following:

1) Workers demand increased wages, they are refused.

2) Workers don’t show up for work for a day.

3) Wages get raised by a tiny amount that is only a fraction of what workers demanded.

4) That’s it.

I’m sure that, as you explored christianity more, you realized that its salient characteristic is “convenient doctrinal flexibility.” (Except for where it’s so inflexible that they kill people over it)

Every religion must have some convenient doctrinal flexibility, otherwise it just cannot survive. Whenever life circumstances of the believers change, so must their religion.

I have to admit that most of what I know about contemporary American Christianity comes from atheist sources (for example, TheThinkingAtheist radio podcast). I just can’t stomach the idea of actually reading Christian crap.

Carnegie and the prosperity gospel preachers basically made greed a virtue.

In my opinion greed is neither a virtue nor a vice. Almost all people are at least somewhat greedy (otherwise the species couldn’t survive). That’s normal. I have a problem with greed only when it goes overboard. For example, when a billionaire refuses to pay Bangladeshi sweatshop workers who are sewing clothes a wage that would at least allow them to avoid starvation, then that’s evil and disgusting. Same goes for American travel bloggers who haggle with impoverished Indian rickshaw drivers over a couple of cents. I find greed extremely disgusting whenever a rich person is attempting to shortchange somebody very poor. However, when nobody gets hurt as a result, I see nothing wrong with desiring nice things. For example, I charge quite a lot for my artworks. Poor people generally don’t commission custom art, so I can assume that my clients can afford my fees (or they can find another artist willing to work for less). Since I’m not hurting anybody, why not charge as much as I can possibly get away with?

Today I finished reading Social Darwinism in American Thought. It certainly was interesting.

I have never read the Bible. Not from cover to cover as one reads books. I have only read some quotes from it (the ones atheist activists love to quote). When I was about 17, I once tried reading the Bible. I started with the first page of the New Testament, and I managed to get through about ten pages or so. I quit, because I just couldn’t bear the bullshit. After every sentence my brain screamed, “Wait, stop! This is wrong, because. . .”

Social Darwinism in American Thought started with an overview of Spencer’s ideas, and while reading that chapter my brain kept screaming, “Wait, stop! This is wrong, because. . .” Spencer’s ideas were just so wrong. Even reading another author’s overview of Spencer’s ideas kept my brain’s bullshit alarm go off after every sentence. I would really dislike reading the original texts of Social Darwinists.

What really ticked me off wasn’t just the fact that some dude pulled bullshit claims out of his ass (after all, countless people have invented incorrect theories for millennia), the real problem was that Social Darwinists’ ideas had harmful real life consequences—many poor people had miserable life quality, some even died just because some rich assholes cooked up a silly theory about why they are so amazing and why they deserve moar money. Reading about topics like Social Darwinism feels like stepping into a pile of shit only to discover that there’s more shit everywhere around me. It’s basically a story about some deeply prejudiced people trying to make their inherent racial and social biases sound science-y. Well, they certainly had plenty of intellectual followers to this day—if you have some stupid idea you want to successfully sell to a broader audience, just pad your writings with some scientific terms, and voilà, the theory you pulled out of your ass now sounds a lot more credible.

Overall, I didn’t enjoy reading this book. For the same obvious reason why I couldn’t enjoy reading, for example, a book about the Holocaust. History books can often be really grim and make me feel like humanity sucks. But this book was certainly interesting and worth reading, though.

And now I’m left to think about the offshoots of these ideas that we still have alive in our current modern world. Oh well, at last I now have a better understanding about where they came from.

Ieva Skrebele@#9:

“Wait, stop! This is wrong, because. . .” Spencer’s ideas were just so wrong. Even reading another author’s overview of Spencer’s ideas kept my brain’s bullshit alarm go off after every sentence. I would really dislike reading the original texts of Social Darwinists.

I have several. When I try to read them I have a similar reaction. I nearly threw a semi-valuable 1st edition of The Passing Of The Great Race against a wall. This shit is unbelievably shitty shit.

the real problem was that Social Darwinists’ ideas had harmful real life consequences—many poor people had miserable life quality, some even died just because some rich assholes cooked up a silly theory about why they are so amazing and why they deserve moar money. Reading about topics like Social Darwinism feels like stepping into a pile of shit only to discover that there’s more shit everywhere around me.

That pretty much explains what the inside of my head is like all the time.

It doesn’t help to see atheo-skeptics like Sam Harris even bother engaging with these theories as if they are worth talking about.

No, you cannot have that all the time. That’s how people get sad and depressed. You must think happy thoughts every now and then—cute, fluffy puppies (or hot, naked, tied up women or pretty sharp knives, whatever you prefer).

Well, that’s why I never emotionally embrace some movement or associate myself with any of them. This way, if Sam Harris starts defending stupid ideas, it doesn’t bother me any more than if Jim Bakker started defending some stupid ideas.