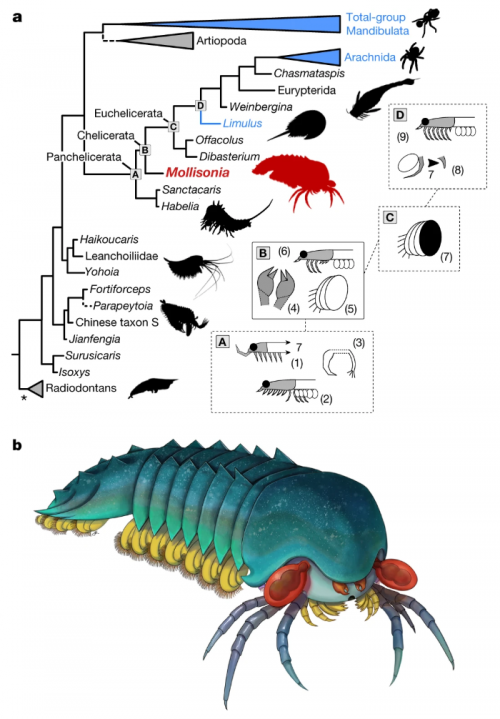

I never heard of the Thylacocephala until I saw this video, and they are bizarre arthropods, now extinct, unfortunately. I learned something new!

At first I thought these were some strange planktonic creatures, but they were 20-30cm long. They were actively swimming predators that looked like some kind of remote drone submersible. They thrived from the Ordovician to the upper Cretaceous, making it kind of ridiculous that I knew nothing about them until now.