I’m not a taxonomist; early in my career I settled on the model systems approach, which meant all the nuances of systematics disappeared for me. “That’s a zebrafish” and “that’s not a zebrafish” were all the distinctions I had to make, and zebrafish were non-native and highly inbred so I didn’t have to think much about subtle variations. There was one taxonomic boundary one of my instructors forced me to recognize: Graham Hoyle had nothing but contempt for “squishies”, as he called vertebrates like fish or mice or people, and was much more focused on the “crunchies”, insects and crustaceans and molluscs. These seemed like odd ad hoc taxonomic categories to me, I and could think of lots of exceptions where “crunchies” were pretty squishy (see witchetty grubs or slugs), and “squishies” were armored and crunchy (armadillos, any one?), and besides, as a developmental biologist, they were all squishy if you caught them young enough. But OK, if you like dividing everything into two and only two categories, go ahead.

Then today I read this paper, “Dietary diversity and evolution of the earliest flying vertebrates revealed by dental microwear texture analysis”, and saw that there was at least one practical use for the distinction. What you eat affects wear patterns on your teeth, that if you eat lots of crunchy things vs. lots of squishy gooey things, you’ll have a different pattern of dental scratches, and since teeth fossilize — unlike guts — you can get an idea of what long dead animals had for dinner. Furthermore, you can compare fossil microwear textures to the textures in extant animals, where you do know what kinds of things they eat.

This is cool — so you can estimate the range of things ancient pterosaurs ate from how their teeth were worn, whether they ate lots of soft-bodied bugs like flies, or hard-shelled crustaceans, or soft-fleshed fish, by making a fine-grained inspection of their fossilized teeth and comparing them to modern reptiles.

a–c Reptile dietary guilds; a piscivore (Gavialis gangeticus; gharial), b ‘harder’ invertebrate consumer (Crocodylus acutus; American crocodile) and c omnivore (Varanus olivaceus; Grey’s monitor lizard). d–f Pterosaurs; d Istiodactylus, e Coloborhynchus (PCA number 5) and f Austriadactylus (PCA number 2). Measured areas 146 × 110 µm in size. Topographic scale in micrometres. Skull diagrams of extant reptiles and pterosaurs not to scale.

But they’re not done! Knowing the phylogenetic relationships of those pterosaurs, you can then infer evolutionary trajectories, getting an idea of how dietary preferences in species of pterosaurs shifted over time.

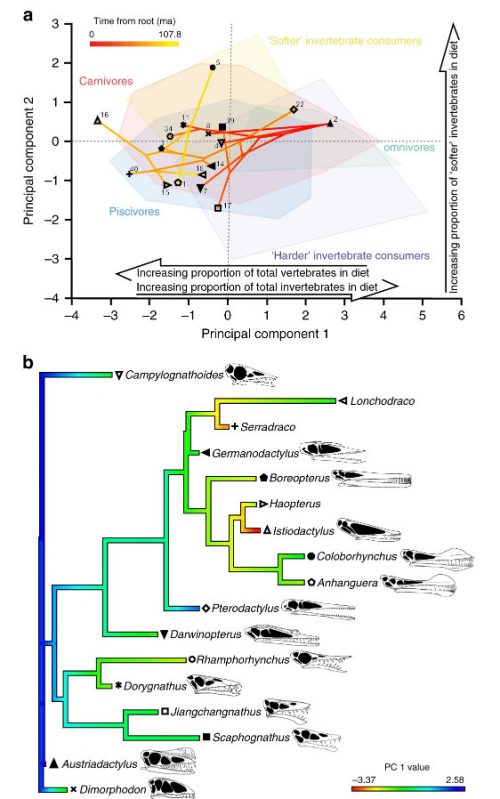

a Phylo-texture-dietary space of pterosaur microwear from projecting a time-calibrated, pruned tree from Lü et al.33 onto the first two PC axes of the extant reptile texture-dietary space. b Ancestral character-state reconstruction of pterosaur dietary evolution from mapping pterosaur PC 1 values onto a time-calibrated, pruned tree from Lü et al.33. To account for ontogenetic changes in diet, only the largest specimen of respective pterosaur taxa, identified by lower jaw length, were included. Pterosaur symbols same as Fig. 2. Skull diagrams of well-preserved pterosaurs not to scale (see ‘Methods’ for sources).

These results provide quantitative evidence that pterosaurs initially evolved as invertebrate consumers before expanding into piscivorous and carnivorous niches. The causes of this shift towards vertebrate-dominated diets require further investigation, but might reflect ecological interactions with other taxa that radiated through the Mesozoic. Specifically, competition with birds, which first appeared in the Upper Jurassic and diversified in the Lower Cretaceous, has been invoked to explain the decline of small-bodied pterosaurs, but this hypothesis is controversial. DMTA provides an opportunity for testing hypotheses of competitive interaction upon which resolution of this ongoing debate will depend.

In summary, our analyses provide quantitative evidence of pterosaur diets, revealing that dietary preferences ranged across consumption of invertebrates, carnivory and piscivory. This has allowed us to explicitly constrain diets for some pterosaurs, enabling more precise characterisations of pterosaurs’ roles within Mesozoic food webs and providing insight into pterosaur niche partitioning and life-histories. Our study sets a benchmark for robust interpretation of extinct reptile diets through DMTA of non-occlusal tooth surfaces and highlights the potential of the approach to enhance our understanding of ancient ecosystems.

So pterosaurs started as small bug-eaters and diversified into niches where they were consuming bigger, more diverse prey over time, which certainly sounds like a reasonable path. I don’t know that you can really assume this was a product of competition with birds — I’d want to see more info about the distribution of pterosaur species’ sizes, because expanding the morphological range doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re losing at one end of that range, but I’ll always welcome more ideas about how Mesozoic animals interacted.

Hey, come on — we “squishies” are crunchy too. We just keep the crunchy parts on the inside.

Seriously, can they really tell the difference between the wear marks due to exoskeletons rather than bones?

As to the shift in predation patterns, could there simply have been more opportunities for crunchy food as time went on, allowing more niches?

Whaddaya know. Acquired taste as a force for evilution.

AFAIK small pterosaurs began gradually disappearing sometime during Cretaceous. This may or may not be related to competition with birds, but I’d think it’s separate from the earlier pterosaur adaptive radiation that had allowed larger pterosaurs to exist in the first place?

@1 From what I recall there was more oxygen in the atmosphere back then and the arthropods were less restricted by their ability to breath so they were able to grow much larger. So yeah It’s not unreasonable to make that leap with wear marks on teeth. When the insects are as big as a cat or dog, why not evolve to eat them?

@4 Ray Ceeya

The high oxygen levels and giant insects were during the Carboniferous period, long before pterosaurs and dinosaurs. I think oxygen levels were actually lower during the Mesozoic than today, they certainly were during the Triassic.

@4

I’ll take your word for it. My knowledge of that sort of deep history is nebulous at best. Still better than Ray Comfort and Ken Ham though.

@6

Low bar there :-)

Comfort and Ham have negative knowledge on the subject.

I’m with DonDueed here. Interesting paper and their methodology was painstaking, but I think they’ve pulled far too much information from the noise of fossilised tooth surfaces.

Ripple effects?

How squids went from crunchy to squishy.

Makes me crabby.

…crabs or calamari, decisions decisions…