Do you want to experience your blood boiling?

I have had a long-time loathing for Winston Churchill, ever since I read about his being the motivator behind the fruitless slaughter of the Gallipoli campaign – a slaughter which was continued far longer than it should have been, because Churchill didn’t want it to be a stain on his political legacy. Basically, he knew he was a great man and by god he was willing to fight to the last drop of some stupid Australian’s blood to prove it. But, I stumbled on this the other day, and it immediately caught my eye because she appeared to be reading a quote by Churchill:

The quote is:

I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.

That’s probably enough from Churchill. But, such a disgusting and inflammatory statement has to have had a context, and perhaps the context was different than it appears to be. No, it was just Churchill briefly saying – in his inimitable way – what the British Empire (embodied as himself) thought of the Arab revolt in Palestine.

But, there is more, of course. There was the Peel Commission (AKA: the Palestine Royal Commission) of 1937, which basically was tasked with figuring out “what the fuck is wrong with those people?” why the arabs revolted. Note the date: 1937 – well before the situation deteriorated past the point of no return and, I argue, plenty of time for the British Empire to do its imperial best to resurrect the situation. Of course, the British Empire wasn’t in the situation resurrecting business; literally every time it encountered a bad situation it tried to ruthlessly suppress it, or (failing that) it left. There probably was, unsaid, a bit of the old “they’re lucky they’re not getting what we did for the Indians after the Sepoy Mutiny” when redcoats strapped trouble-makers alive across the muzzles of artillery pieces which were then fired with a blank charge. It seems to me that the British reaction to the Arab Revolt was relatively mild. But, the important part to me is that their reaction was predicated on not looking too bad and holding the situation together long enough for the locals to sort it out so long as the ageing lion didn’t need to unsheath its claws.

Notes on the Peel Commission from [wik]

The Peel Commission, formally known as the Palestine Royal Commission, was a British Royal Commission of Inquiry, headed by Lord Peel, appointed in 1936 to investigate the causes of unrest in Mandatory Palestine, which was administered by Great Britain, following a six-month-long Arab general strike.

On 7 July 1937, the commission published a report that, for the first time, stated that the League of Nations Mandate had become unworkable and recommended partition. The British cabinet endorsed the Partition plan in principle, but requested more information. Following the publication, in 1938 the Woodhead Commission was appointed to examine it in detail and recommend an actual partition plan.

“unworkable” is such a genteel way of saying “the situation is fucked up.” Remember: the British asked for this – the British took Palestine as essentially their legal spoils after the war, and, honestly, history does not appear to record what they expected to do with it. Presumably, just add it to the empire as another check-box: “Jerusalem? Oh, yes: ours.” The baffling illogic of imperialism; we just want to be able to fly our flag over cool places and gloat. [Yes, cue the Eddie Izzard “do you have a flag?” skit]

The Arabs opposed the partition plan and condemned it unanimously. The Arab Higher Committee opposed the idea of a Jewish state and called for an independent state of Palestine, “with protection of all legitimate Jewish and other minority rights and safeguarding of reasonable British interests”. They also demanded cessation of all Jewish immigration and land purchase. They argued that the creation of a Jewish state and lack of independent Palestine was a betrayal of the word given by Britain.

They were correct in that it was a betrayal of the word given by Britain. But you can’t expect the British to remember such things, they’re too honorable or something.

They were correct in that it was a betrayal of the word given by Britain. But you can’t expect the British to remember such things, they’re too honorable or something.

The Zionist leadership was bitterly divided over the plan. In a resolution adopted at the 1937 Zionist Congress, the delegates rejected the specific partition plan. Yet the principle of partition is generally thought to have been “accepted” or “not rejected outright” by any major faction: the delegates empowered the leadership to pursue future negotiations. The Jewish Agency Council later attached a request that a conference be convened to explore a peaceful settlement in terms of an undivided Palestine. According to Benny Morris, Ben-Gurion and Weizmann saw it “as a stepping stone to some further expansion and the eventual takeover of the whole of Palestine”

The reason I dug into all of this is because I was curious about the question “why is it that people are comfortable saying things like ‘Palestine was never a state’ or ‘The Palestinians were never a people.'” It seems to me that it was and they were, it’s simply that the British never gave them the nod. That’s all. Note that they never gave Israel the nod, either: they left in disgust and the Israelis declared themselves to be a nation, and thus resumed the long process of making sure that Palestine never existed as such.

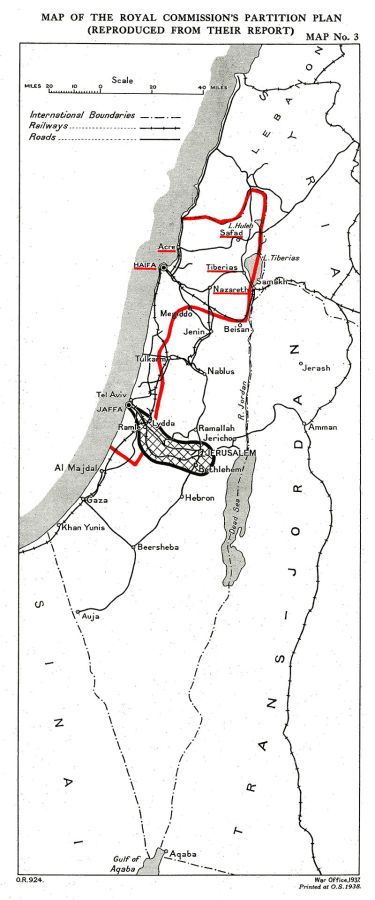

The Peel Commission partition map (left) actually looks moderately sensible, to me. It created an international zone from Jaffa to Jerusalem and Bethlehem, neatly gerrymandering all of the bits of geography that are particularly sacred to one party or the other. The international zone was imagined as some kind of religious disneyland where everyone could put on their bronze-age costumes and go dance around, or whatever. The Jewish homeland would be the area delimited in red, and the rest would become Arab Palestine.

On 20 August 1937, the Twentieth Zionist Congress expressed that, at the time of the Balfour Declaration, it was understood that the Jewish National Home was to be established in the whole of historic Palestine, including Trans-Jordan, and that inherent in the Declaration was the possibility of the evolution of Palestine into a Jewish State.

While some factions at the Congress supported the Peel Report, arguing that later the borders could be adjusted, others opposed the proposal because the Jewish State would be too small. The Congress decided to reject the specific borders recommended by the Peel Commission, but empowered its executive to negotiate a more favorable plan for a Jewish State in Palestine. In the wake of the Peel Commission the Jewish Agency set up committees to begin planning for the state. At the time, it had already created a complete administrative apparatus amounting to “a Government existing side by side with the Mandatory Government.”

That maps pretty accurately to the history as I understand it to have happened (based mostly on O Jerusalem!) and the zionist reaction is as described. Every history I have read on the partition and the creation of Israel is pretty clear that the zionist plan was always to take over the whole area. And there never was a plan for the Palestinians.

As Churchill said:

I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.

That’s the iron fist, with the glove removed. As we’d say nowadays, Churchill said the quiet part out loud.

I am warming myself briefly by the thought of what Churchill, a racist and classist, would have thought of Donald Trump. Trump, of course, would have loved him, while Churchill would have been thinking that the fellow was unsuitable as a dog-walker.

I mean, in the practical sense, Churchill is right (albeit for extremely wrong, immoral and despicable reasons*). There are no natural laws that must be followed by all human beings, and so nobody has an a priori right to exist on a certain bit of soil. We’ve always been a violent and ruthless people, and so only through strength could one group declare their right to a certain place, and dare another to cross them. But when that strength fails, there is always a bigger fish looking for a meal.

Granted, we pretend pretty hard that things are not this way, that as borders became codified, and nation-states of people sharing common culture were created and maintained, the status quo is now the way things “should” be (as the status quo benefits the people who own most of that land). But personally, given the global scale of the challenges we face, and the prospect of the mass migration of perhaps billions of people in the next few decades (as large sections of densely-inhabited land on Earth becomes too inhospitable to support much human life), I don’t think that we can continue to maintain this illusion while ensuring the survival of human civilization. Land (especially temperate, arable land) is too precious a commodity to be owned by those who will only fight for their personal, narrow and short-term interests, rather than working to ensure a future for our species…but I don’t see how we can end our current, increasingly authoritarian model without more authoritarianism, forcing people to share at the point of a gun.

That is the eternal struggle of the leftist – how do we end late-stage, laissez-faire capitalism and bring social justice to those at the margins of the system, just trying to survive, when our tribal identities and natural desire to look out for #1 (evolved characteristics) preclude such behaviour? And how do we bring climate justice to the world when the biggest emitters can’t even legislate reasonable limitations on personal emissions or energy/resource use in general (thus restricting peoples’ freedom to be as environmentally-irresponsible as they want, provided they have the wealth to support those choices)? Any government who tried to do so, to perhaps limit personal, gas-powered vehicle ownership or stop extracting oil or minerals from the ground (when such extraction has traditionally made the regions in which it takes place incredibly wealthy) would be quickly deposed by new politicians vowing to go back to the way things used to be. And by the time enough of the people with the most wealth and power (those who are standing in the way of progress on these issues) realize that they are effectively wrecking their own futures (which they care about far more than those of the billions of other people who share the same planet), and become receptive to changing their behaviour (based on rank self-interest), we’ll all be screwed anyway.

*Were he alive today, would Churchill call himself a “race realist?” I wonder….

VolcanoMan@1>

I take issue with selfishness as an evolved human characteristic.

Our various ancestors spread through six of the seven continents, and extincted most of the mega-fauna already there, before they even figured out metal or wheels. They didn’t do that through sheer rugged individualism or me-me-me attitudes, they accomplished it by working together and taking care of each other (planning and tool making/use also played a large part).

I’m not saying there isn’t an evolutionary pressure to explain selfishness, I just think it’s more of a learned/incentivized thing by our modern society/culture, and I have doubts that it was always as bad as it is now. I’m reminded of that apocryphal quote, I believe frequently attributed to Margaret Mead, about the earliest sign of civilization/society was a broken and healed femur – because it is so debilitating, and takes so long to heal, merely surviving it pretty much meant the individual was being helped by other humans.

I’m not trying to argue with you, I just feel that society tends to ignore/downplay human capacity for teamwork and cooperation. I’m also kinda running a tangent and at risk of derailing…

You know, I think both tendencies are there. But tribalism, and a desire to protect what one perceives as one’s own interests, is certainly an evolved trait. Furthermore, there was always a tribal tendency to attack opponents, not out of a desire to achieve any particular, worldly goal (like gaining land or resources) but just to keep them on their toes, to show that you didn’t recognize their authority over the area in which they operated, and thus to make sure that there was always low-level conflict between their people, and your people (as Daniel Quinn puts it in My Ishmael: “give as good as you get, but don’t be too predictable”). But the concept of land ownership is extremely new, and tribalism, which IS an evolved characteristic, ensures that “peace” between peoples with different ideologies and cultures (etc.) is not something that humanity was ever “supposed” to achieve (according to the dictates of determinism, expressed through the evolution of our species).

So co-operation, while definitely a defining human characteristic, has its limits. I would like to think that we can broadly express this trait and look beyond our superficial differences to bring social justice to places with people whose cultures are alien to us, based on a conception of shared humanity. But that may be naïve, wishful thinking.

@1 and 2:

I believe that our society tends to focus excessively on competition (e.g., sports, or the “competition” of evolution), conveniently forgetting the cooperative, community-based elements (successful team employ cooperation, a herd is just another name for a community of cooperating animals).

So, I say, we have enough talk of competition, and need instead to start stressing the other “c-words”, like community, cooperation, caring, etc.

Not to defend churchill, but gallipoli was a sound strategy. We had all these pre-dreadnought battleships which were useless in the atlantic and north sea against the german fleet.

Why not send them against the ottomans where they can fight? Obviously it didn’t turn out so well.

@4 jimf

The key to co-operation is that it happens within communities, with shared identities and goals. I do think that the conception of a community (or in-group) has expanded since the early days of humanity (when a community might include only a few dozen people), but to improve our prospects at survival into the future, it must expand MUCH more. Unfortunately, there are those (throughout the world, certainly, but also within nations like America) with a vested interest in fragmenting humanity, playing their group against all others by using fear and primal xenophobia. They do this because it is a reliable way to achieve power; even at the height of Obama’s popularity, where the senator and then president successfully brought tens of millions of people together with a message of hope instead of fear, the Tea Party started to grow from the roots of the racial resentment of the civil rights movement, and the seed of the very birth of America as a land where all men were not created equal, or treated as such. And on a more global scale we constantly see the us vs. them thinking of extremist groups, deliberately trying to re-make the world in their image by stifling all other ideologies and even the ability to express dissent as an interpretation of the “approved” cultural standards (the Catholic Church spent centuries of Inquisition doing just this, but everyone from the Soviet bloc to ISIS have attempted something similar).

So I agree – as humans, we certainly have the evolved ability to work with others, achieving greatness to which we could never even aspire, working in smaller groups or alone. But never forget that much of that co-operation was implemented in the successful persecution, and often eradication of out-groups with different beliefs and values. The British Empire was an incredibly efficient machine of conquest and colonialism, and so many others achieved similar success (the Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese and even French managed to maintain empires for a time, weaponizing their in-group solidarity, and much-vaunted “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” ethos to destroy entire cultures). Expanding our in-groups means recognizing the monumental feat it is, to go against what seems to be an almost inevitable characteristic of human societies (indeed, most of the pre-colonial cultures that the Western nations erased in their colonial ambitions were themselves perpetually involved in their own competitive affairs, brutally suppressing those who THEY viewed as out-groups). I think it would take an entirely different way of conceptualizing what it means to be human to overcome our nature.

I don’t argue that “cooperation” has often been corrupted to serve an in-group/out-group dynamic. That’s not my point. What I am saying is that each of us must challenge the narrative. When people start talking about competition being the primary natural force between individuals (or even between groups), we must challenge it with the other C words, like community, cooperation, compassion, caring, and the like. You’d never get that idea from a typical nature documentary, but that’s only because they continue to reinforce the existing bias.

As an aside, let me add that I see this from the perspective of someone who was successful in highly competitive sport (distance running). “Competition” was THE word. Fortunately, it was not too long before I realized that my best performances came via cooperation and community. Ultimately, the only truly meaningful competition was you and the demons in your own head. The happy realization is that other people could help you overcome them. Unless you’re at the pinnacle of sport (where your livelihood comes from), the goal is not to beat other people, it’s to beat the demons that say that you cannot perform at a higher level. That is, to push yourself beyond.

Try the new Might Makes Right™, now with added racism!

Question: is there a hard upper limit on how many people you can be persuaded to consider your “in-group”?

I’d have assumed, naively, that since we evolved to move and live in groups of about 50ish (?), that you’d have a hard time getting people to consider much more than that as their in-group. I’m obviously wrong, because you can readily get more people than that to chant “USA! USA!” or whatever other bullshit you like, or indeed volunteer to join and army to go and teach a lesson to the dashed Hun. Ultimately, though, doesn’t there HAVE to be an outgroup?

It’s a trope in sf that we only manage to pull together when a non-human outgroup manifests itself, i.e. aliens turn up and we forget our differences to beat them. Well, aliens aren’t going to turn up… but could AI be the outgroup we need to grow up work together?

Just random thoughts…

I’ll follow up with some random thoughts of my own:

I think it relates to how all groups are essentially artificial and based on ignoring the bits where we are different. Or said more kindly: Deciding that there’s something else that’s more important than our differences.

People can be motivated to be group-minded through personal relationships (sure, Joe is different from me, but we’re old pals) or because there’s something else that draws more attention (sure, Joe is different from me, but I need his help to defeat the whatevers-over-the-hill).

The outside force works so well because, while mistreatment will undermine personal relationships, it won’t necessarily undermine the need for the protection of the group. Even if the group is treating you poorly, “those guys” are worse, so you stick with the group anyway. This allows the group to survive problems that would destroy it, if it were based only on personal relationships.

And this also explains why groups become dependent on the outside threat. The moment it’s gone, all those problems that have been swept under the rug come back in force.

@sonofrojblake:

I have often noticed that 35-50 seems to be an upper functional limit on human groups. Mostly I noticed this in military organization since basically forever. It may be an evolved in tendency or a factor of how we speak and use language.

Something else Churchill found acceptable to use in the”uncivilised” Arab world:

Excerpt from pages 179-181 of Simons, Geoff. Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam. London: St. Martins Press, 1994:

“Winston Churchill, as colonial secretary, was sensitive to thecost of policing the Empire; and was in consequence keen to exploit the potential of modern technology. This strategy had particular relevance to operations in Iraq. On 19 February, 1920, before the start of the Arab uprising, Churchill (then Secretary for War and Air) wrote to Sir Hugh Trenchard, the pioneer of air warfare. Would it be possible for Trenchard to take control of Iraq? This would entail “the provision of some kind of asphyxiating bombs calculated to cause disablement of some kind but not death…for use in preliminary operations against turbulent tribes.”

Churchill was in no doubt that gas could be profitably employed against the Kurds and Iraqis (as well as against other peoples in the Empire): “I do not understand this sqeamishness about the use of gas. I am strongly in favour of using poison gas against uncivilised tribes.” Henry Wilson shared Churchills enthusiasm for gas as an instrument of colonial control but the British cabinet was reluctant to sanction the use of a weapon that had caused such misery and revulsion in the First World War. Churchill himself waskeen to argue that gas, fired from ground-based guns or dropped from aircraft, would cause “only discomfort or illness, but not death” to dissident tribespeople; but his optimistic view of the effects of gas were mistaken. It was likely that the suggested gas would permanently damage eyesight and “kill children and sickly persons, more especially as the people against whom we intend to use it have no medical knowledge with which to supply antidotes.”

Churchill remained unimpressed by such considerations, arguing that the use of gas, a “scientific expedient,” should not be prevented “by the prejudices of those who do not think clearly”. In the event, gas was used against the Iraqi rebels with excellent moral effect” though gas shells were not dropped from aircraft because of practical difficulties

morsgotha@#5:

Not to defend churchill, but gallipoli was a sound strategy. We had all these pre-dreadnought battleships which were useless in the atlantic and north sea against the german fleet.

Why not send them against the ottomans where they can fight? Obviously it didn’t turn out so well.

Yes, and no. When I was younger I’d have said that the problem was that they brought along the French Navy, which was their main mistake. But it’s more complicated than that. Obviously, the attempt to force the Dardanelles might have been an OK idea, if it had worked, but it never came close to working. And then Churchill doubled down, again and again, in blood and death. If he had simply called things off when the attempt to run the straits had failed, then he’d have been a visionary. But he was blinded by his own racism and did not take “Johnny Turk” seriously enough basically launching an assault by a stretched logistical line against a local logistical line anchored at a major city, manned by the forces of a significant imperial power.

Churchill was fighting to protect his career, and there was no drop of other people’s blood he was unwilling to shed in that cause.

benedic@#12:

Churchill was in no doubt that gas could be profitably employed against the Kurds and Iraqis

I am vaguely reminded of Christopher Hitchens’ phony outrage about the gassing victims at Halabja. Or maybe he believed it. It’s hard to know and now we’ll never.