Our story begins with a decision by The King’s Bench, Somerset V Stewart.

The Gavel Heard ‘Round The World

Writing from the bench, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield knew his decision was going to be far-reaching, but he considered it unavoidable:

Mansfield

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasions, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory. It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from the decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.

The Somerset case revolved around a situation that had already occurred several times before: a slave owned by an American colonial had been brought with his owner to England, whereupon the slave ran away, taking advantage of England’s much more lax enforcement environment. In the colonies, at the time, a slave-owner whose slave ran away could fall back on the fact that slavery was a huge and vital piece of the economy, and there were professional slave-catchers and a whole legal infrastructure supporting slave-owner’s rights. In England, that infrastructure was largely absent, and abolition – while not the law of the land – was certainly a respected position.

Mansfield made many attempts to resolve the case without a decision – in the past, similar cases had been swept under the carpet by the simple expedient of having the court consult with a slave-owner and relinquish their claim. That allowed the case to not happen, thus not requiring a decision to happen either. In Somerset, the law was not let off the hook, and Mansfield wrote his decision – his words do not need adornment but bear close examination:

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasions, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory.

He is saying, in other words, “it’s currently legal in some places but it’s wrong that it’s legal.” Plato’s Socrates could not have done better – if the law is about justice, we cannot uphold this person’s claim that they own this other man; it’s inherently immoral to do so, and a court concerned with justice cannot decide otherwise.

The date was May 14, 1772.

The Odious Institution

The colonies in America had been priming themselves for a revolution for some time. Unpopular legislation from England, in the form of taxes and regulations – notably The Stamp Act, The Sugar Act, The Townshend Act – had provoked protest, violence, tax collectors being brutalized, and civilian protestors shot down by redcoats. England was trying, simply enough, to extract some of the colony’s massive wealth through taxation, to pay for its various wars. The colonial leaders were trying, simply enough, to keep their wealth – a great deal of which was at best semi-licit: whenever the crown would levy a new tax, the colonial entrepreneurs would smuggle the goods, anyway.

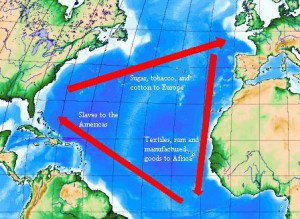

The “triangle trade” was taking place “off the books” to a significant degree,

(wikipedia)

and was at least partly designed to facilitate smuggling. It was a hugely profitable trade-route, and underpinned much of the New England economy as well as that of the American south’s most powerful and wealthy state, Virginia. From 1770 to 1780 the people who became the political leaders in the colonies were all wealthy, and that wealth depended on smuggling, slavery, land speculation, tobacco or cotton farming, or “trade” (which meant: buying and selling alcohol, tobacco, slaves, etc) – the unhappiness the colonial political leaders were feeling with England was that their tax-sheltered existences were threatened. They were already hugely wealthy, in terms of the time, with some notable exceptions (Jefferson was really really good at spending money!) George Washington was the largest land speculator in the colonies, John Hancock was a smuggler “trader” of large but unknown fortune, Jefferson owned lots of land, slaves, and farmed tobacco and cotton.* They had time and inclination to get involved in politics because they had a great deal of wealth at stake and had enough wealth that they could take the time – literally afford – to travel about protecting their interests.

For the colonial elite, the Somerset decision had the attention-riveting effect of a dagger pressed against the throat. It was immediately seen as a threat to their interests for the simple reason that: the colonies were under England’s law. If English law had finally come down on the issue of slavery as odious, immoral and – what really mattered: unenforceable – the colonial elite had a serious, serious problem on their hands.

So they did what any justice-loving group of leaders would do: they worked out how to emancipate the slaves, apologized and compensated them with grants of land** and started tithing a reasonable percentage of their gains to England.

Of course they didn’t.

Committee of Correspondance … About What?

The colonial politicians – most of the “Founding Fathers” – had established committees of correspondance – proto-government factions that coordinated the activities of nationalist Americans. They weren’t simply propaganda arms, though they sort of fulfilled that purpose, as well: one of the matters the committees corresponded about was interpretations of English law, how taxes affected the colonists* and establishment of the colonial “party line” on political affairs. There was considerable communication about the implications of the Somerset decision. Especially from the nationalists in Virginia – a state that’s entire economy, as far as its wealthy were concerned, was tied up with slavery in one way or another. There, the familiar cast of characters – Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee**** – turned up, establishing the colonials response to the actions of England.

Letters in archives from the committee members show that they were concerned about the Somerset decision. After all, how could they not be? Slavery was one of the yardsticks of their wealth, as long as an enabler of their wealth, and taxation and abolition were two barrels of a shotgun staring them in the face.

Calling it a “propaganda campaign” may be going too far, but, well, the colonial leadership began to frame the resistance to England in terms of two matters:

- They are taking our rights away

- They are taxing us

Thomas Hutchinson, Governor of Massachusetts

Which “rights” were the English taking away from the colonials? As subjects of the crown, under crown law, there wasn’t any actual attempt by England to take any of the colonials rights away, at all. Unless, of course, you mean their “right” to own people.***** A third item came from that: “No taxation without representation” – i.e.: England had no right to tax the colonists if the colonists didn’t have seats in Parliament. On the face of it, that’s a specious argument – the colonists were citizens of England and were subject to English law, with one odious exception, and were represented in Parliment through a system of crown-appointed governors and the rest of the parlimentary panoply. What the colonials meant was “we don’t like the representation we are getting” and “ow! taxes!”

What about the rights that England was taking away from the colonists? The patriots scored a propaganda coup by publishing some letters from Governor Hutchinson of Massachusetts, in which he observed that it was impossible for the colonials to have the full rights of English subjects and that it was necessary to curtail their liberties. The colonial politicians began spreading the idea that the English were taking away the rights of the colonists, and were taxing them unfairly, and that “no taxation, without representation” – that the colonists had a right to be politically involved in setting the taxes and laws they lived under. You can see, already, the problem: they wanted to be able to vote against the taxes they didn’t like but they were guaranteed to always lose such a vote, and they wanted to preserve the “state’s rights” for each colony to have its own laws superceeding the crown’s. Nobody came right out and said it had anything to do with the Somerset decision, because nobody had to: Somerset meant slaves could no longer be held legally in England. The colonial leaders wanted to nullify Somerset.

At this point, you are probably thinking something like “Wow! This sounds … familiar!” From a standpoint of law, the colonists were arguing that they were being oppressed by having their right to oppress taken from them. From a standpoint of secession, the colonists were not actually interested in negotiating representation at all because if they achieved representation, they would be outnumbered anyway. The secession argument was a fig-leaf for protecting slavery. The taxation argument was a fig-leaf for protecting massive smuggling in sugar, tobacco, human beings, and alcohol.

1860 was a replay of 1776 with the subtle difference that the northern states had managed to build industrial economies that no longer depended on slavery, so the northern oligarchs no longer had to protect that right.

Wheeling and Dealing

After the revolution began, and succeeded, the winners sat down to divide the spoils. No longer under English law, Somerset didn’t count anymore and the founding fathers of the new United States of America were able to wrangle over how and where to include slavery in the economy of the country. There is a great deal of additional history worth studying, over whether or not Jefferson tried to spin slavery in the declaration of independence, or who traded what quid for whatever quo: but the damage had been done – a new country was created, separated from England, by a cabal of wealthy smugglers, tax dodgers, and trafficers in human bondage. The history we are taught in the United States of America continues to uphold the “no taxation without representation” message but ignores the question of what was being taxed and why those taxes were or were not unfair.

Thomas Jefferson owned hundreds of slaves and they toiled at his 5,000 acre plantation. He raped one of them, the 14-year-old Sally Hemings, who bore him several children. Two of his children he allowed to “escape” to freedom, and the other two were freed through his will at his death. Those were the only slaves that were ever freed from Jefferson’s chains. Hemings was put out to pasture and lived as if she were free and the remainder of Jefferson’s slaves were sold to pay off his debts.

George Washington owned hundreds of slaves (300+ at his death) and left instructions to free his slaves after his wife, Martha, died. So, making sure to lead the comfortable life of an oligarch, he allowed the great leveller, death, to do what he claimed to want to do all along.

Benjamin Franklin owned slaves and only publicly changed his views shortly before his death. His newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, carried advertisements for slave traders and slaves for sale. In 1790 he petitioned congress to end slavery – 28 years after the Somerset case had ended slavery in England, and three years before his death.

Patrick “Give me liberty or give me death” Henry’s sentiments probably were echoed by the 60 slaves he owned, who worked his 10,000 acre plantation.

John Hancock only owned one personal slave for household work, but as a “merchant” and smuggler, built his fortune out of sale of slaves, and products made and harvested by slaves.

Whitewashed history proclaims that Samuel Adams never owned slaves, but there was a slave – Surry – given to his wife, who Adams supposedly planned to emancipate but all the paperwork got bogged down and it took years and years and never happened. Surry’s services must have been indespensable.

Richard Henry Lee owned Stratford Hall, 16,000 acres of Virginia farmland, and many slaves. His descendant, born in Stratford Hall, commanded the Confederate army in the second american rebellion over slavery.

It appears that the only “founding father” who didn’t own slaves was Thomas Paine. Paine left a modest estate to his girlfriend, French revolutionary Nicholas Bonneville’s wife, Marguerite Brazier.

Afterthoughts

I started studying this topic several months ago, when I wondered one day what exactly was the relationship between English abolition and the US Revolutionary war. I was actually expecting to learn that abolition had been imported into the US by Quakers coming from England, or something. It turned out that that was also sort of true – but it’s impossible to dig a little ways into this topic without stumbling across the Somerset case and then you simply cannot avoid noticing that 1772 happened not long before 1776.

As I started researching that question, I quickly found “Slave Nation” by Alfred and Ruth Blumrosen. It makes what I’d call the “strong claim” for slavery’s impact on the start of the revolution – that it was all because of slavery. I’m unconvinced of the strong claim, but the weak claim: that slavery was a significant factor in the revolution, is, I think, unavoidable. Blumrosen goes into more depth about various letters between Jefferson and Adams referring to the Somerset case, and so forth – frankly, I don’t find that there’s any more need for convincing once you ask yourself the question “what liberties are the English taking away from the colonists that they are so riled up about?” I have tried to reflect that in how I present this material.

My father’s a historian, and happened to call me the other day about something unrelated. We chatted for a few minutes and I asked him what he thought about this topic. “Ah. Yes. That’s something that’s pretty obvious to any historian, but the question is: what do you make of it?” Indeed.

My philosophy of causality is that humans don’t understand cause and effect very well (or at all!) in large systems, and we tend to point to something that’s a plausible cause and say “well, there, that’s it!” In a sense, that’s what the Blumrosens did: they correctly identified slavery as a major factor in the revolution, and – as part of refining and making their case – they filtered out many other factors. In Marcus-land, I’d say that it’s unquestionable that slavery was one of the primary detonators of the revolution, but that the French/Indian war (and attendant taxation) and stupid English colonial policies also played a part. “It’s not so simple” which is why I don’t agree with the Blumrosens strong claim. I urge you to do your own research and draw your own conclusions. In this article, I’ve linked sufficient pieces of information that – if you follow and absorb them and then critically assess them in the light of whatever other research you do – you’ll be qualified to have an opinion on this topic.

I’m as inclined to say that the american revolution was the consequence of a group of opportunistic, wealthy, oligarch tax-cheats and sleazeballs who manipulated public opinion to protect the vast fortunes they managed to extract from other people’s blood, sweat, and tears. The United States of America was built on destroyed lives and the revolution was fought to preserve the oligarchy’s ability to enslave their fellow human beings. I don’t think the revolution happened and the founding fathers became oligarchs. I think the founding fathers became oligarchs by theft, inheritance, and hard work******* – and the revolution happened as the oligarchs protected their position. They certainly were not great men, nor were they great political thinkers. Their greatness was in their ability to dupe a largely ignorant populace that was busy just surviving. The brilliance of their creation was to kick the can down the road on slavery for further generations to deal with – and die over.

The founding fathers did not create a great country, they created a shambles in order to foster what became the seeds of its own destruction a mere 100 years later. The same script has been played over twice so far and if you hear someone talk about secession, in this country, they are following a tradition: The Great American Dupe-hood. Donald Trump and Thomas Jefferson are shit stamped in the same mold, but Jefferson had better hair.

As I write this, Bill O’Reilly, who – in colonial times – would be treated as subhuman (Assuming O’Reilly indicates Irish descent) is bemoaning that Michelle Obama had the temerity to remind us that the White House was built by slaves. That’s absolutely true. The whole fucking country exists because of slaves.

(* More precisely: slaves farmed tobacco for him)

(** Taken from the Indigenous Peoples, naturally!)

(*** And, by “colonists” we mean “colonial oligarchs” Most of the issues around slavery and taxation didn’t affect the lower, agrarian, and working class at all)

(**** Yes, “those” Lees)

(***** I feel like this article should be liberally salted with “scare quotes” except it would be about 80% “scare quotes” around most of the text. Instead of doing that, I have tried to write in such a way as to indicate what I think is bullshit and what isn’t. In case I have failed in that regard, let me be clear: the colonials were slinging a very great deal of bullshit, indeed.)

(****** A lot of that hard work being done involuntarily by slaves)

Fascinating.

Thanks for the read.

It depends on exactly what time. As I’m sure you know, there were several other important rights that were being infringed. For example, import inspectors with their general warrants AFAIK were quite abusive with their general warrant search powers. Also, the later decision to have a standing army to enforce the law, and where the persons in the standing army are immune to civil and criminal sanction by the people through private civil and criminal trial. Being forced to house and quarter a standing army. The final spark for the war was the British attempt to seize the arms of the people of several cities. — I’m not trying to distract from your point and article. It’s really quite fascinating. Thanks again!

I’d still debate that.

I recently read an article in the Smithsonian magazine about Jefferson and slavery. Basically, it turns out that he was way worse than we thought.

One point that was made was that he shouldn’t be left off the hook because “the standards of the day were different than they are today.” There were abolitionists back then, and they read the same Declaration that we read, and looked to Jefferson as a natural leader. And he stiffed them, and equivocated, and rationalized, and basically talked himself into becoming a full-blown racist apologist for slavery.

The problem was that he was not only prodigal with his money, but also a fairly poor farmer. However, he stumbled across an enterprise that allowed him to make money hand over fist — a nail-making business. For many years, this was pretty much the only thing keeping him afloat with his fancy inventions and entertaining with imported wines.

The nail makers weren’t just slaves — they were slave kids: boys from around 10-15. And Jefferson wanted results. If the rate of nail-making slacked off, he wouldn’t necessarily blame the slaves, but he’d blame the overseer — then hire a different overseer who got better results. That usually involved whipping. Jefferson wasn’t necessarily directly involved, but he definitely knew what was going on and looked the other way, all the while rationalizing the heck out of it.

This wasn’t generally taught about Jefferson, because a few decades ago, the record books of his farms were published so that they would be widely accessible. But the professor who edited them decided that all of records of children getting whipped wouldn’t reflect well on the image of his hero he wanted to portray, so he quietly edited those bits out. It’s only recently that other scholars went back to the originals and noticed the deletions.

The saddest part is, Jefferson probably really believed in the words he wrote in the Declaration about slavery when he was young. I think the lure of easy money, along with the absolute power of being a plantation owner, corrupted him. Getting older and richer can be a scary thing sometimes.

Something I thought might be relevant, here:

Why We Should All Regret Jefferson’s Broken Promise to Kościuszko

Jefferson was basically offered a huge amount of money for the purpose of freeing slaves (his own or others, as the text says) — and then later declined to do any such thing, despite having initially agreed to do so.

Owlmirror @3

I heard an interview om CBC Radio’s Saturday Night Blues Partywith the composer of the Freddie King song Going Down. The composer had a friend who was from Kosciusko, Mississippi (which he said was named after a Polish General) so he had a line about going down to Kosciusko in the song. However, Freddie King had so much trouble pronouncing Kosciusko that he sang “Going down to Tuscarora” (there is no such town in Mississippi) instead. I had always wondered why a town in Mississippi was named after a Polish General and had zero chance of spelling the name well enough to find out. Now I know – thanks.

Marcus, you are just one of those leftist liberal commies who wants to tear down our exceptional country. Everyone knows that the founding fathers were perfect in every way and always did the right thing. (/snark)

In all seriousness, a great analysis and summary. Thanks for doing the digging! I appreciate your sharing of your knowledge.

Regarding Jefferson in particular, and staying in the land of entertainment rather than detailed history, I like this from Lin-Manuel:

A civics lesson from a slaver. Hey neighbor

Your debts are paid cuz you don’t pay for labor

“We plant seeds in the South. We create.”

Yeah, keep ranting

We know who’s really doing the planting

Speaking of which,

How are you defining “founding father”? The link there lists several non-slaveowners, including Hamilton.

Still absorbing most of this so don’t have more than an off the cuff comment. But from what I read here it sounds like the tea party republicans of today aren’t as poorly named as I originally thought.

Johnny Vector@#5:

How are you defining “founding father”? The link there lists several non-slaveowners, including Hamilton.

I didn’t try to define that. I’m thinking of “founding fathers” as a nebulous cast of characters around the declaration of independence and shortly after.

With regards to Hamilton, he did own slaves:

https://www.varsitytutors.com/earlyamerica/early-america-review/volume-15/hamilton-and-slavery

I think that description is fair – Hamilton was very much a social climber and wanted to have all the things of a person of his new class. Including slaves.

johnson catman@#4:

Everyone knows that the founding fathers were perfect in every way and always did the right thing

Going into this I had some residual respect for Ben Franklin, because: lightning rods! But it doesn’t survive very long. I think Franklin was probably the least despicable of the bunch, but he was also pretty cheerfully throwing his fellow man under the bus because freeing him would be such a great big inconvenience.

The obligatory veneration of the founding fathers as great political minds now sounds to my ear like the praises heaped on Kim Jong Un: propaganda written by people raised on propaganda.

Owlmirror@#3:

Jefferson was basically offered a huge amount of money for the purpose of freeing slaves (his own or others, as the text says) — and then later declined to do any such thing, despite having initially agreed to do so.

Ouch, what a creep. It’s not really possible for him to sink lower in my estimation, but – favoring his convenience over the freedom of those people: what a horrible hypocrite.

De Lafayette wrote:

I would never have drawn my sword in the case of America, if I could have conceived the thereby I was founding a land of slavery.”

Marcus:

That link doesn’t actually provide any evidence that Hamilton owned slaves, and a lot that he held conflicting views about it. He clearly supported institutions, including his family by marriage, that did own slaves. But as for actually owning any, all that article has is “he was accused of owning slaves, by scholars and his grandson”, which is pretty thin gruel, along with being unsourced.

Anyway, I was just curious about why you chose one of the 7 founding fathers listed in the Britannica article as being the only one who didn’t own slaves. I figured you had a different definition of “founding father”. Not that any of that changes the main point of your post.

EnlightenmentLiberal@#1:

As I’m sure you know, there were several other important rights that were being infringed. For example, import inspectors with their general warrants AFAIK were quite abusive with their general warrant search powers.

Yeah, Hutchinson appears to have adopted the aristocratic stance that the colonists just needed a good thrashing to bring them in line. There were lots of abuses and impositions, no question about that. That’s where I think things get slippery – the strong case, that it was all or mostly slavery that triggered the revolution: I don’t buy it. But the weak case, which the Blumrosens make, is that the reference to “taking our liberties” is vague because the colonists didn’t want to say what liberty was being taken. They had no problem complaining about taxation, or specific taxes, or levying or having soldiers lodged, or impressment, or any of the many other complaints. But there’s this big “liberties” thing that remains unspecified. I think there’s something to that. I will perhaps do another posting lifting the Blumrosens’ arguments instead of making my own – they did a lot of (cherrypicking? or close reading?) review of the various correspondance between Adams and Jefferson and the other members of the committees. Some of the pieces they identify, including some letters with Ben Franklin, do a lot to bolster their case. Though, again, maybe the complaints were suspiciously abstract. Perhaps I am reading them through the 20th

I’m not trying to fight that partiocular point with you, and I really appreciate your comment. I am not sure whether I should belabor it further or not.

Also, the later decision to have a standing army to enforce the law, and where the persons in the standing army are immune to civil and criminal sanction by the people through private civil and criminal trial. Being forced to house and quarter a standing army.

Those aren’t “liberties” and were already specifically complained about in those terms.

Johnny Vector@#10:

That link doesn’t actually provide any evidence that Hamilton owned slaves, and a lot that he held conflicting views about it. He clearly supported institutions, including his family by marriage, that did own slaves.

Yes, that’s true. … And, of course he helped create and support a political regime based on slavery. It’s pretty hard to say his hands are clean.

So I’ll stand corrected about the “only” founding father. But, in my book, Hamilton is still an oligarchic bastard who created a slave state and profited hugely thereby.

brucegee1962@#2:

One point that was made was that he shouldn’t be left off the hook because “the standards of the day were different than they are today.” There were abolitionists back then, and they read the same Declaration that we read, and looked to Jefferson as a natural leader.

I think I’m going to have to lift some bits from the Blumrosens into a future post. Jefferson was quite aware of the fact that slavery had effectively been made illegal in England by 1772. So “the standards of the day were different than they are today” – does that apply to the standards of an educated person of 1772, or the standards of an apologist for slavery of 1776? Blumrosens quote letters from Jefferson that make it sound an awful lot like he was very concerned about how much money certain wealthy virginians might lose if the Somerset decision became the law of the land in the colonies.

[About the nail-makers]

AAARGH!

I read Jonathon Sistine’s biography of Jefferson a few years ago, back when I was listening to the Thomas Jefferson hour podcast. (Which is good fun but gets boring after a few episodes) It mentioned the nail making business but was silent about the actual part about who made the nails. Unless my memory is failing me. Generally my recollection of all the US history I’ve read is that it’s very delicate about who did what actual work. “Oh, you know, Jefferson was a farmer.” One that probably seldom touched soil. The money he was being so profligate with was earned for him by the many slaves he owned.

The saddest part is, Jefferson probably really believed in the words he wrote in the Declaration about slavery when he was young. I think the lure of easy money, along with the absolute power of being a plantation owner, corrupted him. Getting older and richer can be a scary thing sometimes.

I agree – it seems that way to me, too. Power doesn’t corrupt quickly. But it corrupts eventually.

To Marcus Ranum

Again, I was just playing a little contrarian and/or devil’s advocate. I was offering a pedantic “correction”. I tried to say, and I’ll say again, that I do not mean to diminish your point, and your overall point makes a great deal of sense. I fully agree with what you said here:

PS:

I just wanted to emphasize that there were other “complaints” that today we might frame as liberty issues, even though at the time they might have used different language. AFAICT, as written in the American Declaration Of Independence, they would use terms like “Civil Power” to describe the ability for a private person to take civil or criminal action against a murderer. Still, I am probably far less read on this than you. I need to do more reading.

PPS:

Again, thanks again for your wonderful posts. And thanks for taking the time to reply! It means a lot.

militantagnostic@#4:

The creation of the US owes a lot to “foreign fighters” – Lafayette, Kosciusko, Von Steuben, etc.

As my quote from Lafayette @#10 indicates, some of them regretted what they were involved in.

I believe there is truth in the idea that slave-owning oligarchs and smugglers were a significant force behind the impetus for independence. But there were other forces at work as well. Many in the Northern colonies were against slavery, but they didn’ t have the clout to buck the South. The reason the slavery issue was left for later generations is that without the support of the Southern colonies, there would have been no consensus for independence. And without slavery, there would be no Southern support. Yes, it was a very messy compromise, and we are still paying the price. But to say that the country was built solely on slavery ignores the immense contributions of subsequent generations of Americans and immigrants, including freed slaves and their descendants, who sweated, toiled and died trying to build a better life. As for Jefferson, he is portrayed in American folklore as a great hero of the Republic, when in fact he was a snake–a backstabber and a hypocrite. If you read David McCullough’s biography of John Adams you will find numerous examples of his dirty dealings. In contrast, Adams, who was one of the true heroes and driving forces in our move toward independence, owned no slaves, was not wealthy, earned his living by his own labor, and was a man of unswerving principle. even if he was an arrogant pain in the ass. It’s time to dispel the Jeffersonian myth and let the public know what a two-faced son-of-a-bitch he really was. Put Adams on the nickel and the two-dollar bill–at least he deserves to be there.

publicola@#17:

The reason the slavery issue was left for later generations is that without the support of the Southern colonies, there would have been no consensus for independence. And without slavery, there would be no Southern support. Yes, it was a very messy compromise, and we are still paying the price. But to say that the country was built solely on slavery ignores the immense contributions of subsequent generations of Americans and immigrants, including freed slaves and their descendants, who sweated, toiled and died trying to build a better life.

That’s true, but when you say that there would not have been a country without those compromises, you’re agreeing with me: the country would not have happened otherwise, i.e.: it was built on slavery. The people of good will who toiled to build the country did so in a framework that politically negated any attempts they may have had to achieve their own freedom or that of their fellow man.

Scene on Radio podcast just started their Season 4, which includes a bunch more about what venal bastards the founding fathers were. [here]

My feeling is that most of us who are trying to get Americans to re-see the founding are being understated, rather than overstating the case. These are people who wanted their own country so they could protect the money they had ‘earned’ and were willing to doom huge numbers of their fellow men to poverty and slavery in order to protect their wealth.

@18: Fair enough.