Work means everything to us Americans. For centuries – since, say, 1650 – we’ve believed that it builds character (punctuality, initiative, honesty, self-discipline, and so forth). We’ve also believed that the market in labour, where we go to find work, has been relatively efficient in allocating opportunities and incomes. And we’ve believed that, even if it sucks, a job gives meaning, purpose and structure to our everyday lives – at any rate, we’re pretty sure that it gets us out of bed, pays the bills, makes us feel responsible, and keeps us away from daytime TV.

These beliefs are no longer plausible. In fact, they’ve become ridiculous, because there’s not enough work to go around, and what there is of it won’t pay the bills – unless of course you’ve landed a job as a drug dealer or a Wall Street banker, becoming a gangster either way.

These days, everybody from Left to Right – from the economist Dean Baker to the social scientist Arthur C Brooks, from Bernie Sanders to Donald Trump – addresses this breakdown of the labour market by advocating ‘full employment’, as if having a job is self-evidently a good thing, no matter how dangerous, demanding or demeaning it is. But ‘full employment’ is not the way to restore our faith in hard work, or in playing by the rules, or in whatever else sounds good. The official unemployment rate in the United States is already below 6 per cent, which is pretty close to what economists used to call ‘full employment’, but income inequality hasn’t changed a bit. Shitty jobs for everyone won’t solve any social problems we now face.

Don’t take my word for it, look at the numbers. Already a fourth of the adults actually employed in the US are paid wages lower than would lift them above the official poverty line – and so a fifth of American children live in poverty (edit Charly 17.06.2023 – new link). Almost half of employed adults in this country are eligible for food stamps (most of those who are eligible don’t apply). The market in labour has broken down, along with most others.

[…]

But, wait, isn’t our present dilemma just a passing phase of the business cycle? What about the job market of the future? Haven’t the doomsayers, those damn Malthusians, always been proved wrong by rising productivity, new fields of enterprise, new economic opportunities? Well, yeah – until now, these times. The measurable trends of the past half-century, and the plausible projections for the next half-century, are just too empirically grounded to dismiss as dismal science or ideological hokum. They look like the data on climate change – you can deny them if you like, but you’ll sound like a moron when you do.

For example, the Oxford economists who study employment trends tell us that almost half of existing jobs, including those involving ‘non-routine cognitive tasks’ – you know, like thinking – are at risk of death by computerisation within 20 years. They’re elaborating on conclusions reached by two MIT economists in the bookRace Against the Machine (2011). Meanwhile, the Silicon Valley types who give TED talks have started speaking of ‘surplus humans’ as a result of the same process – cybernated production. Rise of the Robots, a new book that cites these very sources, is social science, not science fiction.

So this Great Recession of ours – don’t kid yourself, it ain’t over – is a moral crisis as well as an economic catastrophe. You might even say it’s a spiritual impasse, because it makes us ask what social scaffolding other than work will permit the construction of character – or whether character itself is something we must aspire to. But that is why it’s also an intellectual opportunity: it forces us to imagine a world in which the job no longer builds our character, determines our incomes or dominates our daily lives.

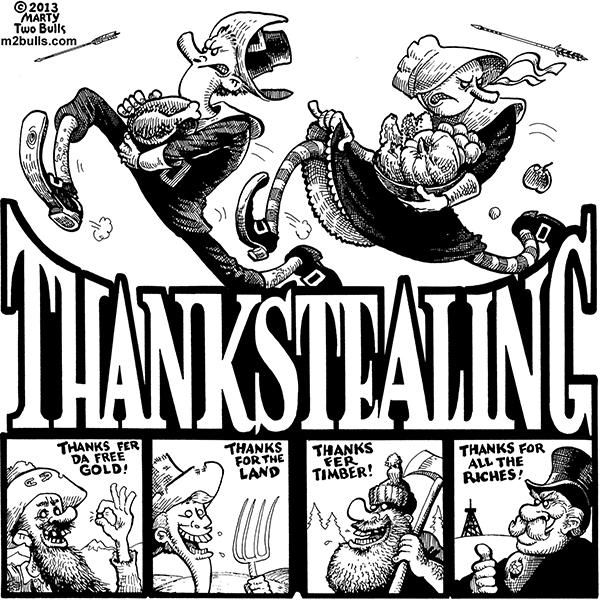

This splendid article is at Aeon, and the whole thing is well worth reading. There are hundreds of comments, too, if you feel like reading more. The questions posed by the loss of “what do you do” don’t puzzle me, or pose any problems. Well, they wouldn’t pose problems if we hadn’t been so busy getting much too big for our collective britches. The answer is what Indigenous people keep pointing to, and being ignored by the populations at large: community. When there is a community, all the people in it are invested, and everyone works, they all work to to sustain one another, to make their community a good one. Chores are shared, as are burdens, which makes them lighter. In our current societal pattern, when a person is unduly burdened, the general response of those around is to mutter some half-assed proverbial solace, then flee. There’s always a constant fear too, that if we extend ourselves by helping, we may not keep enough for ourselves, and soon find ourselves in a similar unduly burdened state, with nowhere to turn.

We came up with cities to accommodate industry, and their need for workers. Once the workers showed up, those with capital at their disposal began instilling a lust for goods, and propagating the ‘great story’ – if you just work hard enough, you can climb that social ladder! Too many people spend their lives in a state of unthinking misery, constantly on a treadmill of never being quite satisfied with what they have, it’s important to have more. To have better. What will the neighbours think? There’s gentrification, which does not embrace the richness of an area and find a way to make it work for everyone, no, it’s a way to drive all those people away, so it can be properly upscale, for the right sort of people.

A lot of people have enough – they have shelter, clothing, they can put food on the table, they can get around, they have books, internet access, television, all that. And yet, we are taught to not be content. Everything around us screams “if you can’t afford this, you suck!” If we are content with what we have, but don’t have x amount of income, and all the toys to show it off, we’re dumped into the “lower class” box and dismissed. We need community. We need to learn to share, we need to learn to care about the things which matter, not stuff which advertisers and manufacturers insist we must care about. It’s past time we figure out how to care for one another again, on more than one level.