The first moment where I started to wonder was in 6th or 7th grade social studies. We had a textbook about “geography” which included some geopolitics; a picture on one page of Uncle Sam sitting in a circle with characteristic (even stereotypical) kids of various ethnicities. It wasn’t quite as bad as that the kid from Africa had a bone through his nose – not quite. The caption read “Americans want to be friends with everyone.” And when the page was turned, the picture was of a Red Army soldier in WWII uniform, with a ppsh tommygun held at port arms, “The Soviets want to rule the world.”

For a while, I used to search on Ebay for that book, since I sometimes wonder if it was just my imagination. For a long time I couldn’t accept that my country – for I still believed at that time that it was my country – would lie to me so ineptly, and badly. It had been around that time that I hung out with Boris. Boris was the son of a visiting Russian (still Soviet) professor, and he was just like me. He wasn’t stronger or meaner or smarter or dumber – he was just a kid; we had to figure out a bit about how to communicate – mostly we were swinging on a rope hanging from a tree, so there wasn’t much need for language. But I never forgot that here was this Soviet kid just like me, no tommy gun, no jackboots, liked to play with swings, too. Another thing stuck in my mind: some of the other kids in school made fun of me for being a “Commie lover.” Little memories like that stay in our minds, like grains of sand in an oyster’s shell, irritating us and making us think around them to make them lose their sting.

Then there was the visit of one of my father’s colleagues from WissenschafteKolleg Zu Berlin, Axel Von Dem Bussche. I was a teen-ager when he came to Johns Hopkins for a while, and I learned a few things about him. One of the things I learned was that he was a Nazi, at one point. But then it got complicated; he wasn’t really a nazi, he was a German nationalist who wore the uniform – including an Iron Cross, Knight’s Cross, and more – but he was actually, literally, in the position of trying to assassinate Hitler with a suicide-bomb, but dumb luck interfered with his plans and Von Stauffenberg’s attempt changed the security around Hitler so that Axel’s personal plan became impractical. I remember talking with him – he was a huge man who walked with a limp and spoke with a parade-ground voice – still very much the Panzergrenadier – and he didn’t tell me those parts of the story. He laughed silently and gently when I said I was interested in psychology and philosophy, and said, “If you figure anything out, let me know.” He didn’t like to tell stories about the war, though he commanded a regiment at Kursk which was some fighting indeed. He said, “war destroys philosophy.” I remember him tipping his head and giving me a long, serious, look when he said that. I got some static for being a “Nazi lover.” But my brief encounter with that strange, thoughtful, man left me more nonplussed about politics and war than anything else, and tilted me toward doubting the utility of war.

“Morning at Passchendaele” – Frank Hurley

Doubting the utility of war has a tremendous corrosive effect on nationalism, because it’s impossible not to think about it and not to realize that it’s what nations do. Especially if you’re an American. I didn’t know much about Vietnam as a kid, except that most of the university professors were against it, so I was, too. Then there was the day when I snuck to the corner of the bookstore, where the Hustler Magazines were, and (in search of porn!) opened the issue where Larry Flynt decided to break a taboo by printing pictures from Vietnam that had not gone through the censors for approval. That was when I discovered that I sometimes faint at the sight of blood.

I joined the army in 1983 because I wanted to convert an enlistment bonus into a motorcycle, and, as an enthusiastic martial artist, I wanted to see what it was like. Really. I was that stupid. Then, I got a better view of the inside of the beast and realized that the whole thing was stupid. And that was when I started studying it from the inside, looking out, and put everything on the table and questioned it. I rolled my beliefs back to that geography textbook with the Red Army soldier, and re-constructed them forward. The hardening I felt in my heart and mind was cynicism – a deep, abiding, awareness that they don’t just lie to you: they always lie to you. And I began to read military history differently. Instead of reading stories of military glory, I started reading about colonial wars and imperial wars, and the great endless slaughter and stupidity that the powerful conjure up to consolidate or maintain their power a little longer. I read Halberstam and Hackworth, Sledge and Leckie, and Kogon and Gottlob, too. It dawned on me that military glory was a lie, that Smedley Butler – America’s own little military monster – was such a straight-out bastard that he told the truth for all to see: War is a Racket.

Somewhere around the age of 20, I was a thoroughgoing nihilist; not the stereotypical “kill the world!” sort that is caricatured in comics and movies, but rather a person who had developed a corrosive skepticism about every moral argument, political justification, or political ideology that served anyone except for the masses. I tried to crack Marx but, try as I might, I couldn’t help but feel that it was also a load of bloviation; Marx was simply offering a different form of dominance, as an alternative to the ruling form of dominance. I tried Mill, but I felt that it was too much hand-waving (I still do!) – then I read Robert Paul Wolff’s In Defense of Anarchism and it felt like some lights had come on: there were a lot of people who had concluded that nationalism and government were lies. I realized I was backing myself into a corner, mentally – I was perhaps coming to understand why that gentle German professor who once wore the Iron Cross had said, “If you figure anything out, let me know.”

George V and Czar Nicholas, cousins of the Kaiser – the upper class twits who blew up the world. Like all true chickenhawks, they loved the (unearned) trappings of military glory.

Military history (and UNIX kernel source code) remained my mainstay reading until I was browsing dad’s shelves and pulled down David S. Landes’ The Unbound Prometheus. When he saw me reading it a few days later, he cocked an eyebrow and said merely, “that is a great book.” What Landes teaches us, or what I learned from Landes, anyway, is that inequality in industrial output is just as much of a cause of wars as jingoistic nationalism. It was inevitable that once German industrial capacity rocketed off the chart, leaving everyone in the dust, it would occur to Germany’s rulers to use it for the purpose of aggrandizing the worthless remaining years of their lives – no matter the expense to everyone else. I studied World War I with new eyes, seeing it as a gigantic squabble between a bunch of dysfunctional elite twits (who were mostly cousins) – who killed millions, horribly, because of unequal industrial output, technological disparity, and sheer stubbornness.

I believe it’s impossible to really look at World War I and World War II and remain a nationalist, afterward. What we see, over and over, is that the power elites of all the nations involved, were not operating out of any kind of moral principles – they were barely doing things that made sense at all from their own national perspective – it is impossible to believe in the international system or the idea that the leaders of a country have anyone’s interest in mind but their own. All you have to do is watch Hitler making deals and betraying everyone, for what end? It ought to have been obvious that global conquest was not possible. It ought to have been obvious that the only result that could come from World War I and World War II was the United States Empire.

Again, my perspective began to shift; I started to look at the evolution of the US – not as a “democracy”, but as a new form of empire that the planet had never seen before. My little encounters with Marx and Mill and Landes made me see empire as an economic problem, not a military one. Somewhere around then, I whipped through Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and was rattled enough that I asked dad, “do historians have a consensus on Zinn?” Usually, when I ask my father questions about history, I do not feel the need to be oblique – I just reach out and turn on the knowledge-valve. This time, I signaled clearly that I only wanted a trickle. So he said, “Zinn is problematic but very important.” In other words, “If a trickle is what you want, a thimble-full is what you get.” I began bouncing all over the place, desperately: Thucydides, Gibbon, Tom Holland, Churchill, RAND Corporation studies on nuclear deterrence… I had always been interested in nuclear weapons as the marvels of engineering that they are, but I had never thought of them in the context of imperialism. I felt foolish, over and over, as what I saw were great chunks of puzzle falling together. And the puzzle said that politicians are shit, and civilization has been suborned by the rich and powerful to create a worldly playground for their endless stupidity. Civilization is, in fact, a creation of the rich and powerful; maintaining their place atop of the heap is the greatest ponzi scheme, ever.

That’s where I am, now. And, unfortunately, I don’t see disconfirmation at all. I constantly check myself for confirmation bias but under the shit, all I see is more shit. Let me wrap up with a sketched outline of the big puzzle-pieces I am currently jiggling around. There are two areas of the puzzle that interest me. First is the idea that the US is a new type of empire; it’s Imperial Capitalism. Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia were examples of Water Empires states in which the control of water flows equated to the flow of agriculture, which in turn equated to control over people. Like all forms of imperialism, it was simply that: a way of achieving vast leverage against a disproportionate number of people. The water empires fell (because, they were static and based on infrastructure) to the Smash-and-Grab Empires: Rome, the Mongols of Genghis Khan, empires that exploited disproportionate local military power to play a gigantic game of Whack-a-Mole with the map, running around crushing whatever power stood against them, successively, and grabbing their gold. Then there were the Mercantile Empires like France and England, which were the smash-and-grab with an attempt to build colonial assets into the imperial economy. The mercantile empires, naturally, relied on military force as much as they did negotiation – so the British managed to cobble together a vast empire that kind of worked, until they discovered that you cannot industrialize a vast empire fast enough to compete with a superior industrial power, and Europe punched itself in the face over and over again. The US is an evil new thing in the world – it’s a capitalist empire that uses smash-and-grab to kick open the doors to new markets; to force places around the world to build Starbucks’ franchises at bayonet-point, and the cash, the reason for it all, flows back to the greatest collection of consumers in the history of the Earth. American Imperial Capitalism will blow the crap out of a country to get good deals on natural resources, then sell them the tools they need to repair the damage, and it doesn’t care as long as its ruling elite can siphon their ‘vig’ off the top. Sometime around the reign of Theodore Roosevelt, the US’ leaders realized that it is not necessary to control a resource or a place; it is only necessary to have the means to bring it under control as necessary. In other words, there is no need for Hitlerian conquest and annexation; we simply get other nations to acknowledge that conquest is possible and therefore not necessary. That is what the nukes are for; they are the ultimate “poison pill” – if we kick over the table and storm out of the game, nobody else will ever get to play it, ever.

Thomas Jefferson, gadabout dirtbag

The second big puzzle-chunk I am trying to place is that apparently the capitalists that rule the US have always known this. I’m not ready to hoist the “conspiracy” banner, but it’s suspicious as hell that the oligarchs who founded the US [stderr] did it to protect their corrupt trade in human flesh. And, they constructed the new nation to preserve their personal power using that same trade as financial and political leverage [stderr] – as the US entered its industrial revolution, it rapidly outstripped Germany and England (by ruthlessly ripping off their technology) and proceeded to re-arrange its entire economy in order to prevent labor from ever having a say in what happens, again by dividing and conquering its own people along racial and class lines. The history of the depression, bonus army, Wall St Bombing, Battle of Homestead – those go back to the beginning, when Alexander Hamilton put the screws to the little guy in order to strengthen the government and larger businesses’ interests. That triggered the Whiskey Rebellion, which brought the United States its permanent, standing, domestic counter-insurgency capability.

It was one of the commentariat here who recommended The Whiskey Rebellion, and that was a great recommendation; it’s a border-piece, that delineates one of the early indicators of how Imperial Capitalism evolved. The oligarchs ruling the horrible new pimple adorning the face of the planet Earth, had realized that it’s not necessary to tightly control everything – it’s just necessary to be able to control things when necessary. And the easiest way to do that is to give the people you wish to control just enough to keep them happy – and don’t let them see how high on the hog the elites are living.

This year I am 54, and I hate America. I have come to loathe the United States and what it stands for, especially because I see that it has metastasized like a cancer into the world’s political economy. Imperial Capitalism has positioned itself so it cannot be rooted out without killing its host. It cannot even be slowed down without killing its host.

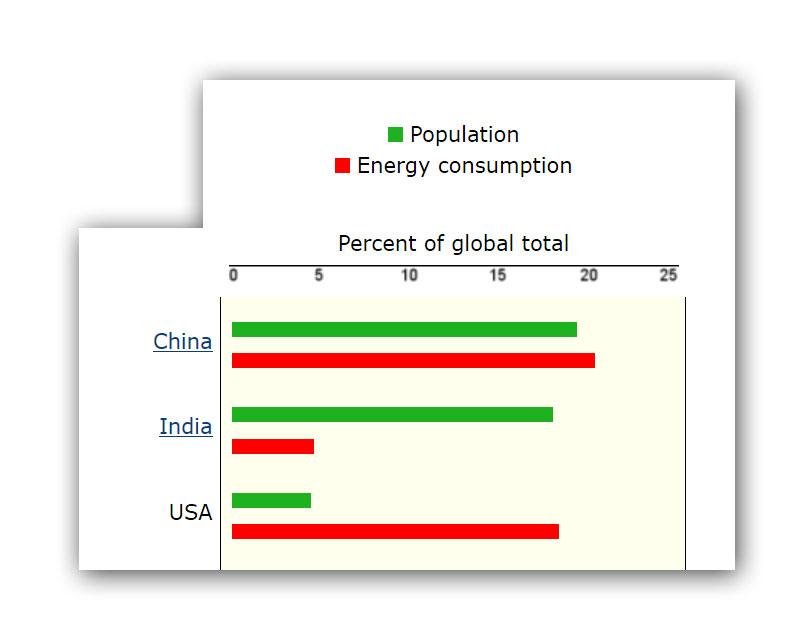

This chart tells me that the US is using almost as much energy as China, which has 1/4 of the world’s population. Another way of putting that is that the US is dominating global resource use even though it’s relatively small – i.e.: Imperial Capitalism has been working just great. Of course, it’s never early (or late) innings; nothing short of a nuclear war or massive ecological disaster is going to upset the game. The US is going to keep its boot on the world’s neck for a very long time – probably until it falls apart from its own internal stresses brought on by its own corruption and inequality.

Axel Von Dem Bussche [wikipedia]

“Massive ecological disaster” is already in the post.

Personally, I reckon the US has less than a century left as global hegemon. Your oligarchy has gone full-blown kleptocratic, for one thing, but more importantly, you’ve made the same mistake we Brits did, and which had already doomed our empire well before WWI: offshoring key bits of your economy.

The way modern empires start out is by funneling raw materials from the periphery to the center, where they are made into finished products which are then re-exported. This sets up a very effective mechanism for pumping wealth to the manufacturing centers – wealth that can then be re-invested in better production equipment, or military capacity to expand the empire, bringing in new sources of raw materials and opening up new export markets, and so on – it’s a self-sustaining cycle.

However, eventually the law of diminishing returns starts to kick in, and the returns on those sorts of investments starts to drop. At this point, some bright spark realises that they can get a return by off-shoring some of that production capacity and taking advantage of the (now massive) wage disparity between the imperial center and the periphery. This is great for investors and consumers in the imperial center, as it gives the former good returns, and the latter cheap goods. However, it begins to reverse the flow of wealth, as the productive capacity at the imperial center is hollowed out, and the value added in production is increasingly retained in what used to be the periphery. At this point, the demise of the empire is assured.

For Britain, the key was the transfer of our textile industry from the north of England to India. For the US, the process is now well-advanced in all industries.

The capitalist empire is falling as we speak. There might have been a way to shift sideways, to make the fall a more gentle one, but that opportunity is gone now. The whole mess worked for a while, when industry ruled here, and it was possible for people to build a decent life. That’s long gone, because the few assholes with all the money just can’t stand to spare a cent, so there isn’t any industry here anymore. It’s all gone elsewhere.

Now, as everything is falling, those with money, or at least their hands in the pockets of the monied, are out to grab what they can before they bail. There’s not even any pretending anymore.

Dunc@#1 and Caine@#2:

What I’m afraid is going to happen is we’re going to wind up with a metastasized supernational class of ultrawealthy parasites. In a sense, that process began with the French revolution, when the ci-devant took their money and ran. And the Russian aristocracy took their money and ran. And the various scumbag tin pot dictators of the world take their money and run.

Perhaps when it all sinks in that humanity has been ripped off, the people will hunt them down and guillotine them. Or perhaps they will burn the world down around them rather than give up their ill-gotten gains.

There are two other pieces I didn’t mention (because I was already weaving badly in and out of the weeds…) which is prosperity gospel and capitalist democracy. The robber barons of the early 20th – the Carnegies and Fricks and Mellons – promoted a weird fusion of social darwinism and laissez-faire capitalism, with a hint of calvinism stirred in. It’s impossible now to know if they believed it (they probably did) but folks like Carnegie went all-out to propagandize the white working class with the idea that “if you just work hard, you too can be a millionaire!” The pernicious American ideology that enthralls capitalism’s renfields, like Bonaparte’s claim that every French soldier had a marshal’s baton in his rucksack, if he just chose to reach for it. Like everything else about America it’s a lie – the road to prosperity is inherited wealth and opportunity.

All these pieces of the puzzle are on the table and I keep rearranging them and looking at where they fit and all I see is ugliness.

(Edit: I have some more stuff coming from Richard Hofstadter, which puts a few more of the edge-pieces into place)

Dunc@#1:

The way modern empires start out is by funneling raw materials from the periphery to the center, where they are made into finished products which are then re-exported. This sets up a very effective mechanism for pumping wealth to the manufacturing centers – wealth that can then be re-invested in better production equipment, or military capacity to expand the empire, bringing in new sources of raw materials and opening up new export markets, and so on – it’s a self-sustaining cycle.

Yes!

#1 Dunc

Personally, I reckon the US has less than a century left as global hegemon.

Personally, I’d say it is just about over unless we are talking nuclear war to maintain its position

The US has outsourced so much of its industrial output and seems to be adopting such mad social policies that a very fast decline seems almost inevitable.

If nothing else, the current US administration seems determined to a) destroy its educational system and b) alienate just about every country in the world over its stand on global warming.

I suspect that many of its allies way be rethinking their position. Angela Merkel’s comments were not a fulsome endorsement of the US alliance and to be honest, if I were South Korean, at the moment, I would regard the USA as more of a danger than North Korea.

For Britain, the key was the transfer of our textile industry from the north of England to India.

I had not realised this had happened.

Can you give me a couple of quick references on this? I had always thought that Britain had not suffered a more precipitous decline was due to very little outsourcing but I can see how that would devastate things.

jrkrideau:

It wasn’t long ago, on this blog, that Dunc and I opined the loss of the great British needle. For centuries, the finest needles in the world were considered to be English, but that honour is gone, as the last of the British needlemakers were swallowed up, and none of the needles are made in England anymore. A lot of people didn’t realize this, as the ‘Made In Britain’ was quietly disappeared off packets. It’s all Entaco now.

Now, I strictly buy Bohin out of France.

Caine@#7:

Sheffield steel used to be The Shit. Then it was Solingen steel.

Pittsburgh, which used to produce more steel than all of the rest of the world combined, has gone cold – there is no steel production at all, anymore. Altoona, which was the American equivalent of the Ruhr, has one little machine shop left that makes train parts for hobbyists. There is one hot metal foundry still in Clearfield, which makes a cannon or two for civil war reenactors.

Now it’s Shenzen CNC and Swedish powdered castings.

I believe what Dunc is referring to is that American cotton production, which used to be one of the US’ big contributions to the British empire, got shipped to Madras where it was cheaper to spin and produce – the British basically cut themselves out of a crucial part of their economy and maintained their position as “middleman.” That’s great until someone comes along and cuts out the middleman.

What happens to Apple when Foxconn decides to make a cell phone?

@6: Sorry, it’s one of those things that I sort of picked up by osmosis over the years… But yes, the gist is as Marcus puts it @8. The entire cotton spinning and weaving industry for the world used to be located in northern England, but eventually got relocated to India. The resulting economic and social development was, I believe, an important factor in the push for Indian independence.

Also: The US decline certainly could be quite rapid, but I wouldn’t bet on it – empires have a lot of inertia. I am, however, bearish on US investments, and bullish on Indian and Chinese investments. Certainly, I expect the decline of the US empire to be fairly rapid by world-historical standards. A century would be my outside bet.

@Dunc #10:

There are several things that make me think the the decline is well under way.

First, the level of homelessness I witness daily in the centre of San Jose that bills itself as the capital of Silicon Valley.

Second: Articles like this: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/sanitation-open-sewers-black-belt_us_5a33baf5e4b040881be99da5

I see efforts to try to halt the decline, but I’m not confident that these will be successful.

@Marcus, #8:

I would change that to “market a cell phone” – they already make them.

Sunday Afternoon@#11:

I would change that to “market a cell phone” – they already make them.

Good point.

Working in information security, I often encounter the dying moans of nationalists, “the Chinese are stealing our intellectual property” being one of them. Usually I sneer at them and say, “I have news for you: Apple taught Foxconn how to make iPhones.”

One of the koan I used to occasionally throw out was this:

Q: “How do you steal intellectual property from a capitalist?”

A: “In the boardroom.”

It seems a bit simplistic to equate Egypt and Mesopotamia, particularly in terms of centralised control of agriculture. The two regions differed markedly in antiquity as far as farming and water supply were concerned. Mesopotamia was comparatively dry and arid, and to farm it successfully on a large scale required complex irrigation systems and the associated centralised control. Egypt, by contrast, was naturally fertile thanks to the overflowing of the Nile. You didn’t need irrigation on anything like the same scale – independent farmers could just bank up their own fields to trap the fertile Nile mud and then get on by themselves. Which is part of the reason Egypt was never really an Imperial power, never really a big slave-owning society, and had considerably greater social equality than its neighbours to the north. It experimented with oppression on its borders, but Egyptian society and culture was so focused on the Nile and its unique agrarian bounty that it really didn’t travel very far beyond.

The Roman Empire can be seen in terms of opportunistic smash and grab military imbalances I suppose. At least as far as the early centuries in which it was acquired are concerned. In many ways the origins of the Empire are to be found in the ubiquitous patterns of endemic cattle-raiding warfare that pretty much all ancient cities indulged in. Rome just happened to have the peculiar notion that, rather than simply carry off slaves and cattle when you do a neighbouring city over, it is more profitable for all concerned if you impose tax obligations and recruit more soldiers from your conquered foes. The driver was aristocratic competition and status-seeking, but whereas the traditional Homeric concept of heroic achievement stops at plunder, reputation and demonstrating your excellence, the Romans placed just as much significance on dignitas and auctoritas – being masterful and being obeyed. The very word from which our “empire” derives – imperium – hints at this concept. It means “command” or “ordering” – it’s not about painting the map in your colours or controlling the resources, it’s about being the one whom everyone else will obey when you give the orders. Roman tomb inscriptions from as early as 300BC are redolent with this concept of aristocratic achievement, and it became ever more central to the established Roman families vying with each other throughout the last centuries of the Republic.

Things changed with the establishment of the Principate and the dissolution of the old Republican order. Romans were forced to confront the link between their Empire and the inadequacy of their traditional political system in the face of runaway military adventurism. They were also forced to justify their position as Imperial hegemon for the first time, and think through what it said about their role in the wider world. In short they were forced to come up with an explicit philosophy of Empire, rather than just sitting back and enjoying the runaway success at cattle raiding that got them where they now were. Perhaps the most succinct encapsulation of this explicit imperialism comes in Anchises’ prophecy to the as-yet unborn Romans in Vergil’s Aeneid book 6 –

“And you, Roman, be mindful to rule the peoples of the world by command,

for these shall be your arts: to impose the customs of peace,

to spare the vanquished, and to war down the proud”

Roman imperialists began to think of themselves as the ones tasked by fate with the special duty to maintain peace in the world, so that everyone else could live freely and practice their special arts – science, music, sculpture, trade – whatever it was that Greeks and Barbarians did to beautify the world the Romans had secured for them. Later Emperors took it even further – Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli speaks of a high-minded programme of cultural exchange and artistic patronage that was the direct product of the Pax Romana. To Hadrian the Empire was a well-regulated cultural melting pot in which the excellence of art and literature and religion could be protected and promoted as it achieved ever greater heights. Barbarians could be inducted into the benefits of culture, trade would enrich everyone, all would be well.

It is easy to see all this as high-minded propaganda, or genteel naiveté on the part of an out of touch emperor. But it does coincide with radical changes in how the Empire was managed and administered. Yes, there were still occasional conquests (Dacia being the most prominent), but the Imperial system became more about protecting trade routes, connecting far-flung cities with roads and creating a stable system of currency. One very important economic factor in driving all this was the rampant growth of the city of Rome itself – its population had long since outgrown the ability of Italy to support it with its agricultural surpluses, and a steady supply of food, luxury goods and wealth was needed to keep the people quiescent. This later, mature, phase of Empire is perhaps the most direct model for Early Modern European imperialism, and modern American imperialism after it. Admittedly without the worst excesses that modern capitalism has conjured. And I say model quite specifically – the shadow of Rome was at the forefront of the breakaway nation-builders of the colonial aristocracy. America was conceived of as a nascent Imperial power from the beginning.

Thank you for posting this.

cartomancer@#13:

It was with some trepidation that I threw the “Water Empires” bit out there. Obviously, there was a lot of over-simplification going to be required to make some of the connections I was going for. It’s completely reasonable, to me, to reject those connections but it’s my opinion that there’s something there. Empires have constituted themselves and maintained themselves differently, and that’s important. On the other hand, what I completely didn’t touch upon is your point, which is that empires change into a “maintenance mode” once they stop growing, and their practices change as well. I didn’t take that into account, and I’m not sure I can get away with saying something like “at the scale I’m looking at…” and I won’t try.

The very word from which our “empire” derives – imperium – hints at this concept. It means “command” or “ordering” – it’s not about painting the map in your colours or controlling the resources, it’s about being the one whom everyone else will obey when you give the orders.

How …. Trumpian.

Unrelated, have you read the First Man in Rome and The Grass Crown or some of the other books by Colleen McCullough? I read them and loved them but wondered whether they were reasonably fair portrayals of Rome at the time, or not. It must be daunting for a writer to set a novel in a time that is both so well-documented and so distant.

Roman imperialists began to think of themselves as the ones tasked by fate with the special duty to maintain peace in the world, so that everyone else could live freely and practice their special arts – science, music, sculpture, trade – whatever it was that Greeks and Barbarians did to beautify the world the Romans had secured for them.

That sounds eerily familiar. The British seemed to also consider themselves the great civilization-bringers (even if it came in the form of a bunch of Martini-Henry rifles…) and the Americans, in their turn. “The world’s police” – ugh, I hate that phrase – but it beats “white man’s burden.”

America was conceived of as a nascent Imperial power from the beginning.

Another important point. There has always been a lot of dancing around that fact, but it remains there.

I used to imagine that there’s a Presidents’ Book which is the secret plan of the presidents of the USA – Washington and Jefferson’s notes for how to build a fake democracy and slowly parlay it into global domination. Sort of like a rotten version of Hari Seldon’s future history from Foundation. Of course we can now be sure that there is no Grand Strategic Plan, because if there were, Trump would have tweeted it out immediately.

The caption read “Americans want to be friends with everyone.” And when the page was turned, the picture was of a Red Army soldier in WWII uniform, with a ppsh tommygun held at port arms, “The Soviets want to rule the world.”

My experience was very similar. School tried really hard to teach me patriotism. I was forced to sing nationalist songs, read literature glorifying war heroes and so on. Basically all the same crap you experienced. And by the time I was in my teens I slowly realized that all this crap was wrong. The emphasis of that patriotic education was to convince me that the country I lived in was, to quote Voltaire’s Candide, “the best of all possible worlds.” I was taught to be happy that history turned out the way it did, I was taught about the horrors of the Soviet regime and told that my life would have been miserable if historical events had happened differently. It seems to me like every single country attempts to justify itself by indoctrinating its citizens (especially kids) into believing that the country they currently happen to live in is the best possible option.

It had been around that time that I hung out with Boris.

Yes, it was the same for me, actually hanging out with Russians who were nice people convinced me that all this nationalism was just plain wrong.

I tried to crack Marx but, try as I might, I couldn’t help but feel that it was also a load of bloviation

I tried reading Marx and never got beyond the first 50 or so pages. Arguments and explanations were unbearably long, and the author took countless pages to explain a point that could have been said in a few sentences. I ended up getting a summary.

That photo of George V and Czar Nicholas reminds me of Soviet jokes about Brezhnev’s love for medals. I have heard several of those; one of my favorites goes as follows:

“Did you hear that Brezhnev survived an assassination attempt yesterday? His medals shielded him.”

“But I heard the assassin shot him for five minutes with a machine gun.”

“What is your point?”

Somehow murderous monsters seem to love sticking lots of metal on their chests.

This year I am 54, and I hate America.

I started hating my country when I was 23. My main reasons were different. It started with misogynistic nationalists telling me that I’m just a uterus, that I have a duty to make babies for the sake of the country. For them my own desires, my own life didn’t matter; all that mattered were the babies I should produce. Later my hatred for the damn country grew even larger when I came out of the closet and I started dealing with homophobes. The kinder ones told me to emigrate, the less kind ones told me to die and burn in hell. Of course, I also don’t like all the politics that’s going on in the country, so that’s yet another reason.

And I also hate USA. If Americans only made their own lives miserable, I could choose not to care (that’s none of my business how other people choose to live their lives), but Americans are trashing the whole planet, thus, unfortunately, it does concern me.

WissenschafteKolleg Zu Berlin

It’s “Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin.” In German you don’t use capitals for prepositions (like “zu”) or in the middle of compound words. And there’s an “s” letter in the middle of the word, because there’s a Genitive case.

That sounds eerily familiar. The British seemed to also consider themselves the great civilization-bringers (even if it came in the form of a bunch of Martini-Henry rifles…) and the Americans, in their turn. “The world’s police” – ugh, I hate that phrase – but it beats “white man’s burden.”

Of course it sounds familiar. Whenever a group of people try to invade some other place, they claim that it’s being done for the conquered people’s own benefit. Christians were saving pagan souls from hell. Soviets claimed that it was their burden and duty to liberate the poor and oppressed working classes from the evil capitalists.

Ieva Skrebele:

Ahem. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dum_Diversas

(You think the term conquistadores refers to missionaries?

Nah. Those came later, for proper subjugation)

Marcus, #15,

I have read The Grass Crown, and a couple of other Rome-based historical novels (Gore Vidal’s Julian springs to mind). They’re generally pretty good with specific historical details that we know, and not too bad with overall cultural attitudes, but there are a great many things we simply don’t know about day to day life even in relatively well-documented periods of ancient history.

As such the accuracy of anyone’s reconstruction is open to doubt. For example, we know a fair bit about the layout and furniture found in Roman houses, thanks to the discoveries at Pompeii, but we have very little idea just how many people would be living and working in these houses on a day to day basis. 19th century archaeologists and historians tended to assume that the typical grand atrium-peristyle type house was very much akin to a 19th century aristocrat’s well-appointed townhouse, and might be home to a bachelor and a couple of servants or a nuclear family at most. Recent archaeologists have challenged that view, citing finds of large numbers of spinning distaffs and other textile-making equipment in the atria of a few such houses to claim that perhaps these homes were packed with 20 or 30 slaves doing weaving work much of the time, like little Roman sweat shops, and at night those slaves would bed down on the floor. It’s a salutary lesson against just projecting our own lives back onto the Roman evidence, but is the new “very much not like our world” picture of the Roman townhouse any more accurate than the 19th century “very much like our world” one? The literary sources give us very little to go on, so we’re left sifting through the archaeology and guessing. Might those spindles just have been stored in the atrium when the city was destroyed, ready to send on to a shop or warehouse? Might there not have been a typical Roman, or even Pompeian, protocol for home space usage at all?

As far as historical novels go, I tend to just let the author fill in these gaps how they will and chalk any misunderstandings up to the mists of time. If they want Romans living like cloistered away 19th century aristocrats then fair enough – it might have happened on a large scale and almost certainly happened somewhere. If they want grand homes packed with light industry instead then that too is possible. In a way the fact we don’t know every detail makes it easier to write about these periods. Were I reading a novel set in England in the early 1990s then I would be much more likely to pick up on egregious mistakes, but when there is nobody who knows exactly how everything was there is greater freedom to improvise.

@ 8 Dunc

Thanks

cartomancer@#18:

Thank you for (as always) the illumination.

It’s so interesting to realize that this was a civilization that was so important to the world, yet there are big gaps in our knowledge of the day-to-day stuff. Presumably because they didn’t bother to record anything about it, since it was just “how things are done.” An anthropologist could figure out a lot about early 21st-C life just from Facebook and instagram. But there would still be things they’d miss because we’d just expect everyone to understand it all. I guess now there are so many byproducts – manuals, assembly instructions, etc., it’d be possible to piece it all together.

Except the finger-spinners. I’m pretty sure future archeologists will wonder what the hell those things were for. So do we!

None of that stuff is likely to be well-preserved in the archaeological record though… As for all of the digital media, we’ve already lost a bunch of stuff from the late 90s / early 2000s because of data format obsolescence.

I’m pretty sure that from a historical or archaeological perspective, we’re entering a new dark age, because despite the fact that we’re producing more records than ever before, virtually all of it is extremely ephemeral. For example, back in my days in the civil service, I remember noticing that the quality of record-keeping took a nose-dive with the introduction of the fax machine, because early faxes used a thermal printing process that wasn’t stable for more than a few years – with the result that we had meticulously indexed files full of blank paper. I strongly suspect that with the exception of some extremely rare cases of accidental preservation, virtually all of our printed materials will be illegible in a matter of centuries at most.

(Mediaeval historians are extraordinarily lucky that the combination of oak-gall ink on vellum happens to be remarkably stable, provided you keep it dry.)

John Morales @#17

I was referring to Northern Crusades of 12th and 13th centuries. Theoretically the goal of these crusades was to convert pagans to Christianity. It just so happened that a nice side effect of this selfless and pious endeavor happened to be an opportunity for conquerors to enrich themselves.

There was a book I read some years back, which I found a bit odd at the time, and then only years later realised how cynical I should have been about it.

The book was a collection of (Australian Aboriginal) Dreaming stories, as retold by an Anglican chaplain from a mission school. I recognised a few of the stories – but also that new elements had been added into them from the versions of these stories that I had previously encountered – ideas resembling an initial state of grace, a fall from grace, and the need for sacrifice to restore grace.

It was somewhat later that I put things together. Children would be removed (“for their own benefit”, naturally) from their families and communities and taken to these mission schools. There their pastors taught them the same stories their parents and Elders had told them – but with the necessary mythological background for Christianity embedded into them. Now they understood the need for salvation to restore grace – and waddaya know – the Anglican ministers conveniently had some salvation to offer.

Myths are important. It’s something that Tolkien understood as he endeavoured to craft a mythology suitable for Catholic Britons (a substantially more honest undertaking than that of the missionary above). And of course Americans are very rich in their self-mythologisation.

I have a strong tendency towards gloomy passivity. Ugh. I agree with so much of this discussion. Luckily, I am your age and not all that healthy, so…

bmiller@#24:

Luckily, I am your age and not all that healthy, so…

Fly below the radar and run the clock out, eh?

Ieva Skrebele@#22:

It just so happened that a nice side effect of this selfless and pious endeavor happened to be an opportunity for conquerors to enrich themselves.

It also gave those who wanted to stay behind a perfect way of getting rid of young, aggressive, warlords. “Go off on the crusade…. (waves) We’ll be waiting here for your news. Take your time. Really.”

Joel@#23:

It was somewhat later that I put things together. Children would be removed (“for their own benefit”, naturally) from their families and communities and taken to these mission schools. There their pastors taught them the same stories their parents and Elders had told them – but with the necessary mythological background for Christianity embedded into them. Now they understood the need for salvation to restore grace – and waddaya know – the Anglican ministers conveniently had some salvation to offer.

Christian missionaries pulled the same trick in China, Africa, … basically, everywhere. They absorbed enough of local legend structure as they had to, in order to turn it into delivery-vehicles for their lies.

There were christian (natch!) schools in the US that were predicated on raising native american children so that they were primed to accept white supremacy, er, culture. The stories of those efforts are heartwrenching.

Yet, at the same time, civilization has its…benefits. Were the “traditional” hunting and gathering clans that much better? Given that human beings are social animals prone to hierarchy, has there ever been a human social group that does not have the us versus them, hierarchy, and violence?

bmiller #28

Given by who(m)?

Chigau: Why by YAHWEH, of course!

In all seriousness, “given that” does not mean “given by”. It’s merely a statement that human nature, generally speaking, seems to have evolved with certain characteristics, including hierarchy. You might argue we can transcend this, or find examples where this is not true, but that does not mean that it is not a good general, vague, statement of the nature of human societies???

Even societies that have not evolved traditional states have “village elders” or “chiefs” or “shamans”. And they can act in nasty ways, just like “states” (my favorite was the Pakistani village council which decreed that because a boy had dallied with a girl of a higher caste, his sister was to be raped by all the males in the village).

bmiller@#28:

Were the “traditional” hunting and gathering clans that much better? Given that human beings are social animals prone to hierarchy, has there ever been a human social group that does not have the us versus them, hierarchy, and violence?

I expect traditional hunter/gathering clans probably also had a parasitic upper class, whether it was proto-politicians or proto-priesthood. Of course that’s just my cynicism making a guess; I doubt we’ll ever know. In my dark moments, though, I feel convinced that civilization co-evolved with authoritarian politics – the need to have surplus in order to support the parasite-rulers encouraged optimization of production, which resulted in more parasite-rulers (lather, rinse, repeat)

I don’t necessarily think it’s a “given” (i.e.: certainty) that humans will develop hierarchies, however it seems that it’s the default behavior. The question, to me, is whether that’s a side-effect of how power is aggregated and used, or an expression of human nature. Given how flexible human minds appear to be, I optimistically assume that it’s a learned behavior (not a “given”) and that humans could learn different ways of structuring power relationships in civilizations. Barring that assumption, I think we’re doomed as a species.

Of course that’s just my cynicism making a guess; I doubt we’ll ever know.

We can know this. There are still some hunter gatherer societies on this planet (OK, they are perishing quickly and the few remaining ones generally live deep in the jungle) and it is possible for anthropologists to observe how people in such societies live. From what I can still remember, I think that these societies had hierarchy and a somewhat parasitic “upper class”. Although I haven’t read enough anthropology textbooks to make any definite claims about this.

The question, to me, is whether that’s a side-effect of how power is aggregated and used, or an expression of human nature. Given how flexible human minds appear to be, I optimistically assume that it’s a learned behavior (not a “given”) and that humans could learn different ways of structuring power relationships in civilizations.

I’m more pessimistic here. Non-human primates have pretty nasty hierarchical structures. Some are worse (like chimpanzees), others are better (like bonobos), but they all have hierarchies. Animals, which live in groups, generally tend to have hierarchies. This is especially true for species, which need to organize collective hunts. The lazy male lion, which does not hunt but takes the prey from lionesses, eats first and takes the lion share, probably is the best known example. Even my mother’s pet dogs have a hierarchy among themselves — some dogs are the first to get food and they won’t allow other dogs to approach the food bowl until they have finished eating.

I’d say that hierarchical structures are close to inevitable. However, given the flexibility of human mind, I’m willing to maintain at least a bit of hope. When humans really want to abolish hierarchy and actually start working in order to achieve that, it can be done. Historically families were patriarchal (father on top of the hierarchy and solely responsible for all decisions), nowadays there are families where everybody is equal and eligible to participate in a decision making process that involves negotiating and making compromises. I’m also aware of some businesses, which forego the traditional “a boss on top” model and instead try to do something different.

And then there’s also the problem with unwritten hierarchies. Even in places where everybody is supposed to be equal, more experienced people with an impressive enough reputation are viewed differently than newcomers.

It shows.