Stanislaw Lem wrote some very witty and unusual science fiction. If you haven’t read Tales Of Pirx The Pilot [amazon] or Memoirs Found In A Bathtub [amazon] you might enjoy them if you like quirky and thoughtful fiction.

Tales of Pirx The Pilot has one of the most memorable scenes in science fiction: Pirx, an astronaut in a space mishap, has to spend a prolonged period in his space suit – and discovers that there is a fly in his helmet.

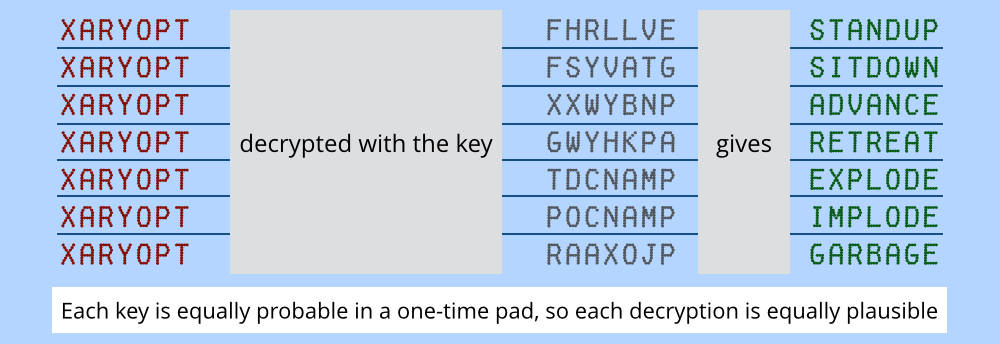

[source] (this is a pretty cool article if you’re interested in one time pads)

“Mr. Prandtl from the Department of Codes?” I asked, getting up.

“Except that I’m a captain. Remain seated. Interested in codes, eh?”

The last syllable was aimed like a shot between my eyes.

“Yes, Captain.”

“Don’t call me Captain. Coffee?”

“Please.”

The small black door swung open and a hand placed a tray with two cups of coffee before us. Prandtl put on his glasses and his features froze into a hard, fierce expression.

“Define code,” he snapped like a hammer on metal.

“Code is a system of signs which can be translated into ordinary language with the help of a key.”

“The smell of a rose — code or not?”

“Not a code, because it is not a sign for anything; it is merely itself, a smell. Only if it were used to signify something else could we consider it a code.”

I was glad of this opportunity to demonstrate my ability to think logically. The fat officer leaned over in my direction until his buttons began to pop. I ignored him. Prandtl took off his glasses and smiled.

“The rose, does it smell just because, or for a reason?”

“It attracts bees with its smell, the bees pollinate it. . .”

He nodded.

“Precisely. Now let’s generalize. The eye converts a light wave into a neural code, which the brain must decipher. And the light wave, from where does it come? A lamp? A star? That information lies in its structure; it can be read.”

“But that’s not a code,” I interrupted. “A star or a lamp doesn’t attempt to conceal information, which is the whole purpose of a code.”

“Oh?”

“Obviously! It all depends on the intention of the sender.”

I reached for my coffee. A fly was floating in it. Had the fat officer planted it there? I glanced at him: he was picking his nose. I fished the fly out with my spoon and let it drop on the saucer. It clinked — metal, sure enough.

“The intention?” Prandtl put on his glasses. The fat officer (I was keeping an eye on him) began to

rummage through his pockets, wheezing so violently that his face moved like a bunch of balloons. It was revolting.

“Take a light wave,” Prandtl continued, “emitted by a star. What kind of star? Big or little? Hot or cold? What’s its history, its future, its chemical composition? Can we or can we not tell all this from its light?”

“We can, with the proper know-how.”

“And the proper know-how?”

“Yes?”

“That’s the key, isn’t it?”

“Still,” I said carefully, “light is not code.”

“It isn’t?”

“The information it carries wasn’t hidden there. And besides, using your argument, we’d have to

conclude that everything is code.”

“And so it is, absolutely everything. Code or camouflage. Yourself included.”

“You’re joking.”

“Not at all.”

“I’m a code?”

“Or a camouflage. Every code is a camouflage, not every camouflage is a code.”

“Perhaps,” I said, following it through, “if you are thinking about genetics, heredity, those programs of ourselves we carry around in every cell. . . In that way I am a code for my progeny, my descendants. But camouflage? What would I have to do with camouflage.”

“You,” Prandtl replied drily, “are not in my jurisdiction.”

He went over to the small black door. A hand appeared with a piece of paper, which he turned over to me.

“THREAT OUTFLANKING MANEUVER STOP,” it read, “REINFORCEMENTS SECTOR

SEVEN NINE FOUR HUNDRED THIRTY-ONE STOP QUARTERMASTER SEVENTH

OPERATIONAL GROUP GANZMIRST COL DIPL STOP.”

I looked up — another fly was floating in my coffee. The fat officer yawned.

“Well?” asked Prandtl. His voice seemed far away. I pulled myself together.

“A telegram, a deciphered telegram.”

“No. It’s in code, we have yet to crack it.”

“But it looks like –”

“Camouflage,” he said. “They used to camouflage codes as innocent information, private letters, poems, etc. Now each side tires to make the other believe that the message isn’t coded at all. You follow?”

“I guess.”

“Now here’s the test run through our D.E.C. machine.”

He went back to the small black door, pulled a piece of paper from the fingers there and gave it to me.

“BABIRUSANTOSITORY IMPECLANCYBILLISTIC MATOTEOSIS AIN’T

CATACYPTICALLY AMBREGATORY NOR PHAROGRANTOGRAPHICALLY

OSCILLUMPTUOUS BY RETROVECTACALCIPHICATION NEITHER,” I read and stared at

him.

“That’s deciphered?”

He smiled tolerantly.

“The second stage,” he explained. “The code was designed to yield gibberish upon any attempt to crack it. This is to convince us that the telegram wasn’t coded in the first place, that the original message can be taken at face value.”

“But it can’t?” he nodded.

“Watch. I’ll run it through again.”

A piece of paper dropped from the hand in the small black door. Something red moved around inside.

But Prandtl got in the way so I couldn’t see. I picked up the paper — it was still warm, either from the hand or from the machine.

“ABRUPTIVE CELERATION OF ALL DERVISHES CARRYING BIBUGGISH PYRITES VIA

TURMAND HIGHLY RECOMMENDED.”

That was the text. I shook my head.

“Now what?” I asked.

“The machine has done what it can. Now we take over.” And he yelled, “Kruuh!”

“Huh?” the fat officer groaned, suddenly jolted from his stupor. He turned his bleary eyes to Prandtl.

Prandtl bellowed:

“Abruptive celeration!”

“Therrr. . .” croaked the fat officer.

“All dervishes!”

“Weeee! Beeee!” he bleated.

“Bibuggish pyrites!”

“Naaaa! Waaaa!”

“Turmand!”

“Saa. . . serr. . .” Saliva trickled down his chin. “Waa. . . wan. . . serr. . . rrr. . . Grr! Growl! Ho ho ho! Ha ha ha!” He broke into wild laughter which ended in a fit of horrible gurgling The face turned deep purple, tears streamed down his cheeks and jowls, the massive body was racked with sobs.

“Enough, Kruuh! Enough!!” yelled Prandtl. “An error,” he said, turning to me. “False association. But you still heard the entire text.”

“Text? What text?”

“There will be no answer.”

The fat officer sat back in his chair, trembling. Little by little he quieted down and, moaning softly to himself, caressed his face with both hands, as if to comfort it.

Google salutes Lem [more]

Someone at a writers’ workshop allegedly asked Lem whether the “D.E.C.” was a reference to “DEC” (Digital Equipment Corp) a computer systems company that was at its height in 1973 when the book was written – Lem said it was. I first read the book when I was in high school, my then-girlfriend R. being on a big Lem binge. I still find it funny that, a few years later, I was working for DEC and writing software for key management and authentication.

I coined the term “rubber hose cryptanalysis” back in the early 90s crypto-wars (Clipper chip and all that) and was thinking of the story above the whole time – the obvious next step for Prandtl would be to used “enhanced interrogation” wouldn’t it? Imagine trying to convince someone you were innocent, if they kept coming up with one-time pad keys that decrypted tantalizing but suspicious bits of your hard drive…. Now imagine if Department of Homeland Security was doing it. Not so funny, is it?

My shorter version?: “one time pads w/ real random chrtr gen is the shit” AND “fuck computers” = old school.

do the random gen w/ dice (10 dice, rolled and sorted as 5 groups of 2 ‘IN ORDER and translated into binary (from snake eyes to boxcars)’ gives you 36 characters which is a – z and 0 – 9.) Use a protractor to make code wheel, a different letter or number every 10 degrees: make 2 wheels, inner and outer with the letter/number assigns be the same order inner and outer. cut them out with scissors. put the smaller inner wheel on top of the larger outer wheel, putting a tack in from the center hole of each wheel into a wine cork.

This gives you the ability to add or subtract clear text w/ random mix w/ output code directly – without translating into numbers, and on the fly – without having to keep track of ‘carries’ and ‘borrows’. Less notes/calculations. DIY. Easy to burn.

Do OTP generation, code and decode manually – maybe use a confuser to send msg from here to there, maybe not.

I devised a contraption made of manila file stock, tape, and staples that will (more or less – you usually gotta tap things into place but you can do it blind without seeing what comes out) sort a cupful of 10 shaken dice into 5 ordered groups of 2 dice which equals a genuine random (by capitalist casino operators standards) 5 letter/number group per shake-and-throw. I’ll try to get it precisely measured and drawn out, w/assy instructions soonest.

Whee! A bottle of yer fave + a store pak of dice = drunken one-time-pad rolling sessions!

sillybill@#1:

That sounds pretty cool!

Some of us periodically talk about making a message-block:a lucite-block with a computer in it and a small display and camera: it can read QR codes with the camera and will decrypt them as messages against an OTP memory in the block. Blocks are paired and self-wipe as they use up the pad. The nice part about having the camera is you can use the “point this at a lavalamp or highway” trick to sample randomness.

I like the old-schoolosity of using dice, but rolling a terabyte worth of dice would take a while…

I have also pondered an art project OTP device that has the main board and memory (probably a pi) perched atop a shotgun shell with a relay controller that will wipe ‘with extreme prejudice’ the memory any time the device is moved without a certain QR code being flashed at it within 120 seconds. Run!

Cool story. It reminded me of an episode of Firefly in which a letter from Sim Tam’s sister is filled with missleppings and erroneous details. Simon concluded that this was a coded way for River to subtly scream “help!” The encoded message is in the plaintext message, and it takes someone who knows a secret to understand it. How did Simon know that the letter contained encoded information?