Genetic erosion is a process where a limited gene pool of some species diminishes even more. In wild endangered plant and animal species, low genetic diversity leads to a further diminishing gene pool pushing that species towards eventual extinction.

Yet during the last century humanity has lost also a significant amount of agricultural biodiversity despite it being important for food security and dealing with a changing climate.

The textbook example for how things can go wrong when people rely on only one plant cultivar is the Irish Potato Famine. Impoverished farmers relied on a single crop variety, and then one year potato blight destroyed all their crops.

Yet nowadays the humanity rely on fewer plant varieties than ever before. How did we get here? Seed companies prefer to sell large quantities of only few cultivars. Supermarket chains want large quantities of uniform, mass produced goods. For example, they don’t want to sell small amounts of 200 different bean varieties, instead they want a large amount of maybe one or two different kinds of beans.

As for the old landraces (landrace is a domesticated, locally adapted, traditional variety of a species of animal or plant that has developed over time in some region), some are still kept tucked away in some seed bank hidden from consumers and gardeners, many more have disappeared or are on the verge of disappearing. For example, in Latvia we have several agricultural research institutions and botanical gardens that maintain collections of various local plant cultivars, yet many more are in the possession of a single 70+ years old gardener who has grown these plants for decades but will someday stop growing them.

By the way, in Estonia public exchange of non-registered seed varieties is illegal. It is also illegal to sell seeds of local landraces. If a person gives seeds to somebody else, either for free or in exchange of money, then they engage in marketing, and you cannot market non-registered plant varieties. Laws can be fun, no? (Here you can find more info about these laws.)

In Latvia laws are more ambiguous and complicated. Exchanging non-registered cultivar seeds for free isn’t legally prohibited, but laws don’t exactly state that it is allowed either. Selling seeds is legal only if they qualify as “vegetables” under yet another legislative list. I still remember the days from some years ago when in Latvia it was illegal to sell all seeds of any non-registered plant variety. “Here is a whole tomato, strictly for human consumption. *Wink, wink.* By the way, this is totally unrelated, but if you have any questions about how to get seeds out of a tomato or how to grow tomatoes from seeds, feel free to ask.”

Of course, we do need laws that regulate plant and seed sales. We don’t want pests and plant diseases spreading thanks to incorrectly propagated seeds. Nor do we want sellers misleading their customers about what they are selling. But we don’t want laws that make it impossible to maintain plant diversity either.

What does all this mean for the average consumer? Well, it depends.

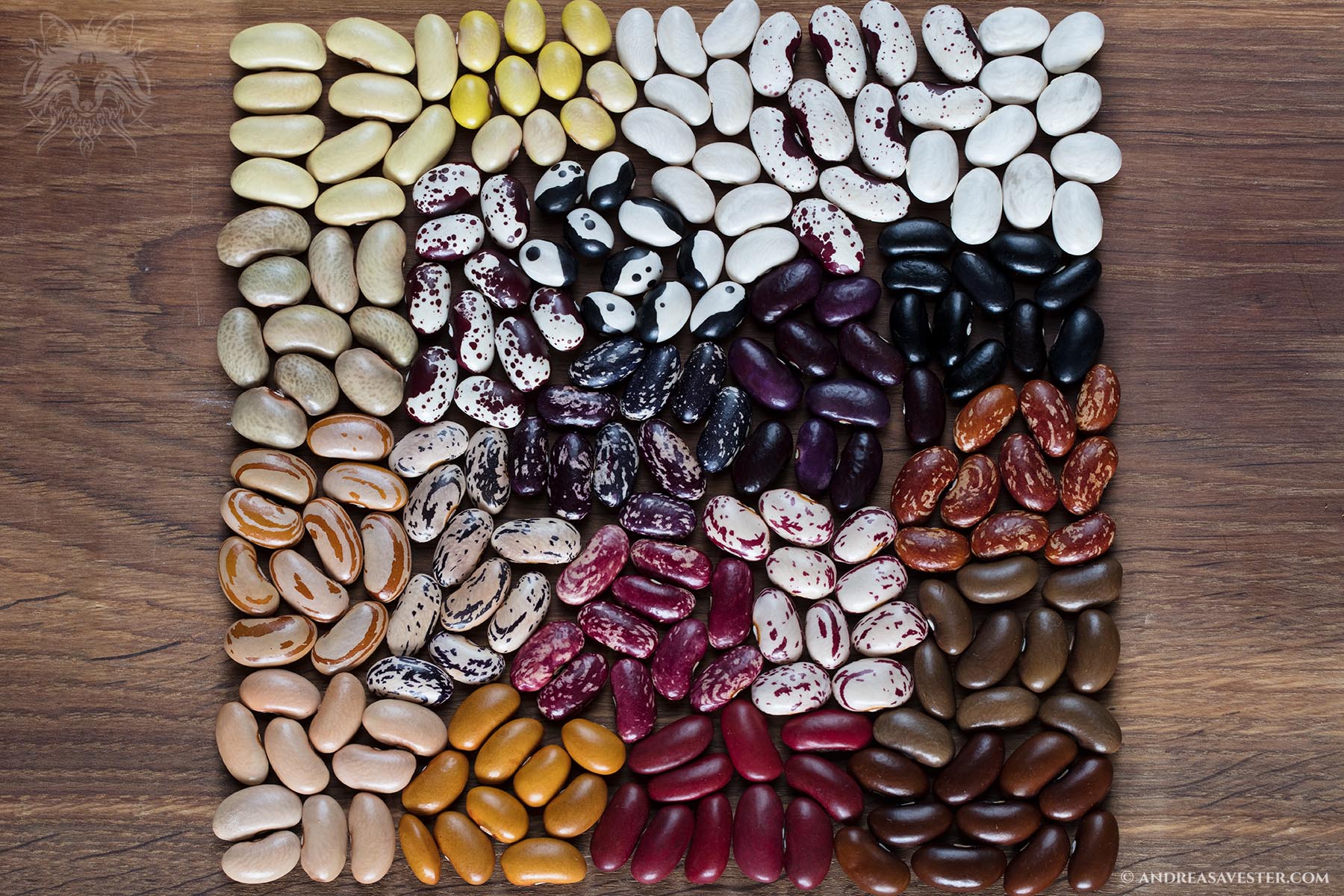

In farmers’ markets, goods are seasonal. For example, even though dry beans can be stored for years, in practice most farmers offer them for sale only for a short period of time after the harvest. This means that for me autumn is the time when I have to buy enough dry beans to last me until the next summer. Well, technically there are always dry beans in supermarkets, but those are no fun. All they have for sale year round is maybe one or two varieties of the most common mass produced beans. Just like children like their candies to come in different colors, I also like some colorful variety is my beans. Therefore in autumn I go to farmers’ markets for bean hunting.

That, and I also prefer to financially support farmers who grow local landraces rather than corporations that sell mass-produced food.

English terms for different beans are, to put it mildly, confusing. Here is an attempt to explain them.

In Latvian, beans that are eaten in their young, green pod stage are called “sviesta pupas” meaning “butter beans.” Here we mostly eat the pods of selected Phaseolus vulgaris cultivars (“French beans,” “green beans,” etc. names in English); regardless of whether the pods are green, yellow, or purple, we call them all “sviesta pupas.” And yes, as the name implies, we often cook them in butter.

Next, there are fava beans (Vicia faba), called “cūku pupas,” which means “pig beans” in Latvian. Those are usually cooked while still inside their pods, but after cooking we throw out the pods and eat only the seeds. Sometimes people also dry these beans and keep them for winter.

Then there are the beans that are cooked after drying. We have “lielās kāršu pupas” (meaning: “large pole beans”), “mazās kāršu pupas” (meaning: “small pole beans”), and “krūmu pupiņas” (meaning: “bush beans”). All my beans in the following photos belong to this category.

The large beans in the middle are Phaseolus coccineus, called “lielās kāršu pupas” in Latvian and “runner beans” in English. The seeds of the plant can be used fresh or as dried beans. The pods are edible whole while they are young and not yet fibrous. From what I understood from British seed catalogs, in English speaking countries people tend to eat the immature pods. Meanwhile, in Latvia, we eat them shelled and almost exclusively as dried beans. Here, over generations, we have bread these beans to have large and pretty seeds, the pods themselves are stringy and coarse compared to the runner bean cultivars grown in others countries where people eat the immature pods. (At least that’s my guess, I have never eaten British or American runner bean cultivars, so I cannot compare from personal experience.)

The rest of beans in these photos are common beans Phaseolus vulgaris, most of them bush beans, but a few are pole beans. (Bush beans are plants that are usually under 2 ft tall. Pole beans, which are also called vine beans and climbing beans, grow much taller and are usually grown on some kind of trellis.) These beans differ from each other not only with their color, their taste also differs. Some are better suited for soups, others for salad.

In my garden, I mostly grow legumes that are eaten fresh during summer and also some runner beans (the large beans in these photos are mine). The rest are from various sellers in the farmers’ market. Often I can find for sale bags with multicoloured beans, this is how I could get beans in so many different colors.

Peas in the above photo are called “lielie pelēkie zirņi” in Latvian, meaning “large grey peas.” (Yes, I have noticed that they look brown, it’s not me who named them.) They are a Latvian cultivar called “Retrija.” Lentils aren’t grown in Latvia, but I like their short cooking times.

Why is genetic diversity important? Here’s an example. Apple scab is a common disease of plants in the rose family that is caused by the ascomycete fungus Venturia inaequalis. Infection typically leads to fruit deformation and premature leaf and fruit drop. The reduction of fruit quality and yield may result in significant crop losses. It’s possible to limit the spread of apple scab with fungicides, but nowadays the emphasis is on breeding apple cultivars that are resistant or immune to this disease.

The first breeding program to produce apple cultivars resistant to scab was initiated in 1940ties. It has been an ongoing effort ever since then. Here’s how it works. You find some wild apple tree or an old landrace that is immune to scab. You cross it with some apple cultivar that has good quality fruit. Some of the offspring will inherit the gene that grants it immunity to this disease. From there you make further crosses with apple cultivars until you get an apple tree that is both resistant to scab and has good quality fruit.

Unfortunately, at this point you don’t get to rest on your laurels. Like all living beings on this planet, fungi can evolve and overcome an individual source of resistance. You see that apple cultivars that were immune or resistant to scab a decade ago start getting sick with it, and you go back to your breeding efforts.

Nowadays, several different virulent races of Venturia inaequalls have been identified, some of which infect and overcome certain genes for resistance.

Over the years, plant breeders found numerous apple trees with different genes that granted them resistance to scab. Vf, the most frequently used source of resistance in breeding programs against apple scab, quickly became insufficient. That’s how we got to diversifying the basis of apple scab resistance. Modern apple breeding programs include the use of molecular markers, making it possible to combine several different scab-resistance genes in one apple cultivar (that’s called pyramiding).

“Historical” major apple scab-resistance genes were Vf, Va, Vr, Vbj, Vm, and Vb. Nowadays there are more, and the nomenclature has been changed with names like Rvi1, Rvi2, Rvi3, etc. Some of these apple scab resistance genes (and gene combinations) have been identified as more promising for developing cultivars with durable resistance, while others are merely recommended for extended pyramids of >3 resistance genes.

The point is: a plant cultivar or landrace that might seem useless right now due to being inferior to other currently grown cultivars can have some valuable genes that will be extremely valuable to plant breeders someday in the future. Moreover, once the climate changes, people will face new challenges. They will need crops that are resistant to too much or too little water, crops that can withstand excessive heat. A changing climate also means that pests and plant diseases will migrate and affect regions where they used to be unknown a few decades earlier.

Biodiversity is always good, unfortunately keeping biodiversity of not only crops is again a thing where there is a conflict of interests between what is long-term good for humanity (and the planet) and what is short-term profitable for large corporations.

Re: runner beans. We grow them regularly, both white and purple. White and purple can interbreed and this can lead to plants that have funky colored seeds and flowers. The beans grow until they freeze, but when they freeze, the pods no longer mature. So our approach is to leave pods to grow on the plant mostly to mature, but at about the half of August, we start harvesting any newly made pods green before they get too stringy, while the previously started pods keep maturing. If a bent pod snaps in half cleanly, it can be eaten fresh whole. If a parchment-like layer has already developed, the pods are too tough and seeds must be shelled out. But even non-mature seeds, unfit for drying, are good food and unlike other legumes, at this size they are worth shelling and cooking. We have also found out that it is best to let the beans completely dry in the pods. They are smoother and easier to shell.

This kind of harvesting maximizes the amount of beans we get from the circa 20 plants that we plant each year. Those 20 plants deliver about 1-2 kg of beans and 1-2 kg of fresh pods, depending on weather and how bees are busy.

Cool beans!

(Oh come on, somebody had to say it!)

Hmmm beans 🙂

I have some bush beans on my balcony every year.