OK, enough with the spider freakout. I’ve been rolling my eyes so hard for the last few weeks that my ocular muscles are sprained. I’m talking about headlines like this:

Don’t journalists have a few other things they should be concerned about right now? This isn’t one of them. This is a great big nothingburger, unless you’re concerned about invasive species and the fate of their naturalized cousin spider, Trichonephila clavipes, which has been here in the southeast US for over a century, is about the same size as Trichonephila clavata (the Joro spider), and is just as harmless.

Oh, you’re not? Then shut the fuck up.

These are big spiders, but T. clavata is harmless. They’ll eat big bugs, but have no interest in you and can’t even bite through your skin. They’re also about the same size as Argiope, which we have in huge numbers up here in Minnesota, but T. clavata is only slightly more cold resistant than T. clavipes and has the potential to slightly extend their range. I only regret that I probably won’t find any way up here in the North.

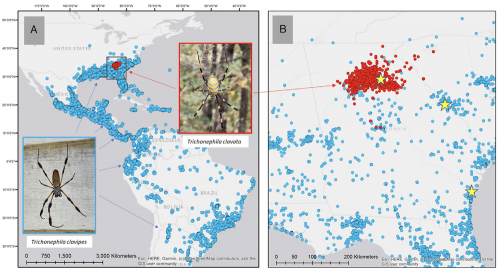

But so what? Here’s where T. clavipes lives now (in blue), and where T. clavata has been found (in red). Don’t panic. They’re big, but they’re beautiful, and they’ll eat lots of grasshoppers and stinkbugs. Welcome them!

Read this for the True Facts.

Ok. We need to talk about the media doing spiders dirty again. Strap in. We’re talking about these GIANT SPIDERS THAT ARE PARACHUTING IN & TAKING OVER THE USA!! *gasp*

Nonsense. Calm down. Here’s what’s up.🧵 pic.twitter.com/t7gVINvOL4

— 🕷scienTEAfic🕷 (@tea_francis) March 9, 2022

Just so you know: last summer, we transplanted several Argiope from the edge of town to our natural garden in our backyard. They did well! I was a little concerned that we wouldn’t have enough food for them — I usually find them in open fields that are swarming with grasshoppers — but the female and male pair were thriving all through August, before they disappeared, as Argiope usually does when the weather cools. We’re hoping they managed to produce an egg sac or two to overwinter, which, with a little luck, will lead to clouds of little baby spiders ballooning over the neighborhood, and a repopulation of our garden. This is nothing to be feared! They’re gorgeous animals.

It’s unlikely that they’ll populate most of the yards in our neighborhood, unfortunately. Lawns are bad. They don’t produce enough big insect biomass to feed these animals.