So why not take advantage of the clarity of vision? Read these articles from 1934.

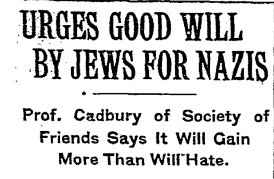

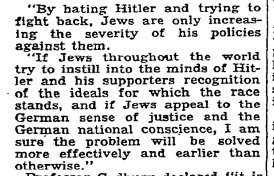

These are from a Quaker quakersplaining to a group of Jews how to deal with that rambunctious fellow, Hitler, who’s being a bit rude out there in Germany. Just be nice!

Read the whole thread. Honestly, we’ve been here before. When will we learn?