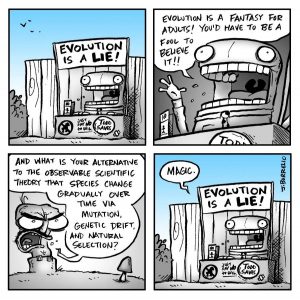

I can’t believe how embarrassed I am for Eric Hovind and John Harris. Eric is, of course, the son of Kent Hovind, which is humiliation enough, and John is the director of Living Waters Europe, so you’d think being shackled to that doofus Ray Comfort would make you reluctant to appear in public, but no, they now appear together in a video that has them capering ludicrously and giggling like maniacs because, oh boy, they’ve got those evolutionists now. They have a knock-’em-dead argument against evolution (it’s always against evolution, because they lack a defensible alternative) that will finally finish off evolution, and it’s so simple they can present it in 5 minutes. Except they don’t. This is a 40 minute video.

Discover “How to Destroy Evolution in 5 Minutes.” Using the lens of mathematics to critically examine the evolutionary timelines from chimp DNA to human DNA renders Evolution, once again, IMPOSSIBLE!

This compelling argument has left evolutionists speechless as they watch their evolutionary science foundation implode.

Join Eric Hovind and John Harris, Director of Living Waters Europe, for an insightful look at one of the most compelling arguments against evolution you will ever hear!

I’m sure they do leave many people speechless. I know I was stunned when I heard it, because it was so appallingly stupid and grossly overhyped. You can skip the first 30 minutes of the video, because it’s just John and Eric patting each other on the back, bragging about how sciencey they are, and rehashing bits of biology 101 (“this is what DNA looks like…”) that are completely irrelevant to their argument, and boasting about how they’ve left people completely convinced that they’ve destroyed science and are now going to church. It’s extremely obnoxious, especially when you get to their actual argument, which is abysmally unimpressive.

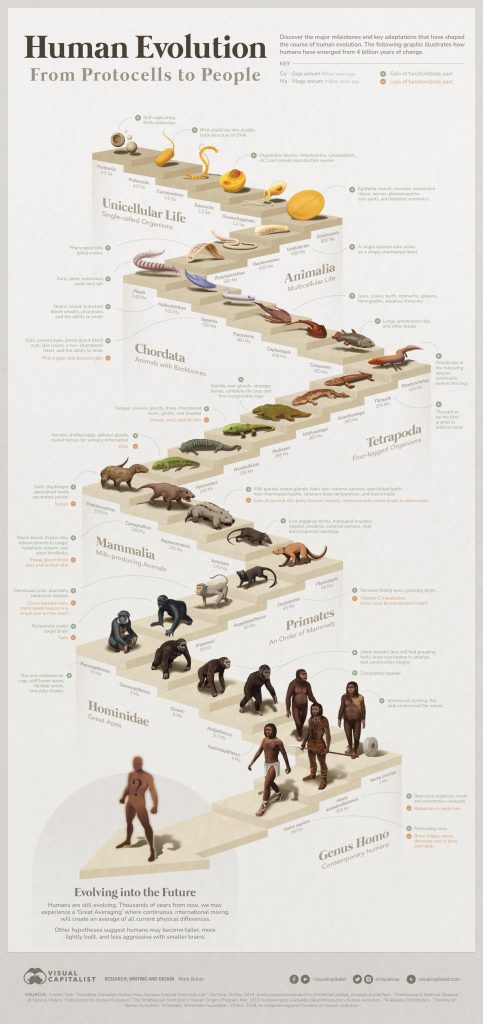

It’s Haldane’s Dilemma. It goes in cycles, where very few years some creationist rediscovers this idea, and goes raving looney claiming that they’ve disproven evolution, and then slowly goes quiet as evolutionary biologists look at them funny and then ignore them. It was first brought up by JBS Haldane in 1957. Haldane was a great scientist, not a creationist, and he brought it up as a potential problem in population genetics that needs to be resolved. It was the problem of substitutional load, that for a mutation to go to fixation involved a cost to the population, since replacement of one allele by another involved the virtual death of members of that population over time. So how could we possibly get enough mutations to transform a chimp-like animal into a person, since surely there are a vast number of genetic changes between the two? Haldane didn’t know how many, but must be lots, right?

Very smart people — much smarter than John & Eric, who know nothing about biology or evolution — wrestled with this problem, but the real question was not whether evolution could occur, but where was the error in Haldane’s assumptions or calculations. As molecular biology proceeded onward, undaunted by a theoretical problem, it was discovered that populations were hugely polymorphic, that is, contained a huge reservoir of widespread variation, that was incompatible with Haldane’s Dilemma. Either the premises for the math was wrong, or plants and animals existed in defiance of the natural laws of the universe.

Evolutionary biologists quickly figured out the flaw. Most of that variation is neutral and can accumulate with little cost. Gosh, empirical reality overcomes the theory, especially the relatively primitive theory of the 1950s. Creationists did not get the memo, though, and every few years they bring up Haldane’s calculations as if they were an evolution-stopper, rather than an early step in figuring out the dynamics of population genetics.

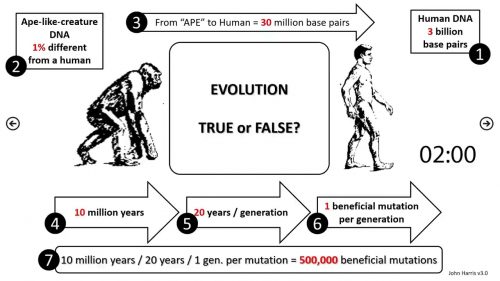

You can skip the whole video, though. It’s only appeal is the spectacle of watching two bozos engaged in a 40-minute pratfall. Here’s their ultimate evolution-killing calculation, presented at about the 30 minute mark.

Note that they are bending over backwards to use numbers that will favor evolution, which is why so much of this calculation is nonsense. Humans and chimps differ by 1% of their genome (it’s more like 3%, but OK), which means there are about 30 million base pairs that differ (they neglect the fact that these are two independently evolving lineages so each needs 15 million changes…let’s forget that, since their numbers throughout are so silly.) That means that in 10 million years at the rate of 1 beneficial mutation (an absurd number) every 20 years, the population can accumulate at most 500,000 beneficial mutations. But we need 30 million! Oh noes!

Every lay person will be baffled by the numbers and will be confused. Every evolutionary biologist will look at it in shock and wonder why this idiot is roaming the streets unsupervised.

You won’t be taken aback. You’ll note that the assumption of 30 million (or 100 million, or whatever) beneficial mutations is false, since most of the differences are neutral or nearly so, so we can just throw away the whole estimate. You might also comment on the fact that their formula is very linear, assuming that evolution is a long march forward, steadily adding beneficial mutations progressively to produce us humans, rather than a process of constantly branching diversification. You’ll also acknowledge that sexual recombination allows genes to evolve in parallel and be reshuffled into novel arrangements. Their little demo disproves creationist evolution, which is an entirely different process than biological evolution.

There’s little point in engaging with anyone presenting this level of ignorance and misinformation. Just pat them on the head, give them a lollipop, and encourage them to stay in school.