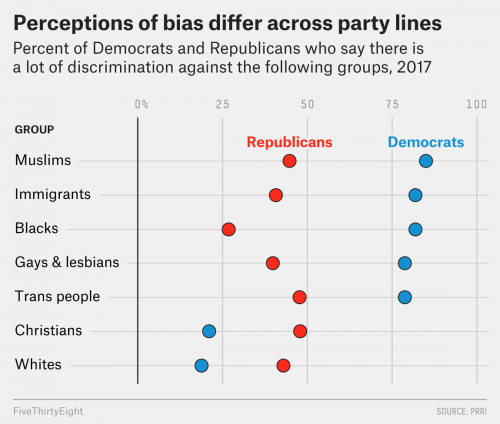

In my view of reality in America, Muslims, immigrants, blacks, gays & lesbians, and trans people are discriminated against. In the minds of Republicans, there is relatively little discrimination against those people, and the real problem is the oppression of…white people and Christians?

Republicans are sick.