Lately, I’ve been curious about this one species of spiders I’ve been breeding, Steatoda borealis. What makes them stand out compared to the other two species in the lab is the size of their palps — they’re significantly larger in S. borealis. It’s got me wondering why they have these massive spiky hooked medieval maces on their faces, where other species have prominent, distinctive bulbs but nothing of the magnitude of this one set of males.

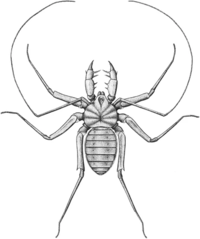

Then I see this species of harvestmen that put my spiders to shame. Look at this gigantic apparatus on the animal’s head! It can be up to 50% of their body weight!

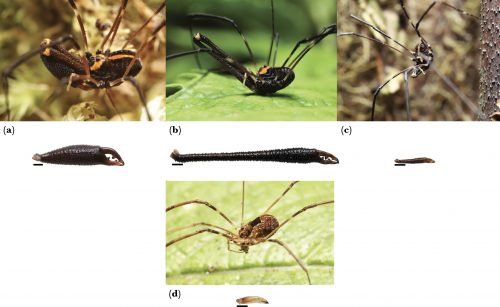

The surprised don’t end there. These harvestmen have three distinct kinds of males, alpha, beta, and gamma, all distinguishable by the morphology of their genitals, and then there are females, of course (only one flavor, though). So four sexes?

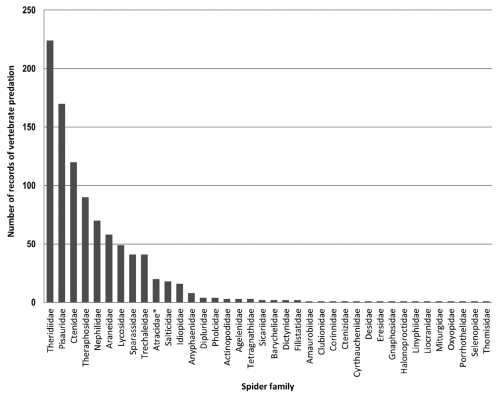

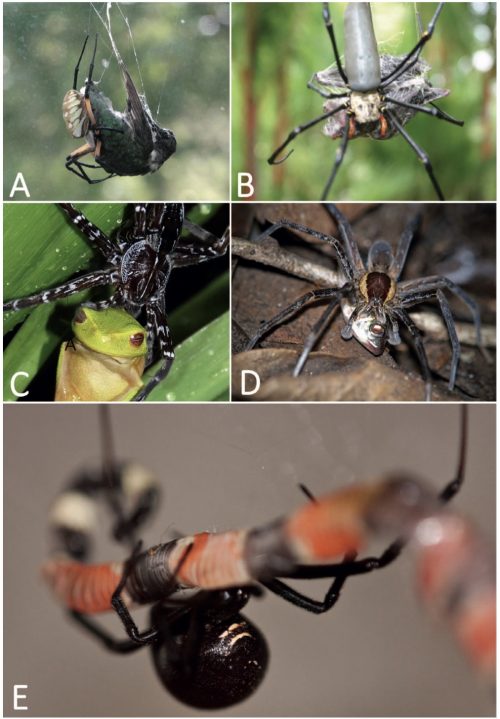

Intraspecific variation in the New Zealand harvestman Forsteropsalis pureora: (a) alpha male (major), (b) beta male (major) (c) gamma male (minor), and (d) female. The second cheliceral segment representative of alphas, betas, gammas, and females is shown underneath the corresponding in situ photograph. Scale bars indicate 1 mm.

So how did this state of affairs come about? Fighting. The males engage in combat to gain access to females. This is a familiar strategy — you’ve got the big bruisers who go straight into battle with their rivals, and while they’re thus engaged, you’ve got the gracile sneaker males who dart in and have sex. Those big genitals are costly and tactics that don’t require that kind of investment are advantageous. We’ve seen similar phenomena in beetles and squid.

Alpha and beta males can have a body mass up to seven times higher than that of gamma males, demonstrating the drastic intraspecific variation found in this species. Gamma males adopt a scrambling strategy, searching through their environment to find mates and avoiding contests with other males, while alpha and beta males use their exaggerated chelicerae as weapons in contests to access females.

Awesome. Now I’m thinking that maybe S. borealis exhibits a pattern of combat that has driven the evolution of more exaggerated genitals. It’s not the only possibility, though — the females of this species are also fairly large and powerfully built. So who’s fighting whom?

I may have an excuse to set up some cage matches in the lab.