Another sad discovery in the lab: another spider, Gilly, has died suspiciously of an exploded abdomen. This has only been happening since I started feeding them waxworms and mealworms, so I suspect gluttony might be the culprit.

Strangely, this has only been happening to my Parasteatoda, while the two species of Steatoda are doing just fine. My colony is currently dominated by Steatoda triangulosa, which is unexpected, since they were relatively rare in our collection sites. I do have about 20 or so juvenile Parasteatoda growing up in smaller containers, though, so the pendulum may swing back in a few weeks when they get promoted to the big breeding cages.

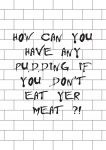

Meanwhile, here’s the latest juvenile (Steatoda triangulosa, of course) that is ready for breeding, I think. The picture catches her at a good angle so you can see both the zig-zag brown stripe down the side of her abdomen, and the sawtooth or triangle pattern you can see dorsally.

You can sort of see a white-flocked Christmas tree on her abdomen, maybe. (NO, IT’S TOO SOON FOR CHRISTMAS REFERENCES!).