This is a nice micrograph of an ascidian egg. A very large egg.

That is definitely the sperm entry point there in the lower half, so it’s apparently a freshly fertilized zygote at this point.

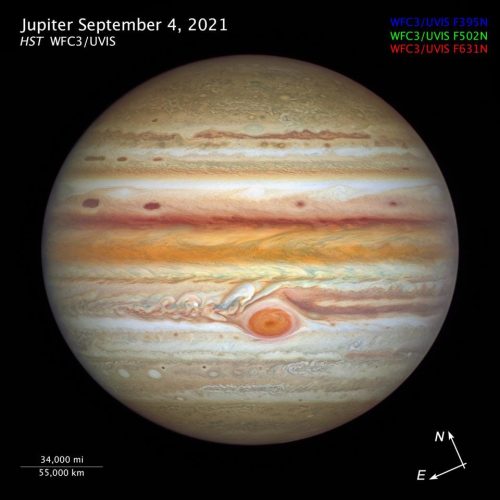

Wait, no, that’s not an egg! It’s Jupiter! I wonder when it will start to gastrulate? I don’t want to be around when it reaches the tadpole larva stage and starts swimming away.

There’s a whole series of Hubble images of the outer planets. Uranus and Neptune are rather blurry, but a very pretty robin’s egg blue, which means obviously that when they hatch they’re going to start screeching to be fed, which will be a bit terrifying, especially when their mama flies back to the solar system.

Several vials labeled “smallpox” have been found at a vaccine research facility in Pennsylvania, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday.

Several vials labeled “smallpox” have been found at a vaccine research facility in Pennsylvania, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday.