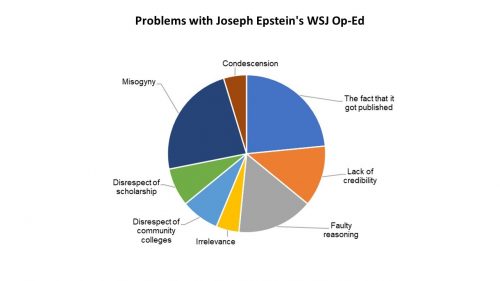

In case you hadn’t heard already, the WSJ published an appalling bit of nonsense from a Joseph Epstein in which, for some unexplained reason, he decided the important issue of the day is to berate Jill Biden for using the title “Dr.” I know. It’s idiotic. She earned the title, use it. There’s a serious reek of sour grapes here, since Epstein has, at best, a BA. Nothing wrong with that, all of my students graduate with a BA, and I’m proud of them. If you want to see it dissected, with excerpts, here’s the summary for you, complete with summary diagram.

But here’s the deal: among themselves, academics tend not to use fancy titles for each other. We might use them when introducing a colleague to others (but see below), but many of us won’t expect it even with our students, or anyone else for that matter. That goes for all you readers, too — I’d rather you didn’t address me as Dr Myers. That feels weird.

One exception, though: if you try to tell me that you’re not going to call me Dr because I only have a mere biology Ph.D., then for you, I’m going to have to insist on the formality.

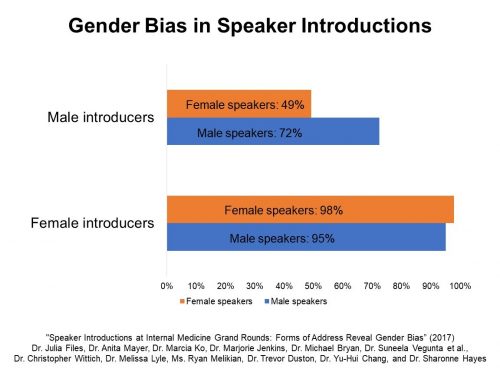

Also, these data bring me up short. There’s a tendency for male academics to be more informal with female academics than with their fellow men.

Wow. When women introduce women, they’ll nearly 100% of the time use their title; when men introduce women, it’s down to less than half the time. That’s simple misogyny, diminishing the accomplishments of women, which Epstein has to an extreme degree, but a surprising number of us men also share. I think I tend to get formal when doing formal introductions, so I don’t think I’m guilty of that, but I’ll be more conscious of the problem in the future. I wouldn’t want to Joey Epstein myself, you know. No one wants that.