If you have a subscription to Netflix, you might want to watch Unknown: Cave of Bones, about the discovery of Homo naledi in the Rising Star cave system. It’s spectacular.

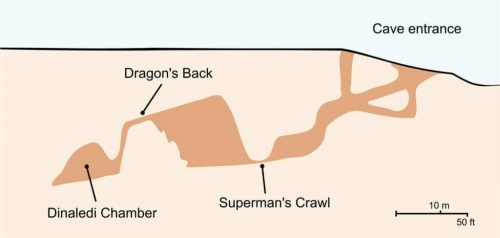

On the other hand, if you’re claustrophobic, you might want to skip it. I’m not particularly, but I watched the video of those women wriggling their way down a narrow crack to reach the Dinaledi Chamber gave me a rising sense of panic. There’s no way I could put myself in that position without having a screaming heebie-jeebie fit.

If you can get past that, though, it’s worth it to watch the adventure of science.