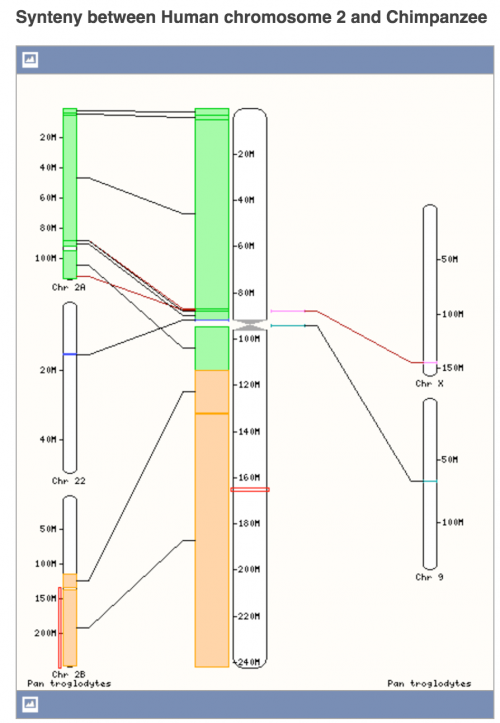

Later today, I’m going to chat with some folks about the creationist claim that human chromosome 2 is not the product of a fusion of chromosomes 2A and 2B in a primate ancestor. I’ve mentioned this guy before, Jeffrey Tomkins, and I’ve criticized the silliness of his approach, which involves staring fixedly at the putative fusion site and ignoring everything else and pompously declaring that he doesn’t see what he expects to see. My response is always “LOOK AT THE SYNTENY OF THE WHOLE CHROMOSOME, YOU ADDLED DOOFUS!”

Synteny is the conservation of blocks of order within two sets of chromosomes that are being compared with each other. That is, stop looking at one tiny little spot and look at the whole chromosome, and ask if there are similar genes in a similar order between human chromosome 2 and chimpanzee chromosomes 2A and 2B. That’s the evidence.

And then I realized that most people don’t know how to look at the genomic data and do these kinds of comparisons. So in this post I’m going to tell you how to do that. It’s fun! It’s easy! It’s like a little game!

First step: go to ensembl.org. Here’s what you’ll see:

We’re going to select “human”. GRCh38.p7 is just the latest, most up-to-date, complete assembly. You can come back later if you want to play with all that data from other species.

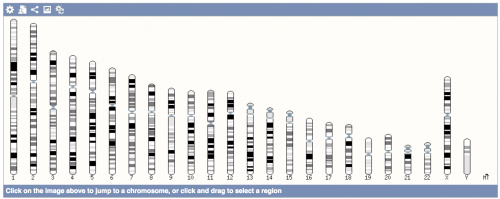

Oh, look. You could suck in the whole human genome sequence to your computer, but then you’d be wondering how to read it and what you can do with it, and might turn into a bioinformatician. Play it safe and easy for now and click on “view karyotype”.

There you are, all 23 human chromosomes and the mitochondrial genome! For now, just click on chromosome 2. From the popup menu, choose “view summary”.

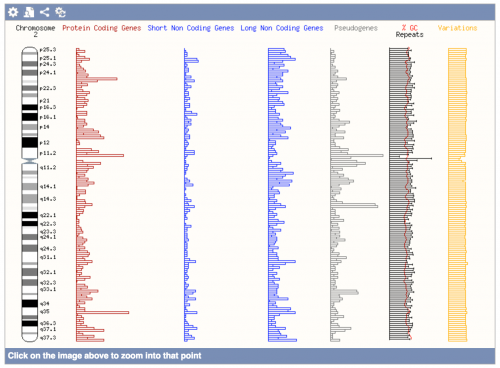

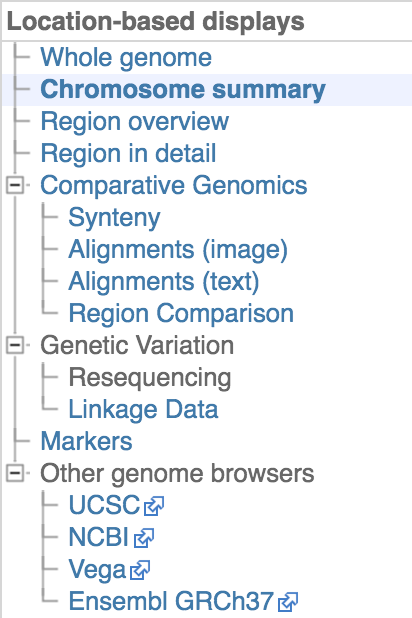

That’s a tempting summary map of what is on chromosome 2, but ignore it for now. Look at top left menu.

Select “Synteny” from the “Comparative Genomics” section.

It’s going to default to showing you how regions with similar sequences line up with human chromosome 2. That’s interesting — you can see that human chromosome 2 is made up of chunks of DNA from mouse chromosomes 12, 17, 6, 1, 19, 16, 5, 11, 2, 10, and 18, but use “Change Species” to switch to “Chimpanzee”. It’s simpler, because we are more closely related to chimps than to mice. Shocking, I know.

Are we done now?

Now if you’d like, you can play with looking at other chromosomes. Or if you’re really clever, you’ll just browse the zebrafish genome.