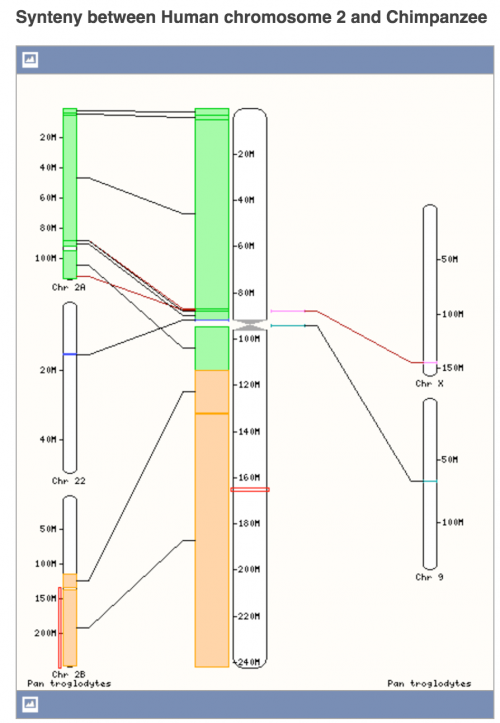

I joined the Great Debate Community last night to talk about this chromosome 2 fusion thing again. One of the topics was about why we have to keep hammering away at the obvious beyond the point where any rational human being would have to accept the facts. Another question was why Jeffrey Tomkins is so committed to promoting a counterfactual that is neither supported by the evidence nor is required by the doctrines of his religion.

If you have an explanation, tell me. Or just watch the video.