I’m not a fan of phys.org — they summarize interesting articles, but it’s too often clear that their writers don’t have a particularly deep understanding of biology. I wonder sometimes if they’re just as bad with physics articles, and I just don’t notice because I’m not a physicist.

Anyway, here’s a summary that raised my hackles.

Chromosphaera perkinsii is a single-celled species discovered in 2017 in marine sediments around Hawaii. The first signs of its presence on Earth have been dated at over a billion years, well before the appearance of the first animals.

A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has observed that this species forms multicellular structures that bear striking similarities to animal embryos. These observations suggest that the genetic programs responsible for embryonic development were already present before the emergence of animal life, or that C. perkinsii evolved independently to develop similar processes. In other words, nature would therefore have possessed the genetic tools to “create eggs” long before it “invented chickens.”

First two words annoyed me: Chromosphaera perkinsii ought to be italicized. Are they incapable of basic typographical formatting? But that’s a minor issue. More annoying is the naive claim that a specific species discovered in 2017 has been around for a billion years. Nope. They later mention that it might have “evolved independently to develop similar processes”, which seems more likely to me, given that they don’t provide any evidence that the pattern of cell division is primitive. It’s still an interesting study, though, you’re just far better off reading the original source than the dumbed down version on phys.org.

All animals develop from a single-celled zygote into a complex multicellular organism through a series of precisely orchestrated processes. Despite the remarkable conservation of early embryogenesis across animals, the evolutionary origins of how and when this process first emerged remain elusive. Here, by combining time-resolved imaging and transcriptomic profiling, we show that single cells of the ichthyosporean Chromosphaera perkinsii—a close relative that diverged from animals about 1 billion years ago—undergo symmetry breaking and develop through cleavage divisions to produce a prolonged multicellular colony with distinct co-existing cell types. Our findings about the autonomous and palintomic developmental program of C. perkinsii hint that such multicellular development either is much older than previously thought or evolved convergently in ichthyosporeans.

Much better. The key points are:

- C. perkinsii is a member of a lineage that diverged from the line that led to animals about a billion years ago. It’s ancient, but it exhibits certain patterns of cell division that resemble those of modern animals.

- Symmetry breaking is a simple but essential precursor to the formation of different cell types. The alternative is equipotential cell division, one that produces two identical cells with equivalent cellular destinies. Making the two daughter cells different from each other other opens the door to greater specialization.

- Palintomic division is another element of that specialization. Many single-celled organisms split in two, and each individual begins independent growth. Palintomic division involves the parent cell undergoing a series of divisions without increasing the total cell volume. They divide to produce a pool of much smaller cells. This is the pattern we see in animal (and plant!) blastulas: big cell dividing multiple times to make a pile of small cells that can differentiate into different tissues.

- Autonomy is also a big deal. They looked at transcriptional activity to see that daughter cells had different patterns of gene activity — some cells adopt an immobile, proliferative state, while others develop flagella and are mobile. This is a step beyond forming a simply colonial organism, is a step on the path to true multicellularity.

Cool. The idea is that this organism suggests that single-celled organisms could have acquired a toolkit to enable the evolution of multicellularity long before their descendants became multicellular.

I have a few reservations. C. perkinsii hasn’t been sitting still — it’s had a billion years to evolve these characteristics. We don’t know if they’re ancestral or not. We don’t get any detailed breakdown of molecular homologies in this paper, so we also don’t know if the mechanisms driving the patterns are shared.

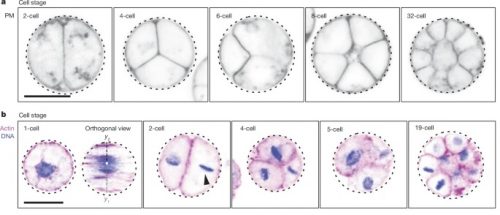

I was also struck by this illustration of the palintomic divisions the organism goes through.

a, Plasma membrane-stained (PM) live colonies at distinct cell stages, highlighting the patterned cleavage divisions, tetrahedral four-cell stage and formation of spatially organized multicellular colonies (Supplementary Video 5). b, Actin- (magenta) and DNA-stained (blue) colonies at distinct cell stages showcasing nuclear cortical positioning, asymmetrical cell division (in volume and in time) and the formation of a multicellular colony. This result has been reproduced at least three independent times.

Hang on there : that’s familiar. D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson wrote about the passive formation of cell-like cleavage patterns in simple substrates, like oil drops and soap bubbles, in his book On Growth and Form, over a century ago. You might notice that these non-biological things create patterns just like C. perkinsii.

Aggregations of four soap-bubbles, to shew various arrangements of the intermediate partition and polar furrows.

An “artificial tissue,” formed by coloured drops of sodium chloride solution diffusing in a less dense solution of the same salt.

That does not undermine the paper’s point, though. Multicellularity evolved from natural processes that long preceded the appearance of animals. No miracles required!