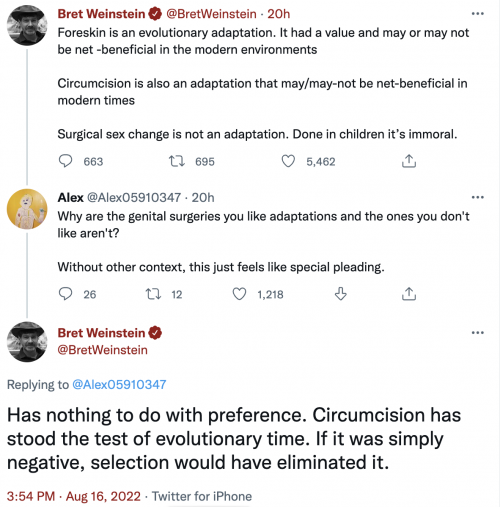

It was a big win for Evergreen College to get rid of him, because he had to have been teaching it badly. This is the kind of obsolete adaptationist garbage he was teaching, and the kind of twisty reasoning he uses.

Let us begin the vivisection.

Foreskin is an evolutionary adaptation.

No, he does not know that. There is no evidence to suggest that it has any significant effect at all, in an evolutionary sense. There is no history of people born without foreskins in any kind of competitive interaction with people with them; there is no evidence of a differential reproductive advantage in any human lineages.

He’s making shit up. This is indicative of a crude adaptationist mindset where everything must have an adaptive effect.

It had a value and may or may not be net -beneficial in the modern environments

What value? Be specific. What change in value in modern environments has occurred?

Circumcision is also an adaptation that may/may-not be net-beneficial in modern times

Loss of a foreskin is not an adaptation — it’s not heritable. It’s a cultural trait. It’s effects are complex: sure, it may be important in establishing a group identity (a cultural phenomenon again!), but it probably has also led to some small number of babies bleeding out. So what if it may or may not be beneficial? It’s a thing. People also get ear piercings, or tattoos, or funny haircuts. Are those adaptations now?

All this adds up to Weinstein’s kicker.

Surgical sex change is not an adaptation. Done in children it’s immoral.

Alex up there hits the nail on the head. Why is one kind of modification (circumcision) adaptive, but another kind (gender affirmation) “immoral”? This is all just bad rationalization by Weinstein. I wonder if he has a sense of shame left any more?

Nope.

Has nothing to do with preference. Circumcision has stood the test of evolutionary time. If it was simply negative, selection would have eliminated it.

There you have it: if it exists for some length of time, it is good and must have some advantage, or evolution would have eliminated it, because every bad thing is culled by the all-seeing perfect eye of natural selection. Migraines, bad knees, PCOS, religion, hernias, primogeniture, aging, the infield fly rule in baseball, wisdom teeth, vitamin C dependency, and war, all blessed by the flawless filter of evolution, or they wouldn’t exist anymore.

Good god, what a panadaptationist idiot. They really do exist. With bad logic and science like that, you know all he’s doing is signaling fallaciously to his bigoted anti-trans cronies.

But also, I have to wonder: why does he consider evolutionary consequences to be the only thing we consider when doing a thing? I blog because I enjoy it, not because it gives my offspring some advantage. You can like a rainbow or dancing or music or being in the company of friends because it makes you feel good — not everything is derived from some kind of biological calculus.