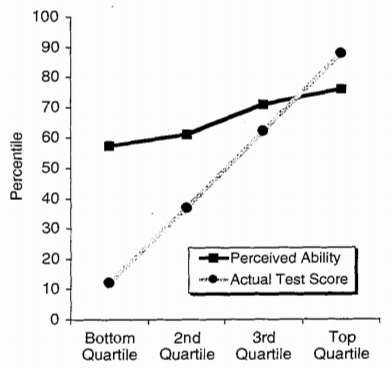

The Dunning-Kruger Effect states that people with the lowest competence tend to overrate their competence, but people with the highest competence tend to underrate themselves. This was shown in 1999 paper by Dunning and Kruger.1 Here’s one of the figures from the paper:

This figure shows results from a test on humor. People are scored based on how well their answers agree with those of professional comedians, and then they are asked to assess their own performance. There were similar results for tests on grammar and logic.

The Dunning-Kruger effect has entered popular wisdom, and is frequently brought up whenever people feel like they’re dealing with someone too stupid to know how stupid they are. But does the research actually mean what people think it means?

Before reading into this subject, I must admit that I had a major misconception. I thought that people’s self-assessment was actually anti-correlated with their competence. I thought someone who knew nothing would actually be more confident than someone who knew a lot. (This leads to an amusing dilemma: Should I choose to give myself a lower rating, because it would that increase posterior probability that I’m more competent?2)

But it is not true. People who know nothing are less confident than people who know a lot. People who know nothing are overconfident relative to their actual ability, but they are still not as confident as people who have high ability.