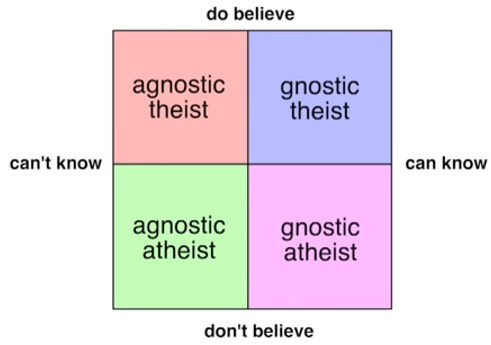

Rebecca Watson, unfortunately, reminded me of a meme from the old days of new atheism. It’s those agnostic atheism diagrams.

Credit: Skepchick

I have a rant in me about these diagrams. Agnosticism and atheism are political terms, and whether you identify with them has more to do with what you find useful in your social context than the literal definitions of these terms. This diagram became popular because it explains and justifies a particular choice in identification labels, but it is not an appropriate framework to understand more broadly why people do or do not identify as agnostic. Thus, as a meme, this diagram is a barrier to empathy and understanding of fellow nontheistic folks of diverse label preferences. Also it’s just kind of incoherent.

Why agnostic atheism?

Before I criticize the meme, it’s important to first understand what the meme was intended to do, and why it was effective.

When I started identifying as atheist around 2006, I pored over a variety of introductory articles on atheism. These articles were greatly preoccupied with explaining the definition of atheism and adjacent terminology. I too in my early blogging years was very preoccupied with this subject. And one of the biggest things that needed to be explained, was why you don’t need to be absolutely certain there is no god in order to be an atheist.

Today it’s taken for granted that atheism does not require certainty about god, but that’s precisely because decades atheist advocacy have been so effective at persuading people of this fact. And it’s not really a matter of “fact”, is it? To some extent the definition is whatever we say it is. When religious folks assert that atheism requires certainty that there is no god, it may be a self-serving way to give atheists as little space to exist as possible, but it’s still a correct description of what “atheism” means to them. It’s not a correct description of what atheism means to atheists though.

Not all nonreligious folks agreed on the definition of atheism. Some people agreed with the assumption that atheism required certainty about gods, and therefore identified as agnostic, not atheist. And in fairness to those folks, there were a lot of different competing labels early on, and the people who advocated the “agnostic” label weren’t obviously any less reasonable than those who advocated “bright”. Nonetheless, for those seeking to politically mobilize as a nonreligious coalition, “atheism” had become the most powerful rallying cry. Within the atheist movement, agnosticism was a flame bait topic, as people would regularly accuse agnostics of being overly meek fence-sitters.

There were a variety of ways to explain how atheists didn’t need to be absolutely certain. In introductory articles, it was common to make distinctions between positive and negative atheism, implicit and explicit atheism, weak atheism and strong atheism. Even in 2007, I had the impression that these distinctions were overly loaded and somewhat archaic, but I guess you can still find articles about it today. Another approach was Dawkins’ 7-point scale, where a 1 is a theist who knows there is a god, and a 7 is an atheist who knows there isn’t a god. Dawkins said he was a 6, and most atheists would be in that vicinity.

But I think the most effective explanation came from the simple observation that atheism and agnosticism are not, as conventionally assumed, mutually exclusive. This is easy to see because there is a clear distinction between believing there is no god, and knowing there is no god. Furthermore, it is easy to graphically illustrate with a 2D diagram. The diagram conveys the idea that atheism and agnosticism are two orthogonal concepts, and that you can be one, the other, both, or neither. It also suggests a spectrum, which is important if you want to provide space for a bunch of misfit individualists who can’t agree on definitions. As long as you don’t think about it too hard.

Let’s think too hard about this graph

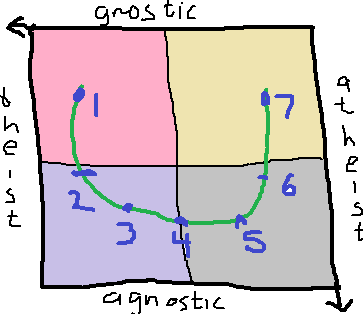

The “classical” way of understanding agnosticism, is as a state that’s between theism and atheism. Dawkins’ 7-point scale serves as a good example of this framework. 1 is “strong” theism, 7 is “strong” atheism, and 4 is agnosticism. Agnostic atheism might describe the range of around 5-6. Dawkins’ scale could, hypothetically, be embedded into the 2d diagram like so:

I have learned to deliberately draw diagrams poorly in order to protect against people who might take the images out of context as if they were serious.

But the 2D diagram obviously allows for so many possibilities not included in Dawkins’ scale. For example, there’s this whole upper region of the graph not covered by the scale. I could be in between atheism and theism, while being completely gnostic. But we have to ask ourselves, does this make any sense? Not only is it hard to believe that anyone would hold this position, it’s hard to believe that we would recognize it as gnosticism. If I told you that I think we can know whether there is a god, but I don’t believe one way or another, would you exclaim, “Wow, I used to think you were agnostic until now!”

The incoherence of gnostic (un?)theism puts to lie the idea that the 2D diagram is offering a superior framework to a simpler 1D scale. If we’re being honest, the diagram isn’t a 2D spectrum at all, it’s just a diagram of four distinct categories. It might as well be a Venn diagram.

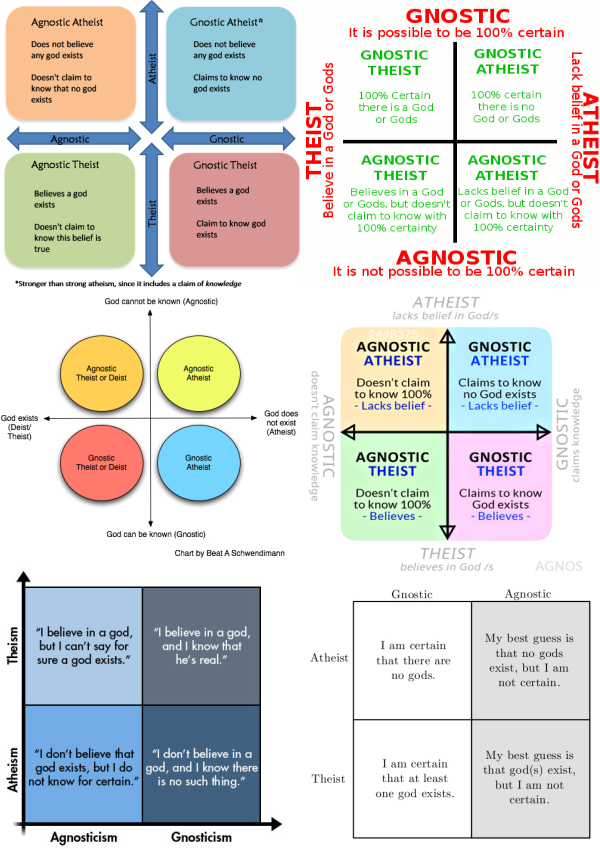

Now let’s look at more examples of the diagram.

In this crowd, you can see why I feel the need to draw my diagrams really poorly. Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

In these diagrams, agnosticism is defined as:

- “Doesn’t claim to know that (no) god exists”

- “It is not possible to be 100% certain”

- “God cannot be known”

- “Doesn’t claim knowledge”

- “can’t say for sure a god exists”/”I do not know for certain”

- “I am certain that there are no gods / at least one god exists”

Well we got 6 random diagrams from a google search, and at least 4 distinct definitions between them. Knowledge is not necessarily the same as certainty, which is probably also different from “saying for sure”. And there’s a difference between claims about your own knowledge/certainty, and claims about whether it is possible to know or be certain.

These definitions raise many questions. What does it mean to be between agnosticism and gnosticism? Is it a scale from 0 to 100% certainty? Is it a claim that it’s possible to be 50% certain? Is it a claim that it’s 50% possible to be 100% certain? Is it a claim that you only sorta know whether god exists or not?

And then there’s the question of what it means to be between atheism and theism, if it is orthogonal to certainty and knowledge. Does that mean that you don’t believe either way? How can you be certain or uncertain about a belief you don’t even have? Maybe it’s a belief that only there is only half a god? Or that there’s a 50% chance of God? How is that distinct from 50% certainty?

And some of these may be legitimately interesting questions with real answers to them, but it sure doesn’t seem like that’s the goal of the graph. The goal is, as I said, to establish four distinct categories, and just sort of hint at a spectrum without having to actually address any of the questions that raises. I have to conclude that the only reason this graph is effective is because most people are completely incurious about graphs.

Disrupting assumptions

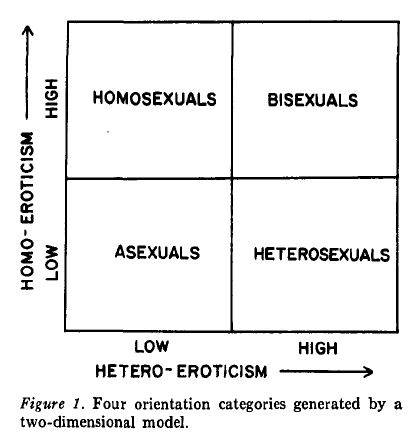

As it happens, I’m somewhat of a world expert on terrible graphs of orientation. The agnostic atheism graph strongly reminds me of another terrible graph proposed by psychologist Michael Storms in 1979:

Yes, we have vintage terrible graphs from old scientific papers.

Well, it’s not that terrible, it’s just mediocre. But if you look at the other terrible graphs in my article, you might find that there are many ways to disrupt its assumptions.

The first way, that seems to come most easily to most people, is to add more axes. For example, earlier I pointed out that there were at least 4 distinct definitions of agnosticism, so why not depict those as four distinct axes? (It’s obvious why not, but humor me.) Alternatively, we could add many other identity labels to the graph, such as freethinker, skeptic, humanist, secularist, and bright.

What’s that you say? Bright is sort of a loaded term? Just because you don’t believe in the supernatural doesn’t mean you’re a “bright”? What’s next, will we make an axis that tells you whether or not you’re “godless” based on whether you are without gods? I totally agree, “bright” and “godless” are too politically loaded. Putting it on the graph would be quite a Choice.

But! Agnosticism and atheism are also too politically loaded! I’m not exaggerating, I really mean it. I, who just wrote a short history slash rant about the politics of agnostic atheism, all off the top of my head–yes, I, the very same person–happen to think that agnosticism and atheism are politically loaded terms.

And what if Alice presents a 2D graph, and Bob decides that it really ought to be a 8D radar chart full of things that Alice wasn’t even thinking about? Where does Alice fit along the 6 additional dimensions? What if Alice asserts that in fact she still prefers it with only 2 dimensions? You too can experience what Alice is feeling by trying to fit yourself into the tertiary sexual attraction spectrum. As the saying goes, you can lead a horse to an identity chart, but you can’t make the horse identify with it.

The agnostic atheism chart has a lot of makings of a chart that not everybody is going to agree with. There’s the highly dubious horizontal and vertical “spectrums”. Politically loaded terms treated as neutral ones. At least four different definitions of agnosticism treated as interchangeable when they’re clearly not. And the chart follows the naive understanding that “agnostic” and “atheist” are simply things that you are, rather than words you identify with, as demanded by circumstance. In order to determine where you fit in, the question isn’t “Where are you on this chart?” but “What’s your opinion of this chart?”

Let’s find out!

Personally, I live in a post-atheist world. I used to be involved in atheist activism, but I quit as the movement became increasingly toxic. Richard Dawkins, to whom I give credit for doing his part to destigmatize atheism, is now doing his part to reinforce stigma against trans people, and I won’t have it. In the mean time, my personal social sphere is increasingly filled with silently non-religious people (or maybe religious? who knows), and it’s kind of a non-issue. I identify as an atheist, but drilling down into adjacent labels just feels like unearthing old political arguments that most people don’t care about.

That’s just one personal narrative, and I admit, a highly unusual one. What other personal narratives are out there? My suggestion is that instead of using graphs to try to fit everyone into a single framework, we adopt a “let’s find out!” attitude. Let’s find out why people identify the way they do. Why do people identify as atheist and/or agnostic? Where do they see themselves in relation to other identities? What’s up with the “nothing in particular” group that according to surveys, is larger than agnostics and atheists combined? Aren’t you curious?

And if the answer sometimes involves terrible graphs, so be it. I love terrible graphs.

There’s another distinction to be made here: between knowing there is no god, and knowing that all the claims you’ve heard from others about god(s) are unfounded or false. It’s possible to suspect that there COULD be some sort of all-powerful, all-knowing entity out there that humans might call “god” if we met him/her/it/them, while dismissing, with 100% certainty, all human claims and stories about the gods we’ve believed in so far.

When theists say things like “you can’t prove the nonexistence of god” or “you can never really know there is no god,” we can still reply “That’s true, but we still know you’re full of shit.”

I identify as an atheist, but drilling down into adjacent labels just feels like unearthing old political arguments that most people don’t care about.

The question is, are those old political arguments still relevant to you or to your life experience? If not, then no, you don’t have to bother with those pesky extra dimensions.

Siggi has made some true and useful points here, but I will add one more.

The whole discussion hinges on ideas such as “What is the meaning of the word: atheism”? or whatever word we are focusing on.

The new problem is that some people feel that the true definition of all words is always how they are mst commonly used. But others feel that exceptions t this must be made for specialist or technical vocabulary. Thus, the majority of people might not admit anything in the above posting, and might just say that, to them, agnostic just means shy atheist.

I feel if we let a non specialist population redefine words with specific distinctions of meaning, then that could have the effect of erasing our whole discussion. So, even though I generally say that usage determines definitions, I feel strongly that we must defend our conversation by keeping our more specific definitions of these terms, and in this case rejecting definitions by common usage. I don’t care if that makes me an elitist. Otherwise, we can’t even say or think these thoughts.

For context, consider another example: many little kids who see a pregnant person may be told that a baby is groin in the parent’s “stomach”. Many little kids see this and “learn” this before they are old enough to learn the distinction between a uterus and a stomach. And I bet many of them never get the corrected information. This, it is possible that the most common word for the place a baby grows is stomach and not uterus.

If we let mere common usage dictate the definitions of words, then would obstetrics students be required to say stomach when they mean uterus? Would medical schools have to explain that half the population has two stomachs, but that one is not part of the digestive system? Clearly, we need to defend the existence of the word uterus.

Likewise, we need to defend the definitions of he words atheist and agnostic, and not let a popular vote conflate them.

Thus, we need to insist that some definitions of atheist and agnostic are unacceptable.

So I support what Siggi said, but I’d add that there are these other issues such as definitions that are also keys to this discussion.

@Bruce #3

I agree, thanks for putting that into words.

A lot of my thinking is influenced by thinking about LGBTQ+ identities. In that context, there is a lot of value placed on self-identity, and there’s a sense in which people of a given identity have more authority on what that identity means. And so when I see Christians defining atheism in a certain way, and atheists defining it in another way, I’m inclined to think the atheist definition is more “correct”, regardless of whether atheists are smaller in number.

The way you put it, comparing it to specialist or technical vocabulary, that’s another more analytical way of understanding the situation.

Then the next question is how this informs our approach to agnosticism. My intuition is that you need to ask people who identify as agnostic what it means to them. And we might need to make a distinction between agnostic atheists, and people who primarily identify as agnostic. Although, in my experience, people who are primarily agnostic are a bit all over the place in terms of what that means to them.

A lot also depends on how you define “god”.

If you define “god := love” I’m not going to disagree with you, love exists… that’s it though…

If you claim god created man, that puts you in the realm of biology and that statement is easily disproven.

If you claim god created the universe, that puts you in the realm of physics, and while we aren’t there *yet* (or perhaps we are, depending on how you define terms) I see no reason why this couldn’t be a disprovable* claim (and I in fact believe it to be so for most common definitions!)

Or in one case in a discussion with a (mathematical) philosopher it all boiled down to the fact that since all effects must have causes, he had to have a “god := first cause” as an axiom of his logic. To which my reply was that “the universe exists” was an equally sufficient axiom, and more believable by our experience. (This discussion also involved large quantities of wine, so please don’t ask me to repeat the argument verbatim…)

In other words, depending on your definitions I might be an atheist, an agnostic, or a believer. I generally call myself an atheist though.

*Also, anyone who says “you can’t prove a negative” or anything like that… we’ve known how to do that for several thousand years now. There is no largest prime number.

I was tempted to say that this strikes me as much ado about “nothing” — but that would be far too dismissive of something so serious (in my old age, how could I not take the subject seriously?). I have come a long, slow way from being raised and being a practicing Catholic to being….where do I fit on these graphs and scales anyway? “Politically” I couldn’t care less. More deeply, realistically, and personally (if definitions could accurately depict a state of mind), I find myself somewhere between deism and agnosticism The only thing I believe with near certainty is that human beings can’t know what they can’t know. But I suppose I could be wrong.

The new problem is that some people feel that the true definition of all words is always how they are [most] commonly used. But others feel that exceptions [to] this must be made for specialist or technical vocabulary.

The meanings of words like “atheist” and “agnostic” are not really a “technical” matter, like biology or psychology; they’re a social, political, emotional and personal-identity matter, and the whole point of having this discussion is about how the broader public (as in, one’s friends, family, bosses, and whoever else hears anything about one’s beliefs and priorities) understand those words when they hear us use them.

I feel if we let a non specialist population redefine words with specific distinctions of meaning, then that could have the effect of erasing our whole discussion.

The problem, as I see it at least, is that some people are trying to manipulate the public’s understanding of the words, in order to undermine our ability to speak honestly and clearly to the public. It’s not a problem of “non-specialists” interfering with the “specialists'” ability to communicate; it’s one of dishonest people trying to spread lies and degrade everyone’s ability to communicate the truth, with the intent of further marginalizing people they hate.

*Also, anyone who says “you can’t prove a negative” or anything like that… we’ve known how to do that for several thousand years now. There is no largest prime number.

My response to that assertion is simply that atheists don’t have to prove any negatives. Atheism isn’t really a positive claim, it’s just the dismissal — for lack of evidence, among other reasons — of all the positive claims made by theists about gods and other supernatural beings and events.

“Agnosticism and atheism are political terms, ”

At that point I stopped reading, If you dont know what atheist or agnosticism mean – you probably shouldnt be commenting on their utility.