How do you design a new course?

First message: don’t. It’s a lot of work, and we professors are already underpaid and overworked. You do not get a bonus for teaching more, you are a salaried worker and you get paid whether you teach one course or five courses. You should be compensated for your labor, but you won’t, and in fact many of the institutions of university governance will conspire to discourage compensation for taking any initiative.

For instance, my university has a precisely defined formula for calculating workload: we plug in the number of lecture hours and lab hours we teach, and it spits out a number of credit hours we’re teaching, which is supposed to be right around 20 (different universities will have different expectations). We all know each other’s number. We strive to keep everyone’s workload equal, because that’s only fair, right? Of course, there are many assumptions built into the formula — the weighting of labs vs. lectures, for instance — and there’s nothing about the difficulty of courses. I could teach nothing but introductory freshman courses with no labs, while someone else could be assigned a set of new, advanced upper level lab electives, and we could have exactly the same number, but you know which of us would be working much harder. We informally try to balance that kind of load, but that magic number is really only a rough guideline.

It’s also a fiction for another reason: we fudge it to keep from breaking the system. For example, we have a whole course and other workload obligations that are not plugged into the formula, because to do so would increase the number, and require us to stop teaching other courses that we require. Or for the administration to hire more faculty to distribute the load, and we know that is not going to happen. We can’t break our obligations to students, and the administration can rely on our sense of responsibility to compel us to do more work with no extra pay.

Which brings me to more terms of art, ones the students know well: required courses vs. electives. We have a set of core courses in the discipline which every student in biology must take in order to graduate, which means we must teach them. If we just declared that we don’t have enough faculty to teach cell biology this year, for instance, it would hurt the students, because it would basically add an extra year to their graduation time. Which would make their parents unhappy. Which would make the administration unhappy. These courses are required in more ways than one.

These required courses also tend to be standardized across all universities. The cell biology course you take at Harvard is going to be very similar to the one we teach at UMM. There are pedagogical variations, of course, but the content is a kind of shared understanding among biologists everywhere. There isn’t a lot of latitude in what you teach in these courses, but there is space for revising how you teach them, which makes them fun. However, you’ll only rarely have the opportunity to design a required course. Most likely, you’ll be assigned one and then the challenge is to teach a known quantity well.

Electives are more complicated. Some also have a fairly standardized body of content — anatomy is an elective in our department, but it really hasn’t changed in a century or more. Others are about more recent innovations, or reflect the instructor’s research interests, or synthesize different areas. These are the courses we live for! Teaching a course is more than just a way to pass on known knowledge to younger people, but also a way for us to learn. The discipline involved in learning how to teach a new course requires us to stretch our brains and master new material.

That leads us to our dilemma. We don’t get monetary rewards for teaching new classes, but there are great intellectual rewards, and it’s good for the students to learn what’s new and exciting in our discipline. So we inflict this extra effort on ourselves.

This is my situation. I identify as a developmental biologist. I was specifically hired as a developmental biologist, with a focus on evolution. But I haven’t taught either of those things in years! Due to the usual inevitable faculty changes, retirements and departures and so forth, I’ve had to take on two major courses that eat up most of my allotted work load: in the fall, every fall, I teach cell biology, a required core course in the major; every spring, I teach genetics, another big lab course, a standard elective, but one that is required for our pre-professional students. We can’t stop teaching either one, and in a very small department we don’t have the slack to swap in an alternate instructor now and then. My developmental biology course is a lab course, and simply adding it to my load would bump me well above our magic workload number, as well as leaving me exhausted and drained and unable to teach well. So I’ve found myself in a rut of cell biology-genetics-cell biology-genetics, etc., etc., etc., with a few low-credit supplemental courses around the edges.

I decided last year to put together a new course in developmental biology with a twist, that I could wedge in the scant space in my workload. But I’ll write about that tomorrow.

P.S. A few hints for you brand new academics applying to enter the professoriate. We don’t get permission to hire new people because we tell the administration we’d like to offer an exciting new elective. We get permission because we tell them we need the support to teach a required course or courses. That means our job ad will say we’re hiring someone to teach Course X, which is a necessary part of the curriculum, and which is typically a common course taught at many universities. If you don’t have teaching experience in that course already, you damn well better do your research and figure out precisely what kinds of things should be on the syllabus for it. We always ask questions to probe whether you understand what the obligations are (and we also like it if you have creative ideas about pedagogical innovations to make it more interesting to teach). We also want to know that you’ve thought about what is appropriate for the students — one big mistake we see all the time is when we ask about how the candidate would teach a second year course and they enthusiastically gave us an outline of a graduate level course in their specialty.

We also typically ask about what kinds of electives they would like to teach. Again, an outline of a graduate level course is not what we want: we’d like to hear about a course you find exciting that would integrate well with our existing courses, and extend them in new directions. That means…do your homework and find out what electives we do teach and propose something that fills a gap in our curriculum and also goes one step beyond what we offer. For instance, we have core courses in ecology and molecular biology — think about what we teach already, and propose something that an undergraduate who completed molecular biology would want to take, or something that would be a natural progression from our ecology course, or something that related the two. And show some passion and enthusiasm, and that you’ve actually thought about what you’d love to teach.

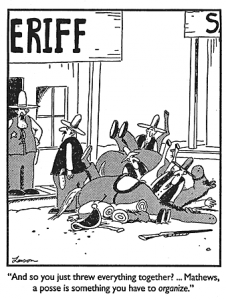

Also, we try not to throw new faculty directly into the challenge of designing a course from scratch in their first semester, so don’t panic.