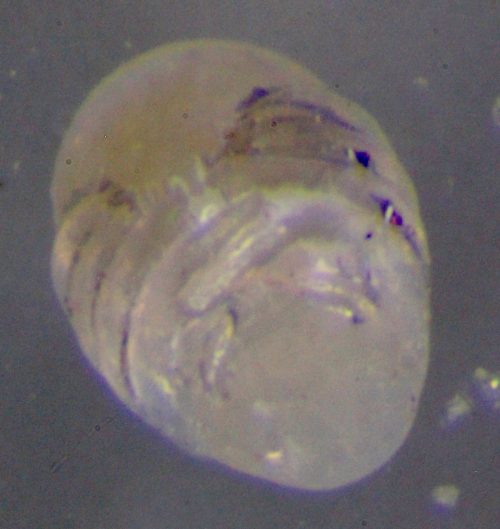

Our new development in spider development is pretty basic stuff. We’re dechorionating embryos! That is, stripping off a thin membrane surrounding the embryo, so we can do staining and fixation and various other things. It’s a standard invertebrate technique — it turns out you can remove it by just washing them in bleach. Look, it works! This is a Parasteatoda embryo.

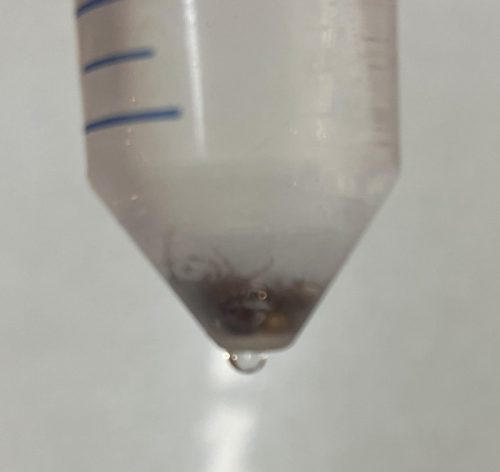

We’re still tinkering with the timing of the treatment. Five minutes is way too long, which basically dissolved the whole embryo. All it takes is a brief wash to break the chorion down. We’re also working out methods for manipulating them — they’re tiny! Just pipetting them into a solution is a great way to lose them. We’re now using a cut off microfuge tube to make a cylinder that we cap with a sheet of fine nylon mesh, to lower them into the solution. Of course, then we have to separate the embryos from the mesh. Fortunately, we opened up one egg sac and 140 embryos rolled out, so we have lots of material to experiment on.

The next question is whether they survive our abuse. We’ve got some of them sitting under a microscope, time-lapsing their response. We’ll see if they grow…or die and fall apart.