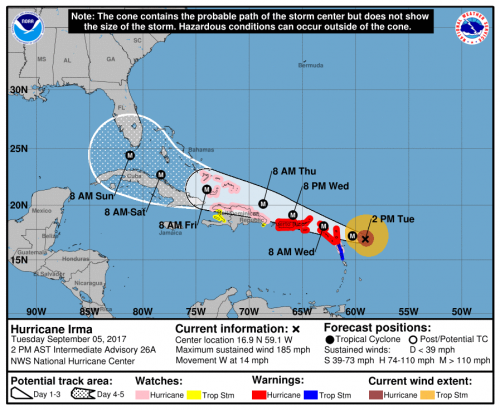

One side of the country is looking at Hurricane Irma rushing at them. I wouldn’t want to be in Florida right now.

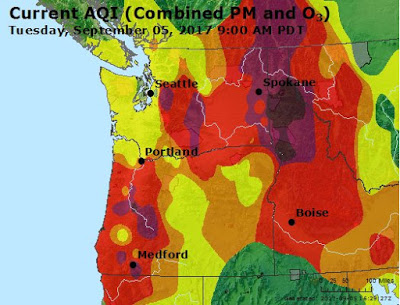

The other side of the country is on fire. I’m hearing stories from family members that it is snowing ash.

If only we could bring the two together for a day!

I’ll just mention that we’ve got clear skies and 20°C temperatures out here in the middle. Minnesota is perfect! Until December, anyway. Maybe November. Depends on your cold tolerance, I guess.