You need to include a scale with these images, Riley Black!

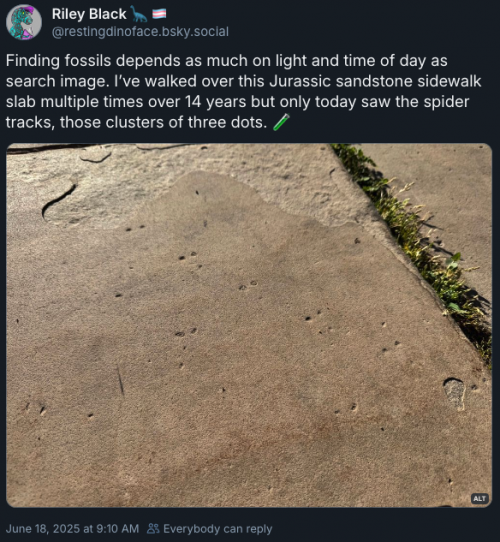

Finding fossils depends as much on light and time of day as search image. I’ve walked over this Jurassic sandstone sidewalk slab multiple times over 14 years but only today saw the spider tracks, those clusters of three dots. 🧪

I need to know how many tons a Jurassic spider weighed.