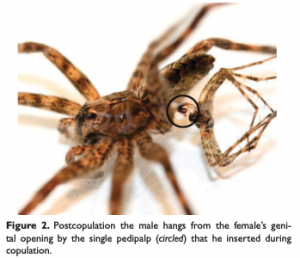

I’m learning things from raising Steatoda triangulosa. Feeding time is a marvel: I recorded a very short video of the little spiderlings’ reaction to having a fruit fly thrown at them. It’s like instant implacable carnivory! They’re eager to leap onto their prey, exhibiting the same behaviors as the adults.

So, this is my idea of a good parenting book. Take your little human baby, and toss a small calf or a large puppy into the crib with him or her. Leave them to their business for a few days. Come back later and remove the bones and scraps, and toss them another one. Repeat until they’re old enough to hunt on their own.

I guess since they’re weak humans, you could give the baby a Bowie knife or something to compensate.

Unfortunately, my own children are all growed up, and it’s too late to try on them. My kids probably won’t let me try this with the grandkids. That means…