There has been an ongoing and ugly legal battle over rights to the CRISPR/Cas technology for gene editing, which has swiftly become an important tool in the molecular biology toolbox. I think most of us agree that the people most responsible for the discovery are Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, but then the Broad Institute under Eric Lander saw a hot topic, threw bodies at the problem, and rushed to get their fingers in the pie, including, as a sneaky tactic, publishing a review article that downplayed the role of Doudna/Charpentier. It was a nasty, greedy game they were playing, and I’d hoped people would see through it.

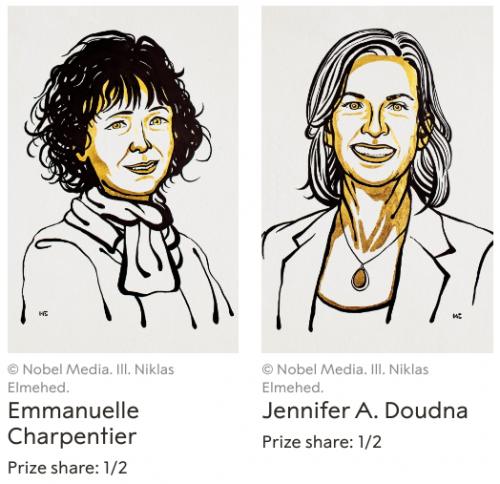

Apparently they did, because now Doudna and Charpentier have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Justice served!

It’s clear now that history has stamped Doudna and Charpentier with the credit for this scientific discovery, which is nice. I doubt that that will matter much to the legal system which determines who gets stamped with all the money from the patents, but it is a step forward.