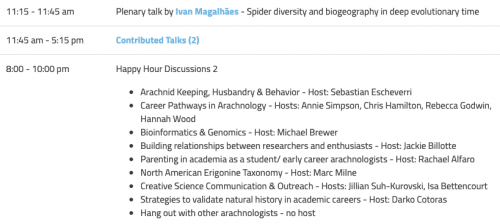

At least, I’m pretty sure.

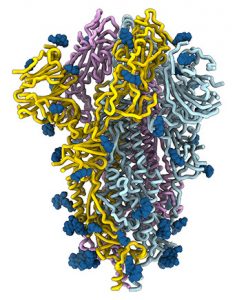

That’s Homo longi, or Dragon Man, a recently rediscovered fossil from China. It has a curious history.

Almost 90 years ago, Japanese soldiers occupying northern China forced a Chinese man to help build a bridge across the Songhua River in Harbin. While his supervisors weren’t looking, he found a treasure: a remarkably complete human skull buried in the riverbank. He wrapped up the heavy cranium and hid it in a well to prevent his Japanese supervisors from finding it. Today, the skull is finally coming out of hiding, and it has a new name: Dragon Man, the newest member of the human family, who lived more than 146,000 years ago.

Here, take a tour of the skull with Chris Stringer:

That is a big head-bone! The most provocative idea about it is that it might be one of the mysterious Denisovans, known only from DNA and fragmentary teeth.

I’ve been so deeply steeped in spider lore lately, though, that my perspective has shifted to finding it hard to believe in species anymore anyway. It’s cool to see that humans were also a diverse clade with subtle variants 150,000 years ago, almost as messy and complicated as, say, the Tetragnatha.